Nonlinguistic Symbols and Development

Although language is our preeminent symbol system, humans have invented a wealth of other kinds of symbols to communicate with one another. Virtually anything can serve as a symbol so long as someone intends it to stand for something other than itself (DeLoache, 2002, 2004). The list of symbols you regularly encounter is long and varied, ranging from the printed words, numbers, graphs, photographs, and drawings in your textbooks to thousands of everyday items such as computer icons, maps, clocks, and so on. Because symbols are so central to our everyday lives, mastering the symbol systems important in their culture is a crucial developmental task for all children.

Symbolic proficiency involves both the mastery of the symbolic creations of others and the creation of new symbolic representations. We will first discuss early symbolic functioning, starting with research on very young children’s ability to exploit the informational content of symbolic artifacts. Then we will focus on children’s creation of symbols through drawing. In Chapter 7, we will consider children’s creation of symbolic relations in pretend play, and in Chapter 8, we will examine older children’s development of two of the most important of all symbolic activities—reading and mathematics.

253

Using Symbols as Information

dual representation  the idea that a symbolic artifact must be represented mentally in two ways at the same time—both as a real object and as a symbol for something other than itself

the idea that a symbolic artifact must be represented mentally in two ways at the same time—both as a real object and as a symbol for something other than itself

One of the vital functions of many symbols is that they provide useful information. For example, a map—whether a crude pencil sketch on the back of an envelope or a Google map on your smartphone—can be crucial for locating a particular place. To use a symbolic artifact such as a map requires dual representation; that is, the artifact must be represented mentally in two ways at the same time, as a real object and as a symbol for something other than itself (DeLoache, 2002, 2004).

