Use process narratives to explain.

Explanatory process narratives often relate particular experiences or elucidate processes followed by machines or organizations. Let us begin with an excerpt from a remembered-event essay by Mary Mebane. She uses process narrative to let readers know what happened the first time she worked on an assembly line putting tobacco leaves on the conveyor belt:

The job seemed easy enough as I picked up bundle after bundle of tobacco and put it on the belt, careful to turn the knot end toward me so that it would be placed right to go under the cutting machine. Gradually, as we worked up our tobacco, I had to bend more, for as we emptied the hogshead we had to stoop over to pick up the tobacco, then straighten up and put it on the belt just right. Then I discovered the hard part of the job: the belt kept moving at the same speed all the time and if the leaves were not placed on the belt at the same tempo there would be a big gap where your bundle should have been. So that meant that when you got down lower, you had to bend down, get the tobacco, straighten up fast, make sure it was placed knot end toward you, place it on the belt, and bend down again. Soon you were bending down, up; down, up; down, up. All along the line, heads were bobbing—down, up; down, up—until you finished the barrel. Then you could rest until the men brought you another one.

—MARY MEBANE, “Summer Job”

Temporal transitions and simple past-tense verbs place the actions in time.

Here, narrative actions (bend down, get the tobacco, straighten up fast) become a series of staccato movements (down, up; down, up; down, up) that emphasize the speed and machinelike actions Mebane had to take to keep up with the conveyor belt.

The next example shows how a laser printer functions:

To create a page, the computer sends signals to the printer, which shines a laser at a mirror system that scans across a charged drum. Whenever the beam strikes the drum, it removes the charge. The drum then rotates through a toner chamber filled with thermoplastic particles. The toner particles stick to the negatively charged areas of the drum in the pattern of characters, lines, or other elements the computer has transmitted and the laser beam mapped.

Once the drum is coated with toner in the appropriate locations, a piece of paper is pulled across a so-called transfer corona wire, which imparts a positive electrical charge. The paper then passes across the toner-coated drum. The positive charge on the paper attracts the toner in the same position it occupied on the drum. The final phase of the process involves fusing the toner to the paper with a set of high-temperature rollers.

—RICHARD GOLUB AND ERIC BRUS, Almanac of Science and Technology

Because the objects performing the action change from sentence to sentence, the writers must construct a clearly marked chain, introducing the object’s name in one sentence and repeating the name or using a synonym in the next.

Like Mebane’s process narrative, this one sequences the actions chronologically from beginning (“the computer sends signals to the printer”) to end (“fusing the toner to the paper”). Temporal transitions (then, once, then, final), present-tense verbs, and narrative actions (sends, shines, scans, strikes) convey the passage of time and place the actions clearly in this chronological sequence.

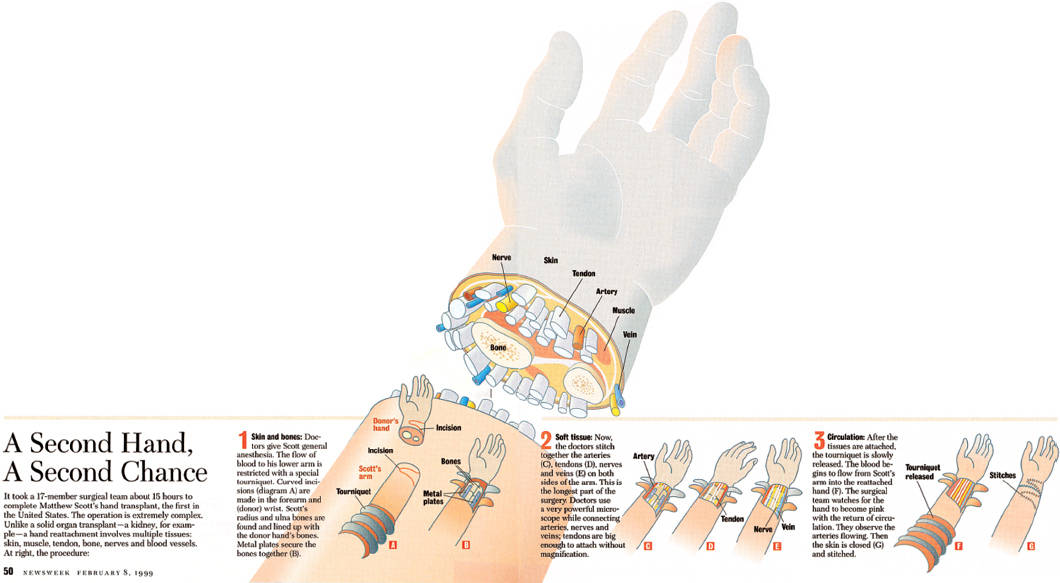

Our last explanatory process narrative is a graphic sidebar of the type commonly used in magazines and books. This one comes from a Newsweek magazine feature on Matthew Scott, the third person ever to receive a hand transplant. “A Second Hand, A Second Chance,” shown in Figure 14.2, illustrates the process narrative.

Notice that this process narrative integrates writing with graphics. The procedure is divided into three distinct steps, with each step clearly numbered and labeled (1. Skin and bones). In each step, the figure captions refer to the graphics with letters—Curved incisions (diagram A). The graphics themselves incorporate labels—Donor’s hand, Incision, Tourniquet released. The writer uses some basic narrating strategies to present the actions and make clear the sequence in which they were taken: temporal transitions (now, while, after), present-tense verbs, and narrative actions, mostly in the form of active verbs (secure, stitch, watches). Much is left out, of course. Readers could not duplicate the procedure based on this narrative, but it does give Newsweek readers a clear sense of what was done during the fifteen hours of surgery.

EXERCISE 14.8

In Chapter 3, read paragraph 6 (p. 64) of Brian Cable’s profile of a local mortuary, “The Last Stop.” Here Cable narrates the process that the company follows once it has been notified of a client’s death. As you read, look for and mark the narrating strategies discussed in this chapter that Cable uses. Then reflect on how well you think the narrative presents the actions and their sequence.