What Is Intelligence?

Intelligence is notoriously difficult to define, but this has not kept people from trying. Part of the difficulty is that intelligence can legitimately be described at three levels of analysis: as one thing, as a few things, or as many things.

Intelligence as a Single Trait

g (general intelligence)  cognitive processes that influence the ability to think and learn on all intellectual tasks

cognitive processes that influence the ability to think and learn on all intellectual tasks

Some researchers view intelligence as a single trait that influences all aspects of cognitive functioning. Supporting this idea is the fact that performance on all intellectual tasks is positively correlated: children who do well on one tend to do well on others, too (Geary, 2005). These positive correlations occur even among dissimilar intellectual tasks—for example, remembering lists of numbers and folding pieces of paper to reproduce printed designs. Such omnipresent positive correlations have led to the hypothesis that each of us possesses a certain amount of g, or general intelligence, and that g influences our ability to think and learn on all intellectual tasks (A. R. Jensen, 1998; Spearman, 1927).

Numerous sources of evidence attest to the usefulness of viewing intelligence as a single trait. Measures of g, such as overall scores on intelligence tests, correlate positively with school grades and achievement test performance (Gottfredson, 2011). At the level of cognitive and brain mechanisms, g correlates with information-processing speed (Coyle et al., 2011; Deary, 2000), speed of neural transmission (Vernon et al., 2000), and brain volume (McDaniel, 2005). Measures of g also correlate strongly with people’s knowledge of subjects—such as medicine, law, art history, and the Bible—that are not taught in school (Lubinski & Humphreys, 1997). Such evidence supports the view of intelligence as a single trait that involves the ability to think and learn.

Intelligence as a Few Basic Abilities

fluid intelligence  ability to think on the spot to solve novel problems

ability to think on the spot to solve novel problems

There are also good arguments for viewing intelligence as more than a single general trait. The simplest such view holds that there are two types of intelligence: fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence (Cattell, 1987):

- Fluid intelligence involves the ability to think on the spot—for example, by drawing inferences and understanding relations between concepts that have not been encountered previously. It is closely related to adaptation to novel tasks, speed of information processing, working-memory functioning, and ability to control attention (C. Blair, 2006; Geary, 2005).

- Crystallized intelligence is factual knowledge about the world: knowledge of word meanings, state capitals, answers to arithmetic problems, and so on. It reflects long-term memory for prior experiences and is closely related to verbal ability.

crystallized intelligence

factual knowledge about the world

factual knowledge about the world

The distinction between fluid and crystallized intelligence is supported by the fact that tests of each type of intelligence correlate more highly with each other than they do with tests of the other type (J. L. Horn & McArdle, 2007). Thus, children who do well on one test of fluid intelligence tend to do well on other tests of fluid intelligence but not necessarily on tests of crystallized intelligence. In addition, the two types of intelligence have different developmental courses. Crystallized intelligence increases steadily from early in life to old age, whereas fluid intelligence peaks around age 20 and slowly declines thereafter (Salthouse, 2009). The brain areas most active in the two types of intelligence also differ: the prefrontal cortex usually is especially active on measures of fluid intelligence but tends to be much less active in measures of crystallized intelligence (C. Blair, 2006; Jung & Haier, 2007).

primary mental abilities  seven abilities proposed by Thurstone as crucial to intelligence

seven abilities proposed by Thurstone as crucial to intelligence

A somewhat more differentiated view of intelligence (Thurstone, 1938) proposes that the human intellect is composed of seven primary mental abilities: word fluency, verbal meaning, reasoning, spatial visualization, numbering, rote memory, and perceptual speed. The key evidence for the usefulness of dividing intelligence into these seven abilities is similar to that for the distinction between fluid and crystallized intelligence. Scores on various tests of a single ability tend to correlate more strongly with each other than do scores on tests of different abilities. For example, although both spatial visualization and perceptual speed are measures of fluid intelligence, children tend to perform more similarly on two tests of spatial visualization than they do on a test of spatial visualization and a test of perceptual speed. The trade-off between these two views of intelligence is between the simplicity of the crystallized/fluid distinction and the greater precision of the idea of seven primary mental abilities.