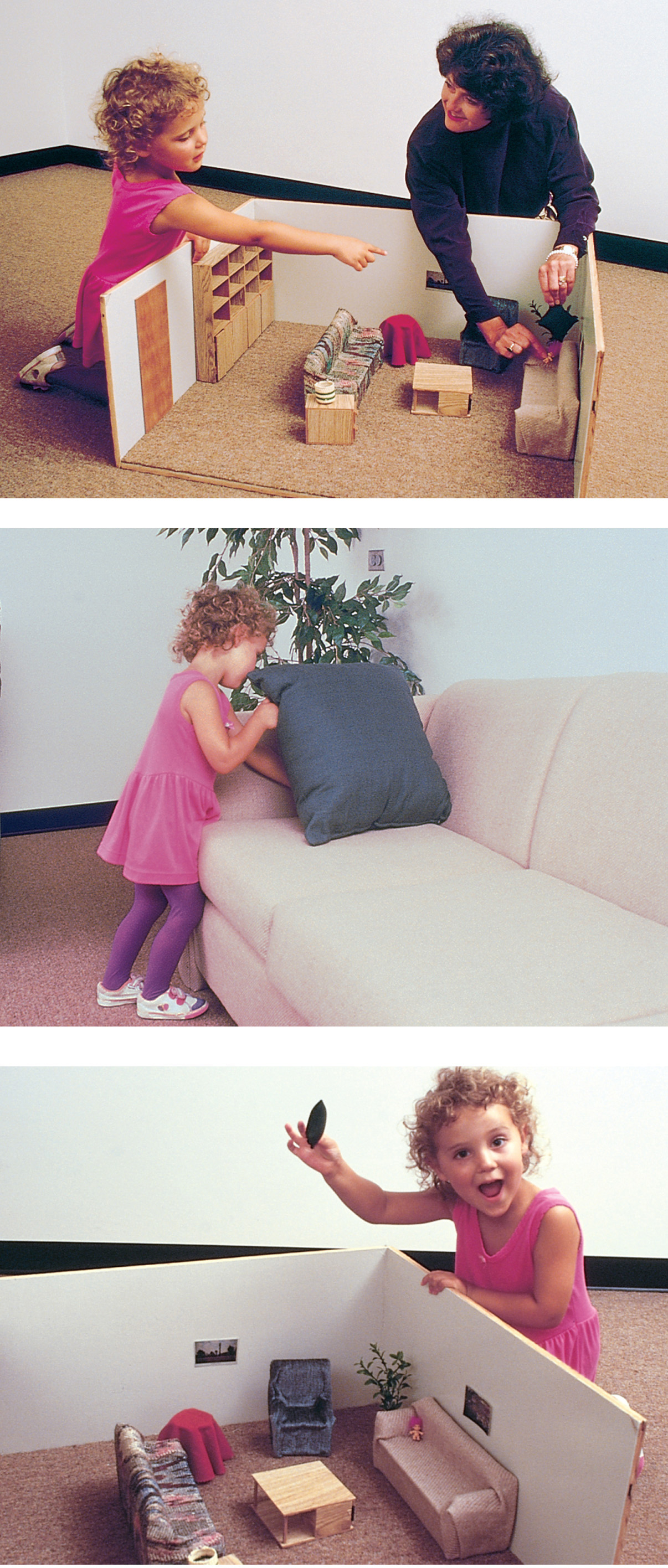

Very young children have substantial difficulty with dual representation, limiting their ability to use information from symbolic artifacts (DeLoache, 2004). This has been demonstrated by research in which a young child watches as an experimenter hides a miniature toy in a scale model of the regular-sized room next door (Figure 6.13) (DeLoache, 1987). The child is then asked to find a larger version of the toy that the child is told “is hiding in the same place in the big room.” Three-year-olds readily use their knowledge of the location of the miniature toy in the model to figure out where the large toy is in the adjacent room. In contrast, most 2½-year-old children fail to find the large toy; they seem to have no idea that the model tells them anything about the full-size room. Because the model is so salient and interesting as a three-dimensional object, very young children have trouble managing dual representation and fail to notice the symbolic relation between the model and the room it stands for.

This interpretation received strong support in a study with 2½-year-old children in which reasoning between a model and a larger space was not necessary (DeLoache, Miller, & Rosengren, 1997). An experimenter showed each child a “shrinking machine” (really an oscilloscope with lots of dials and lights) and explained that the machine could “make things get little.” The child watched as a troll doll was hidden in a movable tentlike room (approximately 8 feet by 6 feet) and the shrinking machine was “turned on.” Then the child and experimenter waited in another room while the shrinking machine did its job. When they returned, a small-scale model of the tentlike room stood in place of the original. (Assistants had, of course, removed the original tent and replaced it with the scale model.) When asked to find the troll, the children succeeded.

Why should the idea of a shrinking machine enable these 2½-year-olds to perform the task? The answer is that if a child believes the experimenter’s claims about the shrinking machine, then in the child’s mind the model simply is the room. Hence, there is no symbolic relation between the two spaces and no need for dual representation.

The difficulty that young children have with dual representation and symbols is evident in other contexts as well. For example, investigators often use anatomically detailed dolls to interview young children in cases of suspected sexual abuse, assuming that the relation between the doll and themselves would be obvious. However, children younger than 5 years often fail to make any connection between themselves and the doll, so the use of a doll does not improve their memory reports and may even make them less reliable (Bruck et al., 1995; DeLoache & Marzolf, 1995; Goodman & Aman, 1990).

254

Increasing ability to achieve dual representation—to immediately interpret a symbol in terms of what it stands for—enables children to discover the abstract nature of various symbolic artifacts. For example, unlike younger children, school-aged children realize that the red line on a road map does not mean that the real road would be red (Liben & Myers, 2007). Older children are also able, when properly instructed, to use objects such as rods and blocks of different sizes that represent different numerical quantities to help them learn to do mathematical operations (Uttal, Liu, & DeLoache, 2006).

Drawing

Creating pictures is a common symbolic activity encouraged by parents in many societies (Goodnow, 1977). When young children first start making marks on paper, their focus is almost exclusively on the activity per se, with no attempt to produce recognizable images. At around 3 or 4 years or age, most children begin trying to draw pictures of something; they try to produce representational art (Callaghan, 1999). Exposure to representational symbols affects the age at which children begin to produce them. One recent study (Callaghan et al., 2011) found that children from homes filled with pictorial images (a Canadian sample) produce such images earlier and more often than children from homes with few such images (Indian and Peruvian samples).

