A Sample Analysis

In a composition class, students were asked to do a short written analysis of a photograph. In looking for ideas, Paul Taylor came across the Library of Congress’s Documenting America, an exhibit of photographs taken 1935–45. Gordon Parks’s photographs struck Paul as particularly interesting, especially those of Ella Watson, a poorly paid office cleaner employed by the federal government. (See Figure 20.3.)

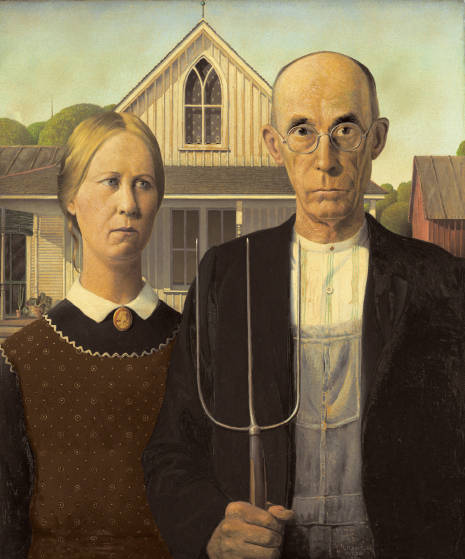

FIGURE 20.3 Ella Watson, Gordon Parks (1942)

|

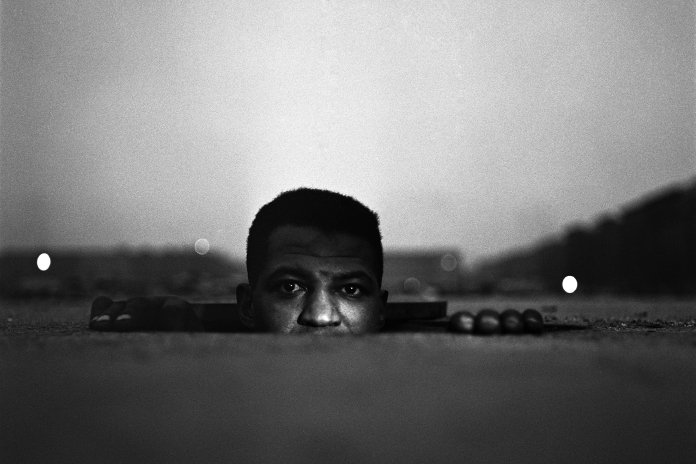

FIGURE 20.4 American Gothic, Grant Wood (1930) Source: The Art Institute of Chicago. © Figge Art Museum, successors to the estate of Nan Wood Graham/VAGA.

|

After studying the photos, Paul read about Parks’s first session with Watson:

My first photograph of [Watson] was unsubtle. I overdid it and posed her, Grant Wood style, before the American flag, a broom in one hand, a mop in the other, staring straight into the camera.1

Paul didn’t understand Parks’s reference to Grant Wood in his description of the photo, so he did an Internet search and discovered that Parks was referring to a classic painting by Wood called American Gothic (Figure 20.4). Reading further about the connection, he discovered that Parks’s photo of Watson is itself commonly titled American Gothic and discussed as a parody of Grant Wood’s painting.

After learning about the connection with American Gothic, Paul read more about the context of Parks’s photos:

Gordon Parks was born in Kansas in 1912. . . . During the Depression a variety of jobs . . . took him to various parts of the northern United States. He took up photography during his travels. . . . In 1942, an opportunity to work for the Farm Security Administration brought the photographer to the nation’s capital; Parks later recalled that “discrimination and bigotry were worse there than any place I had yet seen.”2

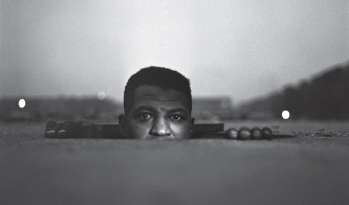

Intrigued by what he had learned so far, Paul decided to delve into Parks’s later career. A 2006 obituary of Parks in the New York Times reproduced his 1952 photo Emerging Man, which Paul decided to analyze for his assignment. First he did additional research on the photo. Then he made notes on his responses to the photo using the criteria for analysis provided on pp. 628–29.

