1-2 The stars are grouped by constellations

Go to Video 1-2

Go to Video 1-2

Looking at the sky on a clear, dark night, you might think that you can see millions of stars. Actually, the unaided human eye can detect only about 6000 stars. Because half of the sky is below the horizon at any one time, you can see at most about half of these stars. But how does one make sense of so many stars scattered about?

Stars Are Organized into Patterns Called Asterisms and the Sky is Divided into Sections Called Constellations

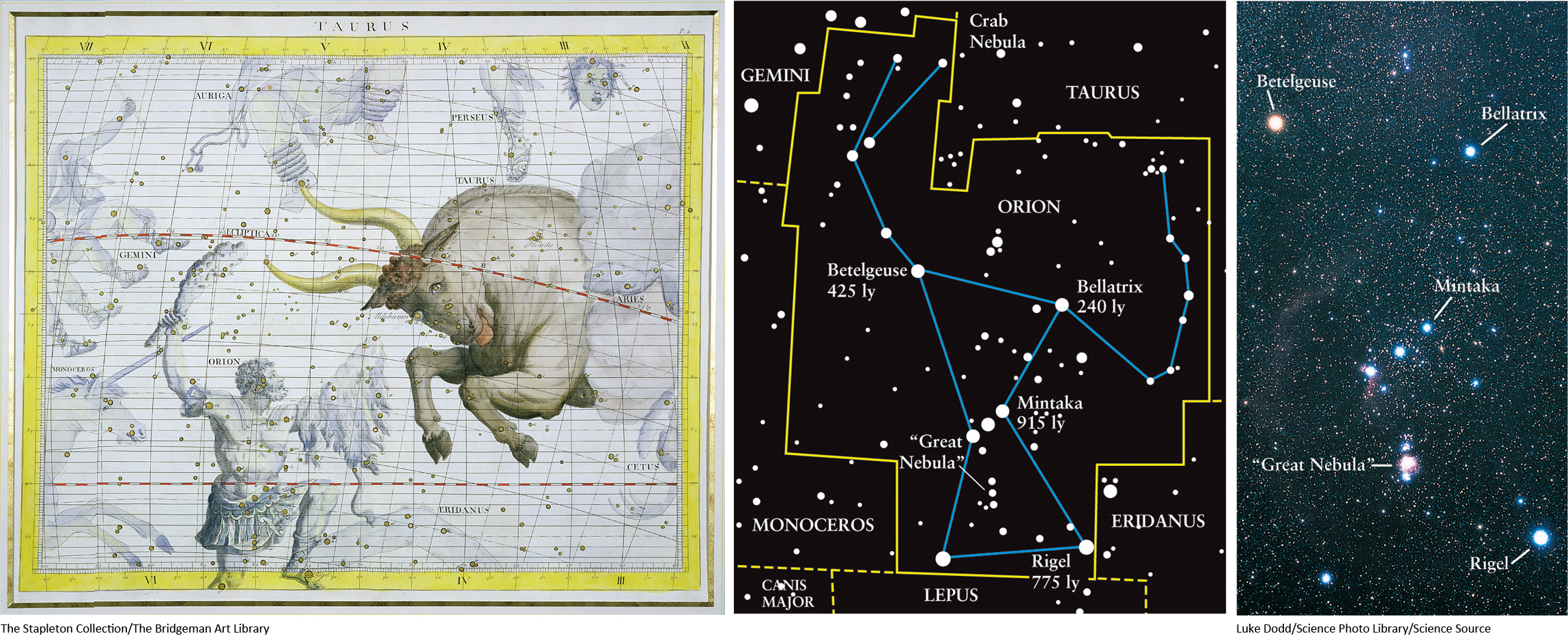

When ancient people looked at these thousands of stars, they imagined that groupings of stars traced out pictures in the sky, often by creating figures by connecting stars from dot to dot. These figures, which make somewhat recognizable shapes, are called asterisms. You may already be familiar with some of these pictures or patterns in the sky, such as the asterism of the Big Dipper. To make it easier to describe particular parts of the sky, today’s astronomers divide up the sky into semirectangular regions called constellations (from the Latin for “group of stars”). Many constellations, such as Orion in Figure 1-3, have names derived from the myths and legends of antiquity. Although some star groupings vaguely resemble the figures for which they are named (see Figure 1-3a), most do not. Constellations rarely, if ever, actually look like pictures of any kind.

