Melissa Mae, Laying Claim to a Higher Morality

| Melissa Mae | Laying Claim to a Higher Morality |

CONCERNED ABOUT both terrorism and our treatment of terror suspects, Melissa Mae asked her instructor if she could analyze the controversy about the U.S. government’s treatment of detainees suspected of terrorism. She read two published essays on torture recommended by her instructor, one coauthored by law professor Mirko Bagaric and law lecturer Julie Clarke, the other by retired Army chaplain Kermit D. Johnson. Mae decided to focus her essay more on their commonalities than on the obvious differences between them. As you read this essay, consider these questions:

- How well does Mae succeed in finding areas of potential common ground between the authors she is analyzing?

- How effectively does Mae maintain a neutral tone in presenting these different points of view on such a highly emotional issue? Point to any places where her position is evident, and indicate how you identified it.

1In 2004, when the abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib became known, many Americans became concerned that the government was using torture as part of its interrogation of war-on-terror detainees. Although the government denied a torture program existed, we now know that the Bush Administration did order what they called “enhanced interrogation techniques” such as waterboarding and sleep deprivation. The debate over whether these techniques constitute torture continues today.

2In 2005 and 2006, when Kermit D. Johnson wrote “Inhuman Behavior” and Mirko Bagaric and Julie Clarke wrote “A Case for Torture,” this debate was just heating up. Bagaric and Clarke, professor and lecturer, respectively, in the law faculty at Australia’s Deakin University, argued that torture is necessary in extreme circumstances to save innocent lives. Major Johnson, a retired Army chaplain, wrote that torture should never be used for any reason whatsoever. Although their positions appear to be diametrically opposed, some common ground exists, because the authors of both essays share a goal—the preservation of human life—as well as a belief in the importance of morality.

3The authors of both essays present their positions on torture as the surest way to save lives. Bagaric and Clarke write specifically about the lives of innocent victims threatened by hostage-takers or terrorists and claim that the use of torture in such cases to forestall the loss of innocent life is “universally accepted” as “self-defense.” Whereas Bagaric and Clarke think saving lives justifies torture, however, Johnson believes renouncing torture saves lives. Johnson asserts: “A clear-cut repudiation of torture or abuse is . . . essential to the safety of the troops” (26), who need to be able to “claim the full protection of the Geneva Conventions . . . when they are captured, in this or any war” (27).

4This underlying shared value—human life is precious—represents one important aspect of common ground between the two positions. In addition to this, however, the authors of both essays agree that torture is ultimately a moral issue, and that morality is worth arguing about. For Bagaric and Clarke, torture is morally defensible under certain, extreme circumstances when it “is the only means, due to the immediacy of the situation, to save the life of an innocent person”; in effect, Bagaric and Clarke argue that the end justifies the means. Johnson argues against this common claim, writing that “whenever we torture or mistreat prisoners, we are capitulating morally to the enemy—in fact, adopting the terrorist ethic that the end justifies the means” (26). Bagaric and Clarke, in their turn, anticipate Johnson’s argument and refute it by arguing that those who believe (as Johnson does) that “torture is always wrong” are “misguided.” Bagaric and Clarke label Johnson’s kind of thinking “absolutist,” and claim it is a “distorted” moral judgment.

5It is not surprising that, as a chaplain, Johnson would adopt a religious perspective on morality. Likewise, it should not be surprising that, as faculty at a law school, Bagaric and Clarke would take a more pragmatic and legalistic perspective. It is hard to imagine how they could bridge their differences when their moral perspectives are so different, but perhaps the answer lies in the real-world application of their principles.

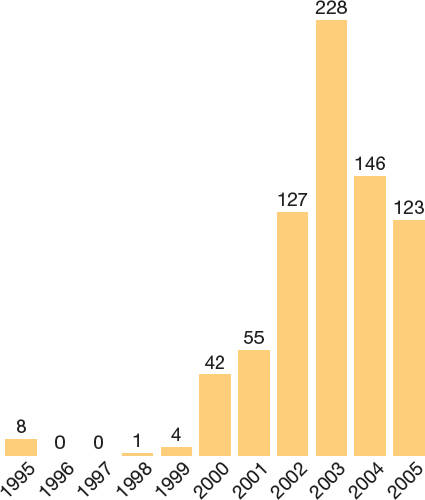

6The authors of these essays refer to the kind of situation typically raised when a justification for torture is debated: Bagaric and Clarke call it “the hostage scenario,” and Johnson refers to it as the “scenario about a ticking time bomb” (26). As the Parents Television Council has demonstrated (see fig. 1), scenes of torture dominated television in the period the authors were writing about, and may have had a profound influence on the persuasive power of the scenario.

7Johnson rejects the scenario outright as an unrealistic “Hollywood drama” (26). Bagaric and Clarke’s take on it is somewhat more complicated. First, Bagaric and Clarke ask the rhetorical question: “Will a real-life situation actually occur where the only option is between torturing a wrongdoer or saving an innocent person?” They initially answer, “Perhaps not.” Then, however, they offer the real-life example of Douglas Wood, a 63-year-old engineer taken hostage in Iraq and held for six weeks until he was rescued by U.S. and Iraqi soldiers.

8At first glance, they seem to offer this example to refute Johnson’s claim that such scenarios don’t occur in real life. However, a news report about the rescue of Wood published in the Age, where Bagaric and Clarke’s essay was also published, says that the soldiers “effectively ‘stumbled across Wood’ during a ‘routine’ raid on a suspected insurgent weapons cache” (“Firefight”). The report’s wording suggests that the Wood example does not really fit the Hollywood-style hostage scenario; Wood’s rescuers appear to have acted on information they got from ordinary informants rather than through torture.

9By using this example, rather than one that fits the ticking time bomb scenario, Bagaric and Clarke seem to be conceding that such scenarios are exceedingly rare. Indeed, they appear to prepare the way for a potentially productive common-ground-building discussion when they conclude: “Even if a real-life situation where torture is justifiable does not eventuate, the above argument in favour of torture in limited circumstances needs to be made because it will encourage the community to think more carefully about moral judgments.”

10Although Bagaric and Clarke continue to take a situational view of torture (considering the morality of an act in light of its particular situation) and Johnson does not waver in seeing torture in terms of moral absolutes, a discussion about real-world applications of their principles could allow them to find common ground. Because they all value the preservation of life, they already have a basis for mutual respect and might be motivated to work together to find ways of acting for the greatest good—to “lay claim to a higher morality” (26).

Works Cited

Bagaric, Mirko, and Julie Clarke. “A Case for Torture.” theage.com.au. The Age, 17 May 2005. Web. 1 May 2009.

“Firefight as Wood Rescued.” theage.com.au. The Age, 16 June 2005. Web. 2 May 2009.

Johnson, Kermit D. “Inhuman Behavior: A Chaplain’s View of Torture.” Christian Century 18 Apr. 2006: 26–27. Academic Search Premier. Web. 2 May 2009.