PAUL TAYLOR’S ANALYSIS OF EMERGING MAN

KEY COMPONENTS OF THE VISUAL

Composition

- Of what elements is the visual composed? It’s a black-and-white photo showing the top three-quarters of a man’s face and his hands (mostly fingers). He appears to be emerging out of the ground -- out of a sewer? There’s what looks like asphalt in the foreground, and buildings (out of focus) in the far background.

- What is the focal point—that is, the place your eyes are drawn to? The focal point is the face of the man staring directly into the camera’s lens. There’s a shaft of light angled (slightly from the right?) onto the lower-middle part of his face. His eyes appear to glisten slightly. The rest of his face, his hands, and the foreground are in shadow.

- From what perspective do you view the focal point? We appear to be looking at him at eye level -- weird, since eye level for him is just a few inches from the ground. Was the photographer lying down? The shot is also a close-up -- a foot or two from the man’s face. Why so close?

- What colors are used? Are there obvious special effects employed? Is there a frame, or are there any additional graphical elements? There’s no visible frame or any graphic elements. The image is in stark black and white, and there’s a “graininess” to it: we can see the texture of the man’s skin and the asphalt on the street.

People/Other Main Figures

- If people are depicted, how would you describe their age, gender, subculture, ethnicity, profession, level of attractiveness, and socioeconomic class? The man is African American and probably middle-aged (or at least not obviously very young or very old). We can’t see his clothing or any other marker of class, profession, etc. The fact that he seems to be emerging from a sewer implies that he’s not hugely rich or prominent, of course -- a “man of the people”?

- Who is looking at whom? Do the people represented seem conscious of the viewer’s gaze? The man seems to be looking directly into the camera and at the viewer (who’s in the position of the photographer). I guess, yes, he seems to look straight at the viewer -- perhaps in a challenging or questioning way.

- What do the facial expressions and body language tell you about power relationships (equal, subordinate, in charge) and attitudes (self-confident, vulnerable, anxious, subservient, angry, aggressive, sad)? We can only see his face from the nose up, and his fingertips. It looks like one eyebrow is slightly raised, which might mean he’s questioning or skeptical. The expression in his eyes is definitely serious. The position of his fingers implies that he’s clutching the rim of the manhole -- that, and the title, indicate that he’s pulling himself up out of the hole. But since we see only the fingers, not the whole hand, does his hold seem tenuous -- he’s “holding on by his fingertips”? Not sure.

Scene

- If a recognizable scene is depicted, what is its setting? What is in the background and the foreground? It looks like an urban setting (asphalt, manhole cover, buildings, and lights in the blurry distant background). Descriptions of the photo note that Parks shot the image in Harlem. Hazy buildings and objects are in the distance. Only the man’s face and fingertips are in focus. The sky behind him is light gray, though -- is it dawn?

- What has happened just before the image was “shot”? What will happen in the next scene? He appears to be coming up and out of the hole in the ground (the sewer).

- What, if anything, is happening just outside of the visual frame? It’s not clear. There’s no activity in the background at all. It’s deserted, except for him.

Words

- If text is combined with the visual, what role does the text play? There’s no text on or near the image. There is the title, though -- Emerging Man.

- Does the text help you interpret the visual’s overall meaning? The title is a literal description, but it might also refer to the civil rights movement -- the gradual racial and economic integration -- of African Americans into American society.

- What is the tone of the text? Hard to say. I guess, assuming wordplay is involved, it’s sort of witty (merging traffic?).

Tone

- What tone, or mood, does the visual convey? What elements in the visual (color, composition, words, people, setting) convey this tone? The tone is serious, even perhaps a bit spooky. The use of black and white and heavy shadows lends a somewhat ominous feel, though the ray of light on the man’s face, the lightness of the sky, and the lights in the background counterbalance this to an extent. The man’s expression is somber, though not obviously angry or grief-stricken.

CONTEXT(S)

Rhetorical Context

- What is the visual’s main purpose? Given Parks’s interest in politics and social justice, it seems fair to assume that the image of the man emerging from underground -- from the darkness into the light? -- is a reference to social progress (civil rights movement) and suggests rebirth of a sort. The use of black and white, while certainly not unusual in photographs of the era, emphasizes the division between black and white that is in part the photo’s subject.