6

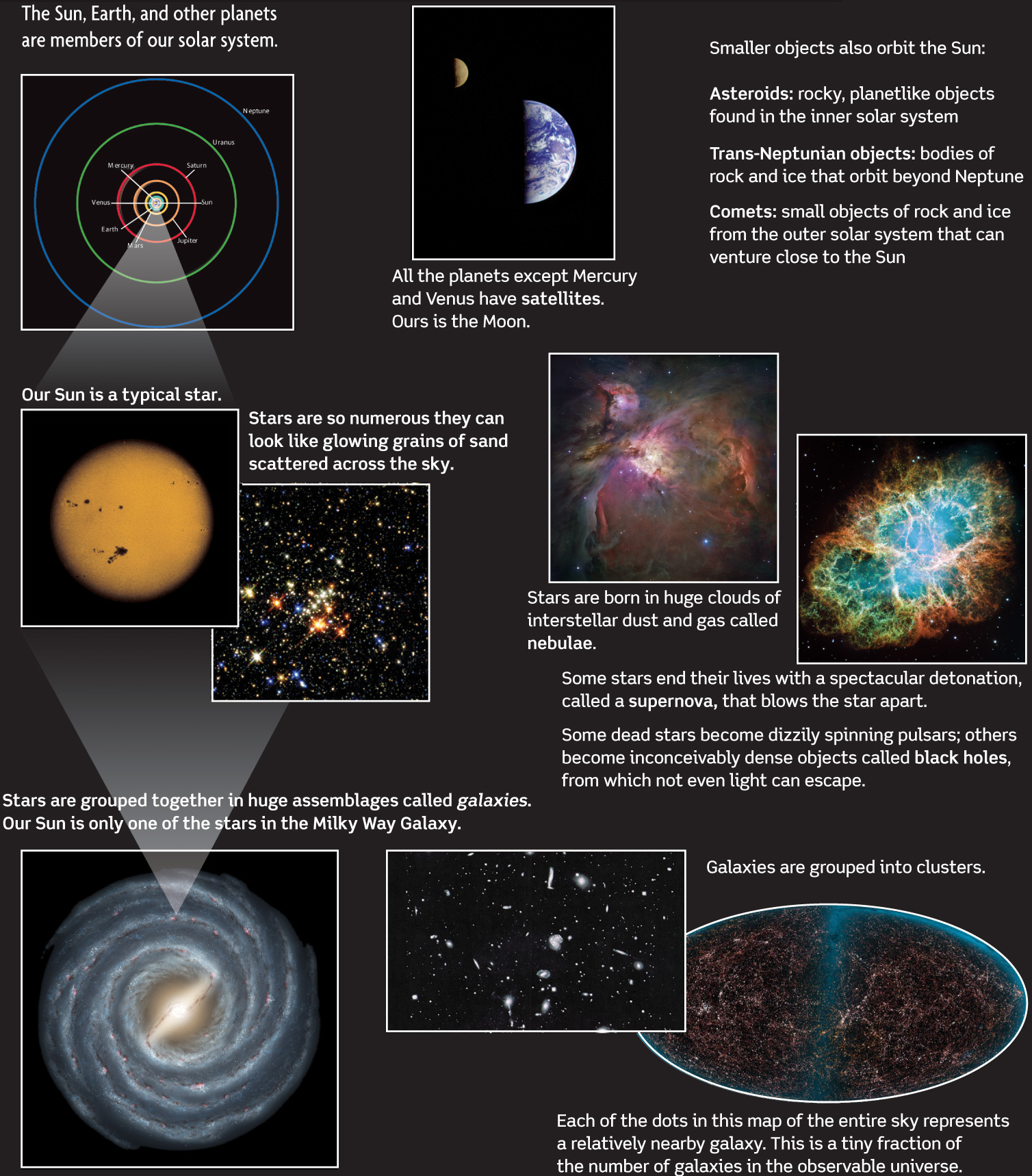

COSMIC CONNECTIONS Size and Structure of the Universe

7

The term “constellation” has a broader definition in present-day astronomy. On modern star charts, the entire sky is divided into 88 regions, each of which is called a constellation. For example, the constellation Orion is now defined to be an irregular patch of sky whose borders are shown in Figure 1-3b. When astronomers refer to the “Great Nebula” in Orion (see Figure 1-3c), they mean that as seen from Earth this nebula appears to be within Orion’s patch of sky. Some constellations cover large areas of the sky (Ursa Major being one of the biggest) and others very small areas (Crux, the Southern Cross, being the smallest). But because the modern constellations cover the entire sky, every star lies in one constellation or another.