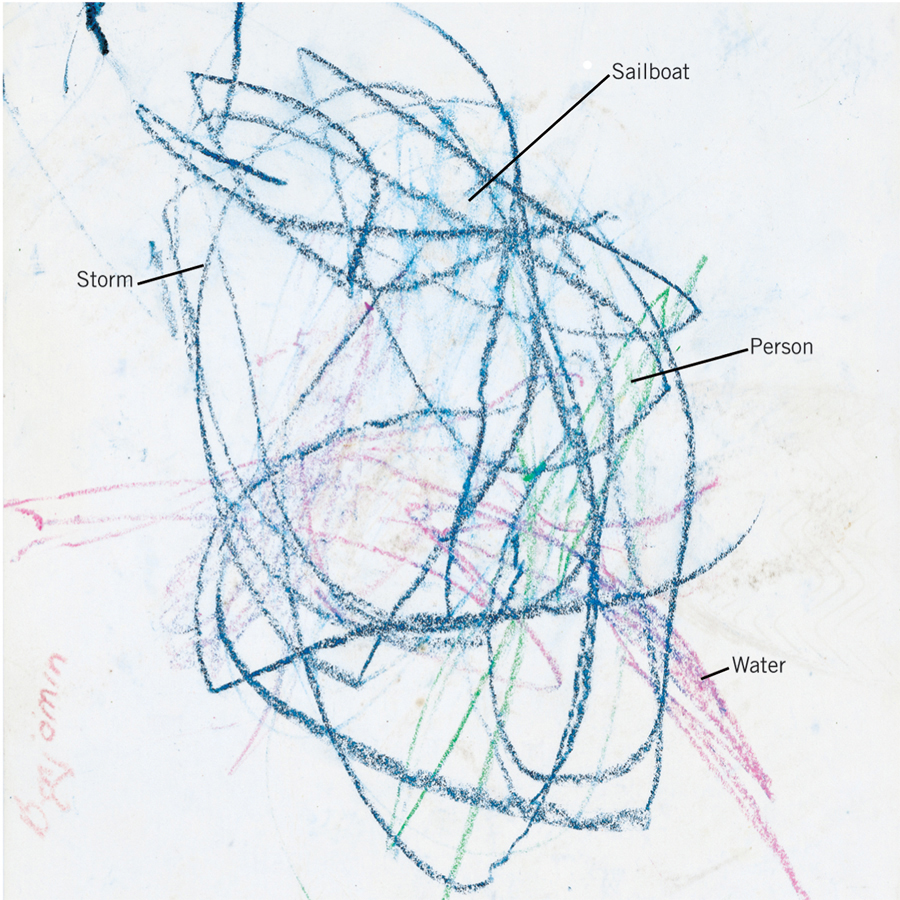

Initially, children’s artistic impulses outstrip their motor and planning capabilities (Yamagata, 1997). Figure 6.14 shows what at first appears simply to be a classic scribble. However, the 2½-year-old creator of this picture was narrating his efforts as he drew, making it possible to ascertain his artistic intentions. While he represented the individual elements of his picture reasonably well, he was unable to coordinate them spatially.

255

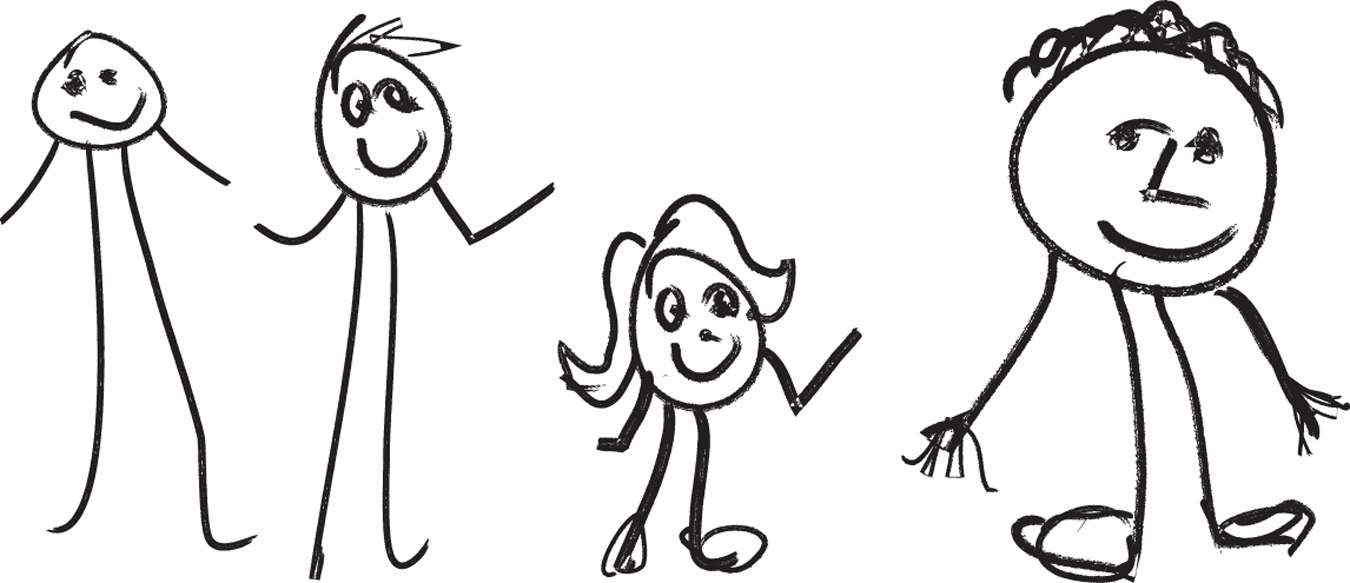

The most common subject for young children is the human figure (Goodnow, 1977). Just as infants who are first beginning to speak simplify the words they produce, young children simplify their drawings, as shown in Figure 6.15. Note that to produce these very simple, crude shapes, the child must plan the drawing and must spatially coordinate the individual elements. Even early “tadpole” people have the legs on the bottom and the arms on the side—although often emerging from the head.