- Who is its target audience? Because it appeared first in Life, the target audience was mainstream -- a broad cross-section of the magazine-reading U.S. population at mid-twentieth century.

- Who is the author? Who sponsored its publication? During this era, Gordon Parks was best known as a photographer whose works documented and commented on social conditions. The fact that this photo was originally published in Life (a mainstream periodical read by white Americans throughout the country) is probably significant.

- If the visual is embedded within a document that is primarily written text, how do the written text and the visual relate to each other? The photo accompanied an article about Ellison’s Invisible Man, a novel about a man who goes underground to escape racism and conflicts within the early civil rights movement. Now the man is reentering mainstream society?

- Social Context. What is the immediate social and cultural context within which the visual is operating? The civil rights movement was gaining ground in post–World War II society.

- Historical Context. What historical knowledge does it assume the audience already possesses? For a viewer in 1952, the image would call to mind the current and past situation of African Americans. Uncertainty about what the future would hold (Would the emergence be successful? What kind of man would eventually emerge?) would be a big part of the viewer’s response. Viewers today obviously feel less suspense about what would happen in the immediate (post-1952) future. The “vintage” feel of the photo’s style and even the man’s hair, along with the use of black and white, probably have a “distancing” effect on the viewer today. At the same time, the subject continues to be relevant--most viewers will likely think about the progress we’ve made in race relations and where we’re currently headed.

- Intertextuality. How does the visual connect, relate to, or contrast with any other significant texts, visual or otherwise, that you are aware of? Invisible Man, which I’ve already discussed, was a best-seller and won the National Book Award in 1953.

After writing and reviewing these notes and doing some further research to fill in gaps in his knowledge about Parks, Ellison, and the civil rights movement, Paul drafted his analysis. He submitted this draft to his peer group for comments, and then revised. His final draft follows.

Taylor 1

Paul Taylor

Professor Stevens

Writing Seminar I

4 October 2012

The Rising

Gordon Parks’s 1952 photograph Emerging Man (Fig. 1) is as historically significant a reflection of the civil rights movement as are the speeches of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, the music of Mahalia Jackson, and the books of Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin. Through striking use of black and white--a reflection of the racial divisions plaguing American cities and towns throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries--and a symbolically potent central subject--an African American man we see literally “emerging” from a city manhole--Parks’s photo evokes the centuries of racial and economic marginalization of African Americans, at the same time as it projects a spirit of determination and optimism regarding the civil rights movement’s eventual success.

In choosing the starkest of urban settings and giving the image a gritty feel, Parks alerts the viewer to the gravity of his subject and gives it a sense of immediacy. As with the documentary photographs Parks took of office cleaner Ella Watson for the Farm Security Administration in the 1940s--see Fig. 2 for one example--the carefully chosen setting and the spareness of the treatment ensure the viewer’s focus on the social statement the artist is making (Documenting). Whereas the photos of Ella Watson document a particular woman and the actual conditions of her life and work, however, Emerging Man strips away any particulars, including any name for the man, with the result that the photo enters the symbolic or even mythic realm.

The composition of Emerging Man makes it impossible for us to focus on anything other than the unnamed subject rising from the manhole--we are, for instance, unable to consider what the weather might be, though we might surmise from the relatively light tone of the sky and the emptiness of the street that it is dawn. Similarly, we are not given any specifics of the setting, which is simply urban and, apart from the central figure, unpopulated. Reducing the elements to their outlines in this way keeps the viewer focused on the grand central theme of the piece: the role of race in mid-twentieth-century America and the future of race relations.

The fact that the man is looking directly at the camera, in a way that’s challenging but not hostile, speaks to the racial optimism of the period among many African Americans and whites alike. President Truman’s creation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights in 1946 and his 1948 Executive Order for the integration of all armed services were significant steps toward the emergence of the full-blown civil rights movement, providing hope that African Americans would be able, for perhaps the first time in American history, to look directly into the eyes of their white counterparts and fearlessly emphasize their shared humanity (Leuchtenburg). The “emerging man” seems to be daring us to try to stop his rise from the manhole, his hands gripping its sides, his eyes focused intently on the viewer.