Intelligence as Numerous Processes

A third view envisions intelligence as comprising numerous, distinct processes. Information-processing analyses of how people solve intelligence test items and how they perform everyday intellectual tasks such as reading, writing, and arithmetic reveal that a great many processes are involved (e.g., Geary, 2005). These include remembering, perceiving, attending, comprehending, encoding, associating, generalizing, planning, reasoning, forming concepts, solving problems, generating and applying strategies, and so on. Viewing intelligence as “many processes” allows more precise specification of the mechanisms involved in intelligent behavior than do approaches that view it as “a single trait” or “several abilities.”

A Proposed Resolution

three-stratum theory of intelligence  Carroll’s model that places g at the top of the intelligence hierarchy, eight moderately general abilities in the middle, and many specific processes at the bottom

Carroll’s model that places g at the top of the intelligence hierarchy, eight moderately general abilities in the middle, and many specific processes at the bottom

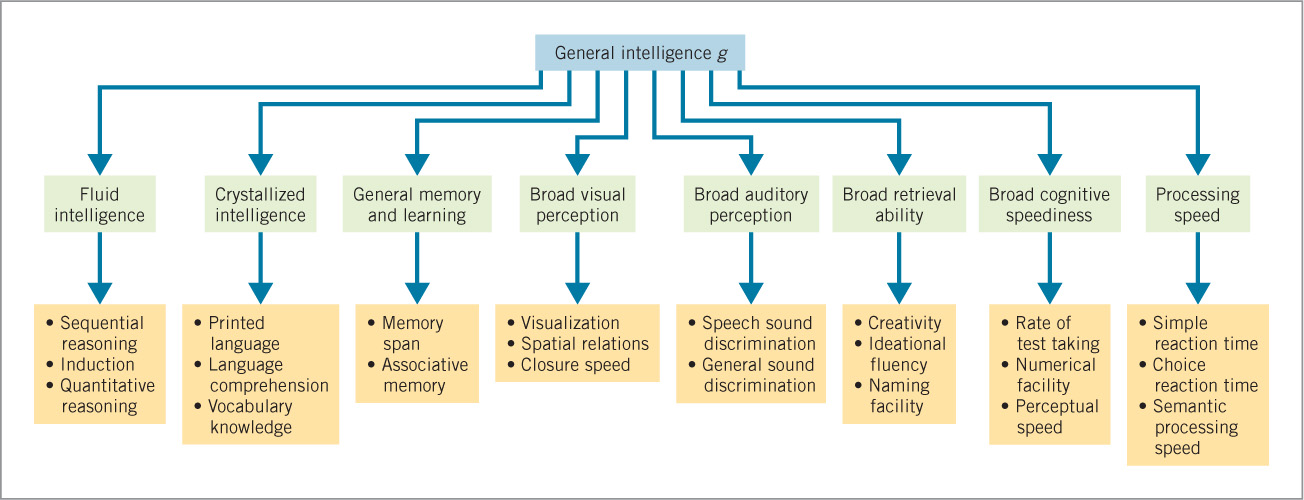

How can these competing perspectives on intelligence be reconciled? After studying intelligence for more than half a century, John B. Carroll (1993, 2005) proposed a grand integration: the three-stratum theory of intelligence (Figure 8.1). At the top of the hierarchy is g; in the middle are several moderately general abilities (which include both fluid and crystallized intelligence and other competencies similar to Thurstone’s seven primary mental abilities); at the bottom are many specific processes. General intelligence influences all moderately general abilities, and both general intelligence and the moderately general abilities influence the specific processes. For instance, knowing someone’s general intelligence allows for a fairly reliable prediction of the person’s general memory skills; knowing both of them allows quite reliable prediction of the person’s memory span; and knowing all three allows very accurate prediction of the person’s memory span for a particular type of material, such as words, letters, or numbers.

301

Carroll’s comprehensive analysis of the research literature indicated that all three levels of analysis that we have discussed in this section are necessary to account for the totality of facts about intelligence. Thus, for the question “Is intelligence a single trait, a few abilities, or many processes?” the correct answer seems to be “All of the above.”

review:

Intelligence can be viewed as a single general ability to think and learn; as several moderately general abilities, such as crystallized and fluid intelligence; or as a collection of numerous specific skills, processes, and content knowledge. All three levels are useful for understanding intelligence.