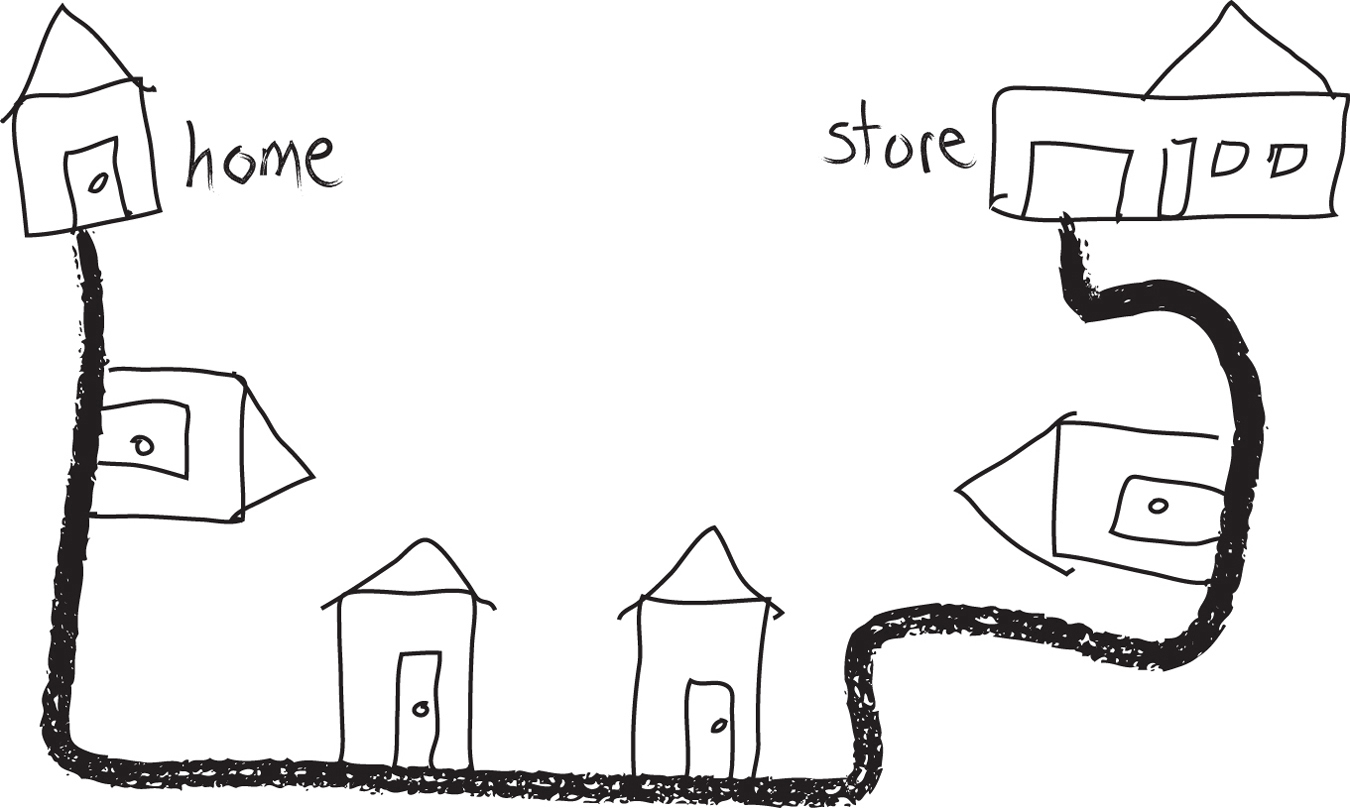

Figure 6.16 reveals some of the strategies children use to produce more complex pictures. The drawing depicts the route from the artist’s home to the local grocery store, with several houses along the way. One strategy the child used was to rely on a well-practiced formula for representing houses: a rectangle with a door and a roofline. Another was to coordinate the placement of each house with respect to the road, although at the cost of the overall coordination among the houses. Eventually, some children become highly skilled at representing the relations among the multiple elements in their pictures.

review:

Nonlinguistic symbols play an important role in the lives of young children. As they become increasingly sensitive to the informational potential of symbolic objects created by others, children take an important step toward skillful use of the many symbol systems that are key to modern life. A critical factor in understanding and using the symbols created by others is dual representation—the ability to mentally represent both a symbolic object, such as a map or model, and its relation to what it stands for. The ability to create symbols is evident in young children’s drawings.

256