Conduct surveys.

Surveys let you gauge the opinions and knowledge of large numbers of people. You might conduct a survey to gauge opinion in a political science course or to assess familiarity with a television show for a media studies course. You might also conduct a survey to assess the seriousness of a problem for a service-learning class or in response to an assignment to propose a solution to a problem (Chapter 7). This section briefly outlines procedures you can follow to carry out an informal survey, and it highlights areas where caution is needed. Colleges and universities have restrictions about the use and distribution of questionnaires, so check your institution’s policy or obtain permission before beginning the survey.

Designing Your Survey

Use the following tips to design an effective survey:

- Conduct background research. You may need to conduct background research on your topic. For example, to create a survey on scheduling appointments at the student health center, you may first need to contact the health center to determine its scheduling practices, and you may want to interview health center personnel.

- Focus your study. Before starting out, decide what you expect to learn (your hypothesis). Make sure your focus is limited—focus on one or two important issues—so you can craft a brief questionnaire that respondents can complete quickly and easily and so that you can organize and report on your results more easily.

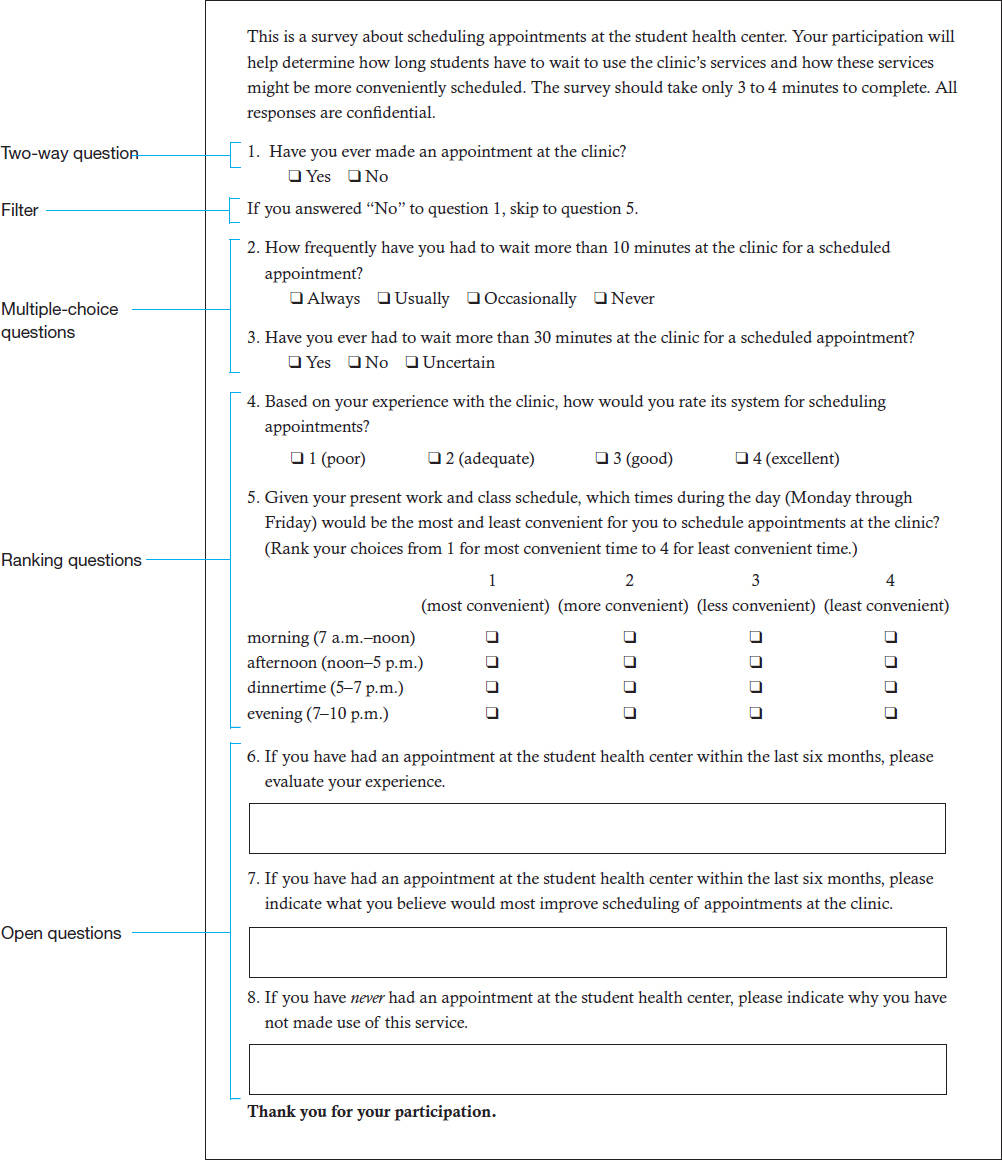

- Write questions. Plan to use a number of closed questions(questions that request specific information), such as two-way questions, multiple-choice questions, ranking scale questions, and checklist questions (see Figure 24.4). You will also likely want to include a few open questions(questions that give respondents the opportunity to write their answers in their own words). Closed questions are easier to tally, but open questions are likely to provide you with deeper insight and a fuller sense of respondents’ opinions. Whatever questions you develop, be sure that you provide all the answer options your respondents are likely to want, and make sure your questions are clear and unambiguous.

- Identify the population you are trying to reach. Even for an informal study, you should try to get a reasonably representative group. For example, to study satisfaction with appointment scheduling at the student health center, you would need to include a representative sample of all the students at the school—not only those who have visited the health center. Determine the demographic makeup of your school, and arrange to reach out to a representative sample.

- Design the questionnaire. Begin your questionnaire with a brief, clear introduction stating the purpose of your survey and explaining how you intend to use the results. Give advice on answering the questions, estimate the amount of time needed to complete the questionnaire, and—unless you are administering the survey in person—indicate the date by which completed surveys must be returned. Organize your questions from least to most complicated or in any order that seems logical, and format your questionnaire so that it is easy to read and complete.

- Test the questionnaire. Ask at least three readers to complete your questionnaire before you distribute it. Time them as they respond, or ask them to keep track of how long they take to complete it. Discuss with them any confusion or problems they experience. Review their responses with them to be certain that each question is eliciting the information you want it to elicit. From what you learn, revise your questions and adjust the format of the questionnaire.

