Veronica Chambers: The Secret Latina

| Veronica Chambers | The Secret Latina |

Formerly an editor for the New York Times Magazine and a culture writer for Newsweek, Veronica Chambers now serves as deputy editor, brand development, for Hearst Corporation, a major media company. She has written for a variety of other publications, including Vogue, Glamour, Esquire, and Essence, in which the following essay originally appeared. Additionally, she has written several books, among them the memoir Mama’s Girl (1997), the novel Miss Black America (2004), and a variety of nonfiction works, including Having It All? Black Women and Success (2004), The Joy of Doing Things Badly: A Girl’s Guide to Love, Life and Foolish Bravery (2006), and Kickboxing Geishas: How Modern Japanese Women Are Changing Their Nation (2010).

In this examination of growing up as a dark-skinned Latina in America, Chambers draws on her own experiences and on several vivid memories of her mother. As you read, consider what Chambers means by “the secret Latina” and how she explores all the facets of this identity.

1She’s a platanos-frying, malta Dukesa-drinking, salsa-dancing Mamacita—my dark-skinned Panamanian mother. She came to this country when she was 21, her sense of culture intact, her Spanish flawless. Even today, more than 20 years since she left her home country to become an American citizen, my mother still considers herself Panamanian and checks “Hispanic” on census forms.

2As a Black woman in America, my Latin identity is murkier than my mother’s, despite the fact that I, too, was born in Panama, and call that country “home.” My father’s parents came from Costa Rica and Jamaica, my mother’s from Martinique. I left Panama when I was 2 years old. My family lived in England for three years then came to the States when I was 5. Having dark skin and growing up in Brooklyn in the 1970’s meant I was Black, period. You could meet me and not know I was of Latin heritage. Without a Spanish last name or my mother’s fluent Spanish at my disposal, I often felt isolated from the Latin community. And frankly, Latinos were not quick to claim me. Latinos can be as racist as anybody else, favoring blue-eyed, blond rubias over negritas like me.

3I found it almost impossible to explain to my elementary-school friends why my mother would speak Spanish at home. They would ask if I was Puerto Rican and look bewildered when I told them I was not. To them, Panama was a kind of nowhere. There weren’t enough Panamanians in Brooklyn to be a force. Everybody knew where Jamaicans were from because of famous singers like Bob Marley. Panamanians had Ruben Blades, but most of my friends thought he was Puerto Rican, too.

4In my neighborhood, where the smell of somebody’s grandmother’s cooking could transform a New York corner into Santo Domingo, Kingston, or Port-au-Prince, a Panamanian was a sort of fish with feathers—assumed to be a Jamaican who spoke Spanish. The analogy was not without historical basis: A century ago, Panama’s black community was drawn to the country from all over the Caribbean largely as cheap labor to build the Panama Canal.

5My father didn’t mind that we considered ourselves black rather than Latino. He named my brother Malcolm X, and if my mother hadn’t put her foot down, I would have been called Angela Davis Chambers. It’s not that my mother didn’t admire Angela Davis, but you have only to hear how “Veronica Victoria” flows off her Spanish lips to know that she was homesick for Panama and for those names that sang like timbales on carnival day. So between my father and my mother was a black-Latin divide. Because of my father, we read and discussed books about black history and civil rights. Because of my mother, we ate Panamanian food, listened to salsa, and heard Spanish at home.

6Still, it wasn’t until my parents divorced when I was ten that my mother tried to teach Malcolm and me Spanish. She was a terrible language teacher. She had no sense of how to explain structure, and her answer to every question was “That’s just the way it is.” A few short weeks after our Spanish lessons began, my mother gave up, and we were all relieved. But I remained intent on learning my mother’s language. When she spoke Spanish, her words were a fast current—a stream of language that was colorful, passionate, fiery. I wanted to speak Spanish because I wanted to swim in the river of her words, her history, my history, too.

7At school, I dove into the language, matching what little I knew from home with all that I learned. One day, when I was in the ninth grade, I finally felt confident enough to start speaking Spanish with my mother. I soon realized that by speaking Spanish with her, I was forging an important bond. When I’d spoken only English, I was the daughter, the little girl. But when I began speaking Spanish, I became something more—a hermanita, a sisterfriend, a Panamanian homegirl who could hang with the rest of them. Eventually, this bond would lead me home.

8Two years ago, at age twenty-seven, I decided it was finally time. I couldn’t wait any longer to see Panama, the place my mother and my aunts had told me stories about. I enlisted my cousin Digna as a traveling companion, and we made arrangements to stay with my godparents, whom I had never met. We planned our trip for the last week in February—carnival time.

9Panama, in Central America, is a narrow sliver of a country: You can swim in the Caribbean Sea in the morning and backstroke across the Pacific in the afternoon. As our plane touched down, bringing me home for the first time since I was two, I felt curiously comfortable and secure. In the days that followed, there was none of the culture shock that I’d expected. I had my mother and aunts to thank for that. My godmother, Olga, reminded me of them. The first thing she did was book appointments for Digna and me to get our eyebrows plucked and our nails and feet done with Panamanian-style manicures and pedicures. “It’s carnival,” Aunt Olga said, “and you girls have to look your best.” We just laughed.

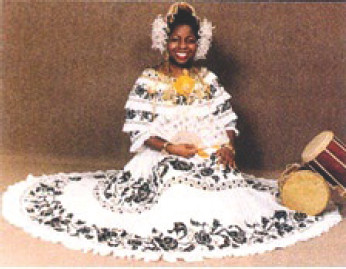

10In Panama, I went from being a lone black girl with a curious Latin heritage to being part of the Latinegro tribe or the Afro-Antillianos, as we were officially called. I was thrilled to learn there was actually a society for people like me. Everyone was black, everyone spoke Spanish, and everyone danced the way they danced at fiesta time back in Brooklyn, stopping only to chow down on a smorgasbord of souse, rice with black-eyed peas, beef patties, empanadas, and codfish fritters. The carnival itself was an all-night bacchanal with elaborate floats, brilliantly colored costumes, and live musicians. In the midst of all this, my godmother took my cousin and me to a photo studio to have our pictures taken in polleras, the traditional dress. After spending an hour on makeup and hair and donning a rented costume, I looked like Scarlett in Gone with the Wind.

11Back in New York, I gave the photo to my mother. She almost cried. She says she was so moved to see me in a pollera because it was “such a patriotic thing to do.” Her appreciation made me ridiculously happy; ever since I was a little girl, I’d wanted to be like my mother. In one of my most vivid memories, I am seven or eight years old, and my parents are having a party. Salsa music is blaring, and my mother is dancing and laughing. She sees me standing off in a corner, so she pulls me into the circle of grown-ups and tries to teach me how to dance to the music. Her hips are electric. She puts her hands on my sides and says, “Move these,” and I start shaking my hip bones as if my life depends on it.

12Now I am a grown woman, with hips to spare. I can salsa. My Spanish isn’t shabby. You may look at me and not know that I am Panamanian, that I am an immigrant, that I am both black and Latin. But I am my mother’s daughter, a secret Latina, and that’s enough for me.

Courtesy of Veronica Chambers

Source: Chambers, Veronica. “The Secret Latina.” Essence. July 2000: 102.