When you look at a constellation’s star pattern, it is tempting to conclude that you are seeing a group of stars that are all relatively close together. In fact, most of these stars are nowhere near one another. As an example, in Figure 1-3b, although Bellatrix (Latin for “female warrior”) and Mintaka (Arabic for “the belt”) appear to be close to each other, Mintaka is actually farther away from us. The two stars only appear to be close because they are in nearly the same direction as seen from Earth. The same illusion often appears when you see an airliner’s lights at night. It is very difficult to tell how far away a single bright light is, which is why you can mistake an airliner a few kilometers away for a star trillions of times more distant.

Many of the star names shown in Figure 1-3b are drawn from the Arabic language. For example, Betelgeuse is sometimes translated as “armpit,” which makes sense when you look at the star atlas drawing in Figure 1-3a. Other types of names are also used for stars. For example, the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius, is also known as α Canis Major because it is also the brightest star in Canis Major (α, or alpha, is the first letter in the Greek alphabet).

CAUTION

A number of commercial firms offer to name a star for you for a fee. The money that they charge you for this “service” is real, but the star names are not; none of these names is recognized by professional astronomers. It can be a fun gift, but if you want to use astronomy to formally commemorate your name or the name of a friend or relative, consider making a donation to your local planetarium or science museum. The money will be put to much better use!

Constellations Are a Map in the Night Sky

Astronomers group the thousands of stars visible in the night sky into semirectangular regions called constellations and recognizable connect-the-dot shapes called asterisms.

