Reasons to Learn About Child Development

For us, as both parents and researchers, the sheer enjoyment of watching children and trying to understand them is reason enough for studying child development. What could be more fascinating than the development of a child? But there are also practical and intellectual reasons for studying child development. Understanding how children develop can improve child-rearing, promote the adoption of wiser social policies regarding children’s welfare, and answer intriguing questions about human nature. We examine each of these reasons in the following sections.

Raising Children

Being a good parent is not easy. Among its many challenges are the endless questions it raises over the years. Is it okay to take my infant outside in the cold weather? Should my baby stay at home, or would going to day care be better for his social development? If my daughter starts walking and talking early, should I consider placing her in a school for gifted children? Should I try to teach my 3-year-old to read early? My son seems so lonely at preschool; how can I help him make friends? How can I help my kindergartner deal with her anger?

Child-development research can help answer such questions. For example, one problem that confronts almost all parents is how to help their children control their anger and other negative emotions. One tempting, and frequent, reaction is to spank children who express anger in inappropriate ways, such as fighting, name-calling, and talking back. In a study involving a representative U.S. sample, 80% of parents of kindergarten children reported having spanked their child on occasion, and 27% reported having spanked their child the previous week (Gershoff et al., 2012). In fact, spanking made the problem worse. The more often parents spanked their kindergartners, the more often the same children argued, fought, and acted inappropriately at school when they were 3rd-graders. This relation held true for Blacks, Whites, Hispanics, and Asians alike, and it held true above and beyond the effects of other relevant factors, such as parents’ income and education.

Fortunately, research suggests several effective alternatives to spanking (Denham, 1998, 2006). One is expressing sympathy: when parents respond to their children’s distress with sympathy, the children are better able to cope with the situation causing the distress. Another effective approach is helping angry children find positive alternatives to expressing anger. For example, encouraging them to do something they enjoy helps them cope with the hostile feelings.

4

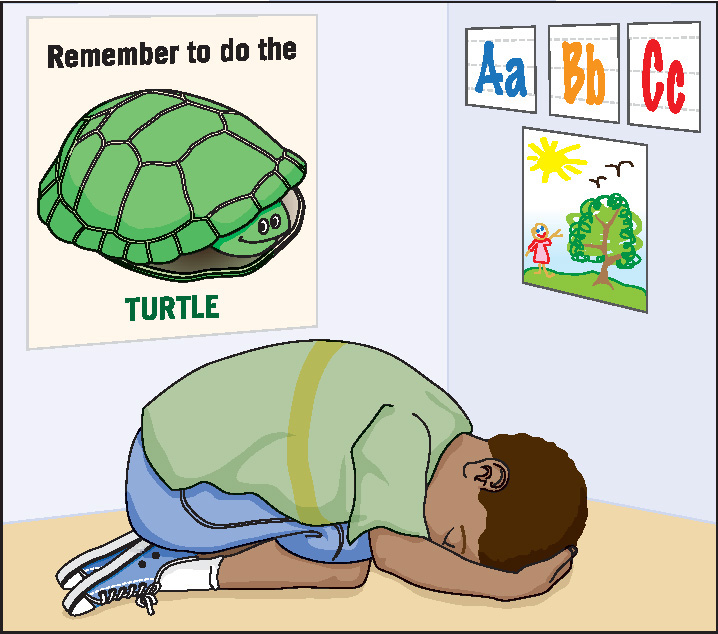

These strategies and similar ones, such as time-outs, can also be used effectively by others who contribute to raising children, such as day-care personnel and teachers. One demonstration of this was provided by a special curriculum that was devised for helping preschoolers (3- and 4-year-olds) who were angry and out of control (Denham & Burton, 1996). With this curriculum, preschool teachers helped children recognize their own and other children’s emotions, taught them techniques for controlling their anger, and guided them in resolving conflicts with other children. One approach that children were taught for coping with anger was the “turtle technique.” When children felt themselves becoming angry, they were to move away from other children and retreat into their “turtle shell,” where they could think through the situation until they were ready to emerge from the shell. Posters were placed around the classroom to remind children of what to do when they became angry.