According to several sources, Parks planned and executed the photograph as a photographic counterpart to Ralph Ellison’s 1952 Invisible Man, a breakthrough novel about race and society that was both a best-seller and a critical success. Invisible Man is narrated in the first person by an unnamed African American man who traces his experiences from boyhood. The climax of the novel shows the narrator hunted by policemen controlling a Harlem race riot; escaping down a manhole, the narrator is trapped at first but eventually decides to live permanently underground, hidden from society (“Ralph Ellison”). The correspondences between the photo and the book are apparent. In fact, according to the catalog accompanying an exhibit of Parks’s photos selected by the photographer himself before his death in 2006, Ellison actually collaborated on the staging of the photo (Bare Witness).

More than just a photographic counterpart, however, it seems that Parks’s Emerging Man can be read as a sequel to Invisible Man, with the emphasis radically shifted from resignation to optimism. The man who had decided to live underground now decides to emerge, and does so with determination. In this compelling photograph, Parks--himself an “emerging man,” considering he was the first African American photographer to be hired full-time by the widely respected mainstream Life magazine-- created a photograph that celebrated the changing racial landscape in American society.

Works Cited

Bare Witness: Photographs by Gordon Parks. Catalog. Milan: Skira; Stanford, CA: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2006. Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Resource Library. Web. 29 Sept. 2012.

Documenting America: Photographers on Assignment. 15 Dec. 1998. America from the Great Depression to World War II: Black-and-White Photographs from the FSA-OWI, 1935-1945. Prints and Photographs Div., Lib. of Cong. Web. 27 Sept. 2012.

Leuchtenburg, William E. “The Conversion of Harry Truman.” American Heritage 42.7 (1991): 55-68. America: History & Life. Web. 29 Sept. 2012.

Parks, Gordon. Ella Watson. Aug. 1942. America from the Great Depression to World War II: Black-and-White Photographs from the FSA-OWI, 1935-1945. Prints and Photographs Div., Lib. of Cong. Web. 27 Sept. 2012.

- - - . Emerging Man. 1952. PhotoMuse. George Eastman House and ICP, n.d. Web. 26 Sept. 2012.

“Ralph Ellison: Invisible Man.” Literature and Its Times: Profiles of 300 Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them. Ed. Joyce Moss and George Wilson. Vol. 4. Gale Research, 1997. Literature Resource Center. Web. 30 Sept. 2012.

EXERCISE 20.1

Dorothea Lange’s First-Graders at the Weill Public School shows children of Japanese descent reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in San Francisco, California, in 1942. Following the steps below, write an essay suggesting what the image means.

- Do some research on Lange’s work. (Like Paul Taylor, you might start at the Library of Congress’s online exhibit Documenting America, which features Lange, along with Gordon Parks and other photographers.)

- Analyze the image using the criteria for analysis presented on pp. 628–29.

- From this preliminary analysis, develop a tentative thesis that says what the image means and how it communicates that meaning.

- With this thesis in mind, plan your essay, using your analysis of the image to illustrate your thesis. Be aware that as you draft your essay, your thesis will develop and may even change substantially.

Question

EXERCISE 20.2

Analyze one of the ads that follow by using the criteria for visual analysis on pp. 628–29. Be sure to consider the role that writing plays in the ad’s overall meaning. Write an essay with a thesis that discusses the ad’s central meaning and significance.

Magazine Ad for Continental Savings Bank (2008)

|

Magazine Ad for Jell-O (2012)

|

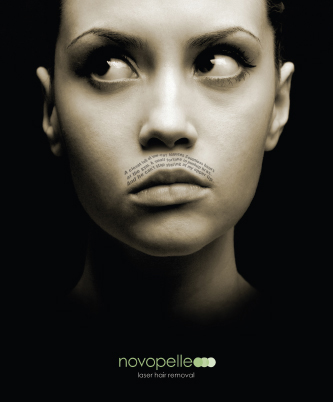

Magazine Ad for Novopelle Laser Hair Removal (2008) (Text reads: “A closet full of low-cut blouses. Countless hours at the gym. A small fortune in pushup bras. And he can’t stop staring at my upper lip.”)

|

Question

EXERCISE 20.3

Find an ad or public service announcement that you find compelling in its use of visuals. Analyze the ad by using the criteria for visual analysis on pp. 628–29. Be sure to consider the role that writing plays in the ad’s overall meaning. Write an essay with a thesis that discusses the ad’s central meaning and significance.