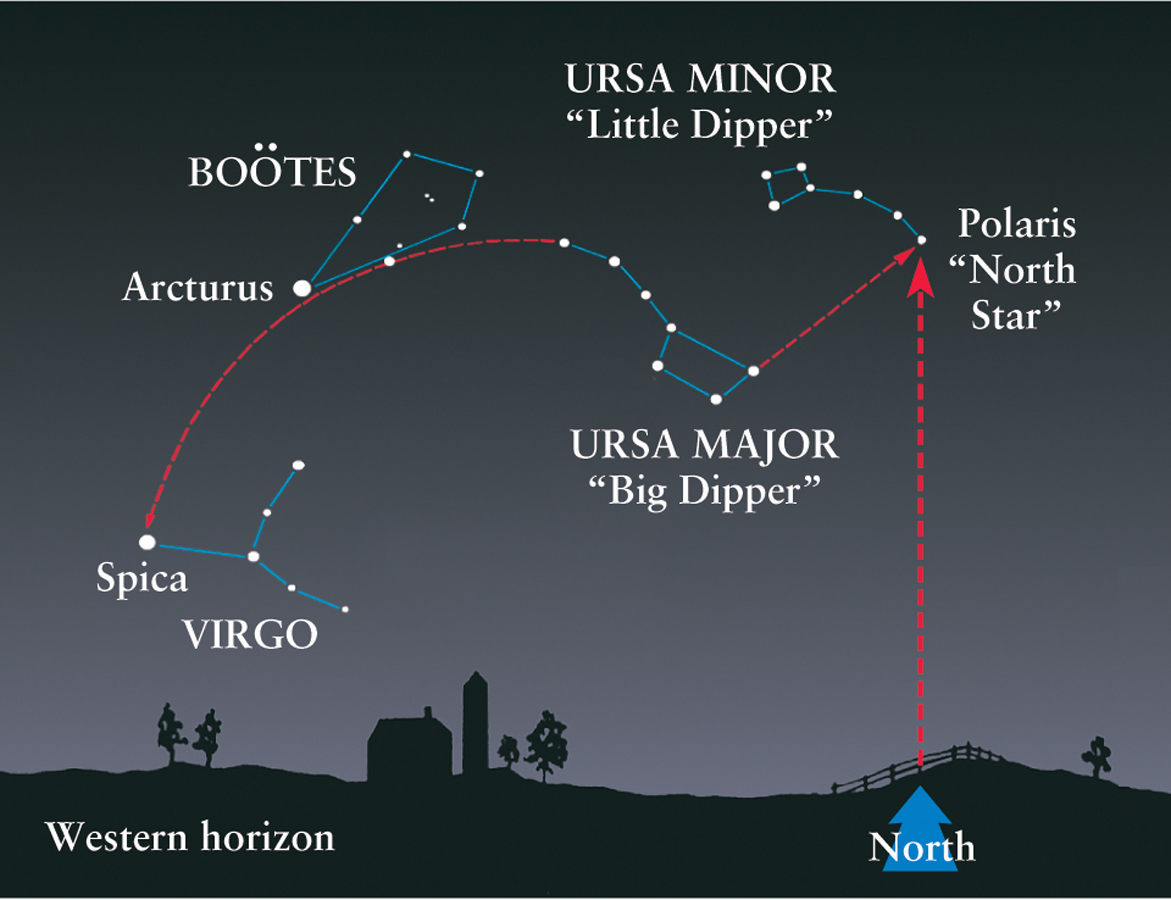

Easily recognizable groups of stars can help you find your way around the sky. For example, if you live in the northern hemisphere, you can use the asterism of the Big Dipper in the constellation of Ursa Major to find the north direction by drawing a straight line through the two stars at the front of the Big Dipper’s bowl (Figure 1-4). The first moderately bright star you come to is Polaris, also called the North Star because it is located almost directly over Earth’s north pole. If you draw a line from Polaris straight down to the horizon, you will find the north direction.

As Figure 1-4 shows, by following the handle of the Big Dipper you can locate the bright reddish star Arcturus in Boötes (the Shepherd) and the prominent bluish star Spica in Virgo (the Virgin). The saying “Follow the arc to Arcturus and speed on to Spica” may help you remember these stars, which are conspicuous in the evening sky during the spring and summer.