The curriculum was quite successful. Children who participated in it became more skillful in recognizing and regulating anger when they experienced it and were generally less negative. For example, one boy, who had regularly gotten into fights when angry, told the teacher after a dispute with another child, “See, I used my words, not my hands” (Denham, 1998, p. 219). The benefits of this program can be long-term. In one test conducted with children in special education classrooms, positive effects were still evident 2 years after children completed the curriculum (Greenberg & Kusché, 2006). As this example suggests, knowledge of child-development research can be helpful to everyone involved in the care of children.

Choosing Social Policies

Another reason to learn about child development is to be able to make informed decisions not just about one’s own children but also about a wide variety of social-policy questions that affect children in general. For example, how much trust should judges and juries place in preschoolers’ testimony in child-abuse cases? Should children who do poorly in school be held back, or should they be promoted to the next grade so that they can be with children of the same age? How effective are health-education courses aimed at reducing teenage smoking, drinking, and pregnancy? Child-development research can inform discussion of all of these policy decisions and many others.

Consider the issue of how much trust to put in preschoolers’ courtroom testimony. At present, more than 100,000 children testify in legal cases each year (Bruck, Ceci, & Principe, 2006). Many of these children are very young: more than 40% of children who testify in sexual-abuse trials, for example, are younger than 5 years, and almost 40% of substantiated sexual-abuse cases involve children younger than age 7 (Bruck et al., 2006; Gray, 1993). The stakes are extremely high in such cases. If juries believe children who falsely testify that they were abused, innocent people may spend years in jail. If juries do not believe children who accurately report abuse, the perpetrators will go free and probably abuse other children. So what can be done to promote reliable testimony from young children and to avoid leading them to report experiences that never occurred?

5

Psychological research has helped answer such questions. In one experiment, researchers tested whether biased questioning affects the accuracy of young children’s memory for events involving touching one’s own and other people’s bodies. The researchers began by having 3- to 6-year-olds play a game, similar to “Simon Says,” in which the children were told to touch various parts of their body and those of other children. A month later, the researchers had a social worker interview the children about their experiences during the game (Ceci & Bruck, 1998). Before the social worker conducted the interviews, she was given a description of each child’s experiences. Unknown to her, the description included inaccurate as well as accurate information. For example, she might have been told that a particular child had touched her own stomach and another child’s nose, when in fact the child had touched her own stomach and the other child’s foot. After receiving the description, the social worker was given instructions much like those in a court case: “Find out what the child remembers.”

As it turned out, the version of events that the social worker had heard often influenced her questions. If, for example, a child’s account of an event was contrary to what the social worker believed to be the case, she tended to question the child repeatedly about the event (“Are you sure you touched his foot? Is it possible you touched some other part of his body?”). Faced with such repeated questioning, children fairly often changed their responses, with 34% of 3- and 4-year-olds eventually corroborating at least one of the social worker’s incorrect beliefs. Children were led to “remember” not only plausible events that never happened but also unlikely ones that the social worker had been told about. For example, some children “recalled” their knee being licked and a marble being inserted in their ear.

Studies such as this have yielded a number of conclusions regarding children’s testimony in legal proceedings. One important finding is that when 3- to 5-year-olds are not asked leading questions, their testimony is usually accurate, as far as it goes (Bruck et al., 2006; Howe & Courage, 1997). However, when prompted by leading questions, young children’s testimony is often inaccurate, especially when the leading questions are asked repeatedly. The younger children are, the more susceptible they are to being led, and the more their recall reflects the biases of the interviewer’s questions. In addition, realistic props, such as anatomically correct dolls and drawings, that are often used in judicial cases in the hopes of improving recall of sexual abuse, do not improve recall of events that occurred; they actually increase the number of inaccurate claims, perhaps by blurring the line between fantasy play and reality (Lamb et al., 2008; Poole, Bruck, & Pipe, 2011). Research on child eyewitness testimony has had a large practical impact, leading many judicial and police agencies to revise their procedures for interviewing child witnesses to incorporate the lessons of this research (e.g., State of Michigan, Governor’s Task Force, 2005). In addition to helping courts obtain more accurate testimony from young children, such research-based conclusions illustrate how, at a broader level, knowledge of child development can inform social policies.

6

Understanding Human Nature

A third reason to study child development is to better understand human nature. Many of the most intriguing questions regarding human nature concern children. For example, does learning start only after children are born, or can it occur in the womb? Can later upbringing in a loving home overcome the detrimental effects of early rearing in a loveless institutional setting? Do children vary in personality and intellect from the day they are born, or are they similar at birth, with differences arising only because they have different experiences? Until recently, people could only speculate about the answers to such questions. Now, however, developmental scientists have methods that enable them to observe, describe, and explain the process of development.

