84

Biology and Behavior

85

- Nature and Nurture

- Genetic and Environmental Forces

- Box 3.1: Applications Genetic Transmission of Disorders

- Behavior Genetics

- Box 3.2: Individual Differences Identical Twins Reared Apart

- Review

- Genetic and Environmental Forces

- Brain Development

- Structures of the Brain

- Developmental Processes

- Box 3.3: A Closer Look Mapping the Mind

- The Importance of Experience

- Brain Damage and Recovery

- Review

- The Body: Physical Growth and Development

- Growth and Maturation

- Nutritional Behavior

- Review

- Chapter Summary

86

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

Continuity/Discontinuity

Continuity/Discontinuity

Mechanisms of Change

Mechanisms of Change

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

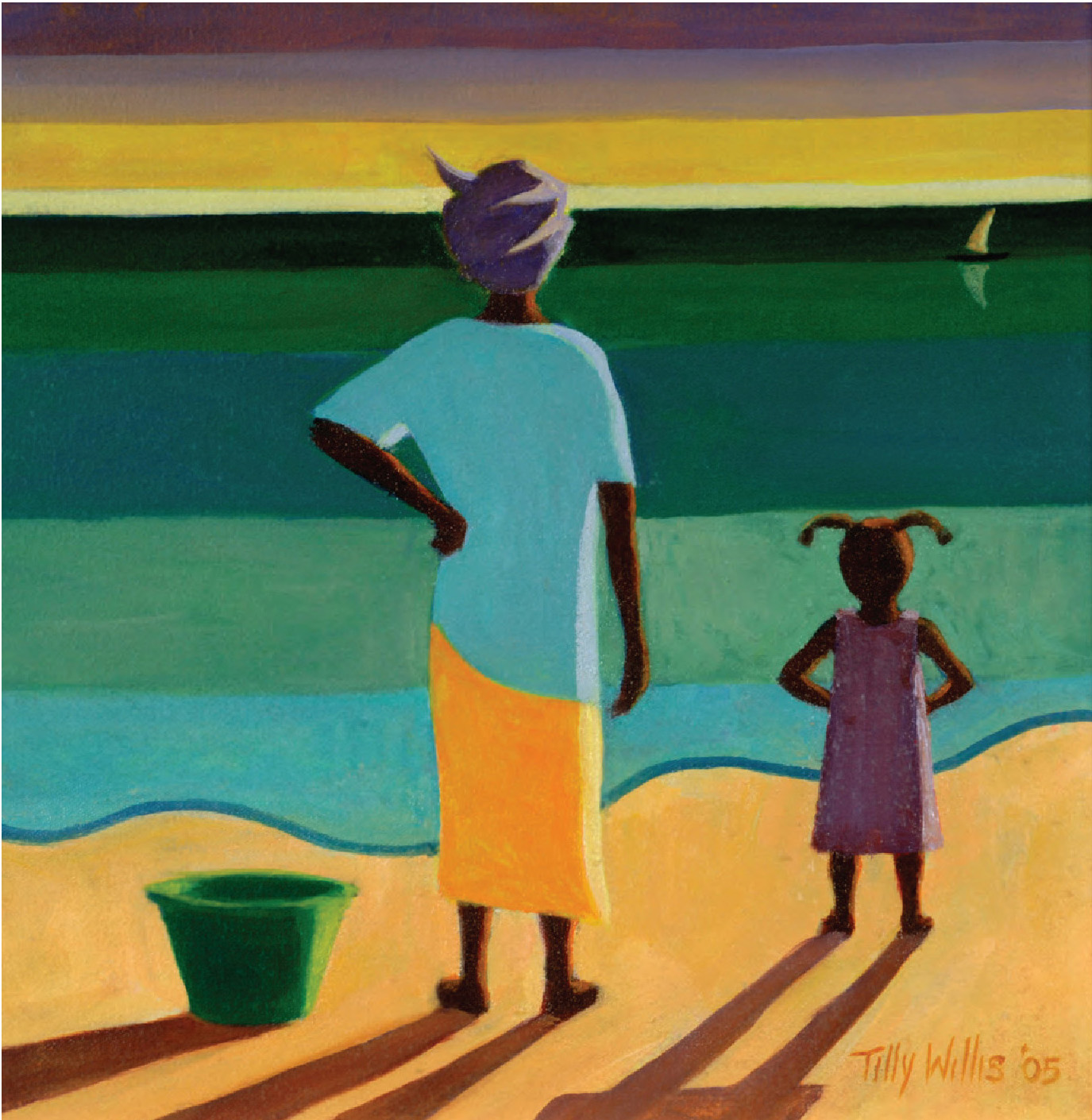

everal years ago, one of your authors received a call from the police. A city detective wanted to come by for a chat about some street and traffic signs that had been stolen—and also about the fact that one of the culprits was the author’s 17-year-old son. In an evening of hilarious fun and poor judgment, the son, along with two friends, had stolen more than a dozen city signs and then concealed them in the family attic. His upset parents wondered how their sweet, sensitive, kind, soon-to-be Eagle Scout son (who can be seen in his innocent days) could have failed to foresee the consequences of his actions.

everal years ago, one of your authors received a call from the police. A city detective wanted to come by for a chat about some street and traffic signs that had been stolen—and also about the fact that one of the culprits was the author’s 17-year-old son. In an evening of hilarious fun and poor judgment, the son, along with two friends, had stolen more than a dozen city signs and then concealed them in the family attic. His upset parents wondered how their sweet, sensitive, kind, soon-to-be Eagle Scout son (who can be seen in his innocent days) could have failed to foresee the consequences of his actions.

Many parents have similarly wondered how their once-model children could have morphed into thoughtless, irresponsible, self-absorbed, impolite, bad-tempered individuals simply by virtue of entering adolescence. Parents are not the only ones surprised by the change in the behavior of their offspring: teenagers themselves are often taken aback and mystified as to what has come over them. One 14-year-old girl lamented: “Sometimes, I just get overwhelmed now…. There’s all this friend stuff and school and how I look and my parents. I just go in my room