Administering the Survey

The more respondents you have, the better, but constraints of time and expense will almost certainly limit the number. As few as twenty-five could be adequate for an informal study, but to get twenty-five responses, you may need to solicit fifty or more participants.

You can conduct the survey in person or over the telephone; use an online service such as SurveyMonkey (surveymonkey.com) or Zoomerang (zoomerang.com); e-mail the questionnaires; or conduct the survey using a social media site such as Facebook. You may also distribute surveys to groups of people in class or around campus and wait to collect their responses.

Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, face-to-face surveys allow you to get more in-depth responses, but participants may be unwilling to answer personal questions face to face. Though fewer than half the surveys you solicit using survey software are likely to be completed (your invitations may wind up in a spam folder), online software will tabulate responses automatically.

Writing the Report

When writing your report, include a summary of the results, as well as an interpretation of what the results mean.

- Summarize the results. Once you have the completed questionnaires, tally the results from the closed questions. (If you conducted the survey online, this will have already been done for you.) You can give the results from the closed questions as percentages, either within the text of your report or in one or more tables or graphs. Next, read all respondents’ answers to each open question to determine the variety of responses they gave. Summarize the responses by classifying the answers. You might classify them as positive, negative, or neutral or by grouping them into more specific categories. Finally, identify quotations that express a range of responses succinctly and engagingly to use in your report.

- Interpret the results. Once you have tallied the responses and read answers to open questions, think about what the results mean. Does the information you gathered support your hypothesis? If so, how? If the results do not support your hypothesis, where did you go wrong? Was there a problem with the way you worded your questions or with the sample of the population you contacted? Or was your hypothesis in need of adjustment?

-

Write the report. Reports in the social sciences use a standard format, with headings introducing the following categories of information:

- Abstract: A brief summary of the report, usually including one sentence summarizing each section

- Introduction: Includes context for the study (other similar studies, if any, and their results), the question or questions the researcher wanted to answer and why this question (or these questions) are important, and the limits of what the researcher expected the survey to reveal

- Methods: Includes the questionnaire, identifies the number and type of participants, and describes the methods used for administering the questionnaire and recording data

- Results: Includes the data from the survey, with limited commentary or interpretation

- Discussion: Includes the researcher’s interpretation of results, an explanation of how the data support the hypothesis (or not), and the conclusions the researcher has drawn from the research