A particularly poignant illustration of the way in which scientific research can increase understanding of human nature comes from studies of how children’s ability to overcome the effects of early maltreatment is affected by its timing, that is, the age at which the maltreatment occurs. One such research program has examined children whose early life was spent in horribly inadequate orphanages in Romania in the late 1980s and early 1990s (McCall et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2007; Rutter et al., 2004). Children in these orphanages had almost no contact with any caregiver. For reasons that remain unknown, the brutal Communist dictatorship of that era instructed staff workers not to interact with the children, even when giving them their bottles. Staff members provided the infants with so little physical contact that the crown of many infants’ heads became flattened from the babies’ lying on their backs for 18 to 20 hours per day.

Shortly after the collapse of Communist rule in Romania, a number of these children were adopted by families in Great Britain. When these children arrived in Britain, most were severely malnourished, with more than half being in the lowest 3% of children their age in terms of height, weight, and head circumference. Most also showed varying degrees of mental retardation and were socially immature. The parents who adopted them knew of their deprived backgrounds and were highly motivated to provide loving homes that would help the children overcome the damaging effects of their early mistreatment.

To evaluate the long-term effects of their early deprivation, the physical, intellectual, and social development of about 150 of the Romanian-born children was examined at age 6 years. To provide a basis of comparison, the researchers also followed the development of a group of British-born children who had been adopted into British families before they were 6 months of age. Simply put, the question was whether human nature is sufficiently flexible that the Romanian-born children could overcome the extreme deprivation of their early experience, and if so, would that flexibility decrease with the children’s age and the length of the deprivation.

By age 6, the physical development of the Romanian-born children had improved considerably, both in absolute terms and in relation to the British-born comparison group. However, the Romanian children’s early experience of deprivation continued to influence their development, with the extent of negative effects depending on how long the children had been institutionalized. Romanian-born children who were adopted by British families before age 6 months, and who had therefore spent the smallest portion of their early lives in the orphanages, weighed about the same as British-born children when both were 6-year-olds. Romanian-born children adopted between the ages of 6 and 24 months, and who therefore had spent more of their early lives in the orphanages, weighed less; and those adopted between the ages of 24 and 42 months weighed even less (Rutter et al., 2004).

7

Intellectual development at age 6 years showed a similar pattern. The Romanian-born children who had been adopted before age 6 months demonstrated levels of intellectual competence comparable with those of the British-born group. Those who had been adopted between ages 6 and 24 months did somewhat less well, and those adopted between ages 24 and 42 months did even more poorly (Rutter et al., 2004). The intellectual deficits of the Romanian children adopted after age 6 months were just as great when the children were retested at age 11, indicating that the negative effects of the early deprivation persisted over time (Beckett et al., 2006; Kreppner et al., 2007).

The early experience in the orphanages had similar damaging effects on the children’s social development (Kreppner et al., 2007; O’Connor, Rutter, & English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, 2000). Almost 20% of the Romanian-born children who were adopted after age 6 months showed extremely abnormal social behavior at age 6 years, not looking at their parents in anxiety-provoking situations and willingly going off with strangers (versus 3% of the British-born comparison group who did so). This atypical social development was accompanied by abnormal brain activity. Brain scans obtained when the children were 8 years old showed that those adopted after living for a substantial period in the orphanages had unusually low levels of neural activity in the amygdala, a brain area involved in emotional reactions (Chugani et al., 2001). Subsequent studies have identified similar brain abnormalities among children who spent their early lives in poor-quality orphanages in Russia and East Asia as well (Nelson et al., 2011; Tottenham et al., 2010).

These findings reflect a basic principle of child development that is relevant to many aspects of human nature: The timing of experiences influences their effects. In the present case, children were sufficiently flexible to overcome the effects of living in the loveless, unstimulating institutions if the deprivation ended relatively early; living in the institutions until older ages, however, had effects that were rarely overcome, even when children spent subsequent years in loving and stimulating environments. The adoptive families clearly made a huge positive difference in their children’s lives, but the later the age of adoption, the greater the long-term effects of early deprivation.

review:

There are at least three good reasons to learn about child development: to improve one’s own child-rearing, to help society promote the well-being of children in general, and to better understand human nature.