and shut the door…. I don’t mean to be mean, but sometimes I just have to go away and calm down by myself.” And a 15-year-old boy expressed similar concerns: “I get in trouble a lot more now, but it’s for stuff I really didn’t mean…. I forget to call home. I don’t know why. I just hang out with friends, and I get involved with that and I forget. Then my parents get really mad, and then I get really mad, and it’s a big mess” (Strauch, 2003).

New insights into these often abrupt developmental changes have come through research into the biological underpinnings of behavioral development. Researchers now suspect that many of the behavioral changes that are distressing both to adolescents and their parents may be related to dramatic changes in brain structure and functioning that occur during adolescence. In addition, there is growing evidence that some genetic predispositions do not emerge until adolescence and that they may contribute to these seemingly abrupt developmental changes.

Understanding the biological underpinnings of behavioral development is, of course, essential to understanding development at any point in the life span. The focus of this chapter is on the key biological factors that are in play from the moment of conception through adolescence, including the inheritance and influence of genes, the development and early functioning of the brain, and important aspects of physical development and maturation. Every cell in our bodies carries the genetic material that we inherited at our conception and that continues to influence our behavior throughout life. Every behavior we engage in is directed by our brain. Everything we do at every age is mediated by a constantly changing physical body—one that changes very rapidly and dramatically in the first few years of life and in adolescence, but more slowly and subtly at other times.

Several of the themes that were set out in Chapter 1 figure prominently in this chapter. Issues of nature and nurture, as well as individual differences among children, are central throughout this whole chapter and especially the first section, which focuses on the interaction of genetic and environmental factors in development. Mechanisms of change are prominent in our discussions of the developmental role of genetic factors and of the processes involved in the relationship between brain functioning and behavior. Continuity in development is also highlighted throughout the chapter. We again emphasize the activity-dependent nature of developmental processes and the role of the active child in charting the course of his or her own development.

87