8

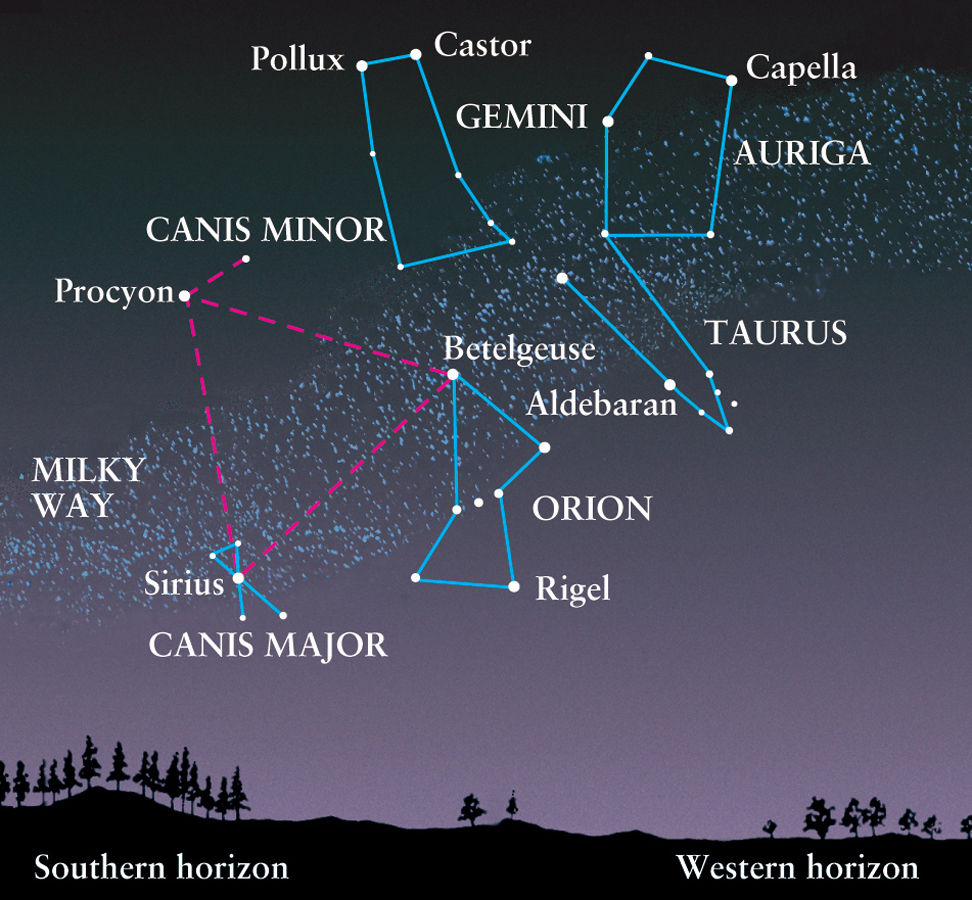

During winter in the northern hemisphere, you can see some of the brightest stars in the sky. Many of them are in the vicinity of the “winter triangle” (Figure 1-5), which connects bright stars in the constellations of Orion (the Hunter), Canis Major (the Large Dog), and Canis Minor (the Small Dog).

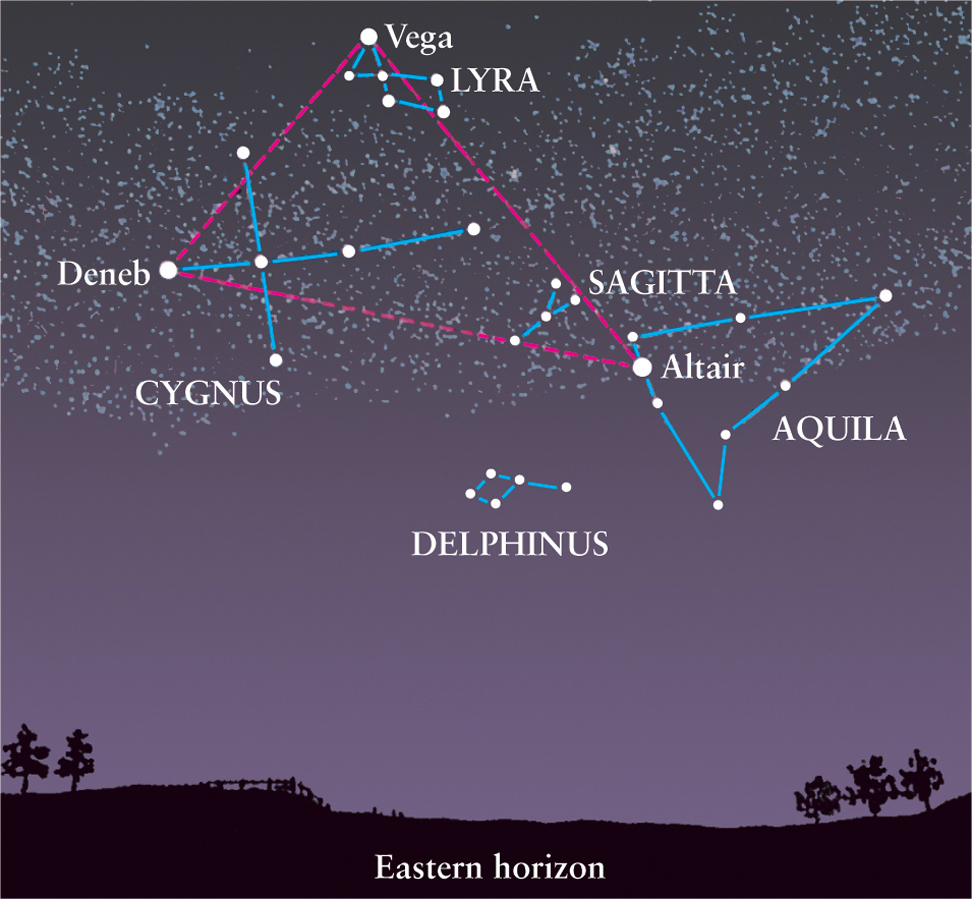

A similar feature, the “summer triangle,” graces the summer sky in the northern hemisphere. This triangle connects the brightest stars in Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), and Aquila (the Eagle) (Figure 1-6). A conspicuous portion of the Milky Way forms a beautiful background for these constellations, which are nearly overhead during the middle of summer at midnight.

Note that all the star charts in this section and at the end of this book are drawn for an observer in the northern hemisphere. If you live in the southern hemisphere, you can see constellations that are not visible from the northern hemisphere, and vice versa. In the next section we will see why this is so.

Question

ConceptCheck 1-2: If Jupiter is reported to be in the constellation of Taurus the Bull, does Jupiter need to be within the outline of the bull’s body? Why or why not?

Answer appears at the end of the chapter.