Erica Goode, The Gorge-Yourself Environment

| Erica Goode | The Gorge-Yourself Environment |

ERICA GOODE is an award-winning journalist who served as assistant managing editor at U.S. News & World Report before joining the New York Times, where she covers science and the environment. After earning a master’s degree in social psychology, Goode received fellowships from the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. She has won awards for her writing from the National Mental Health Association and the American Psychiatric Association.

Notice that even though writing for a newspaper and, therefore, not using an academic style of citing sources, Goode informs readers about her sources. As you read, consider the following:

- How effectively does Goode establish the credibility of her sources?

- What more, if anything, might she do to demonstrate their reliability? How would she present her sources differently if she were writing for an academic audience?

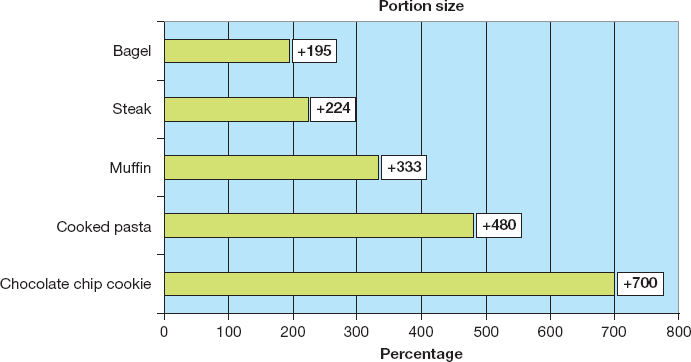

1From giant sodas to supersize burgers to all-you-can-eat buffets, America’s approach to food can be summed up by one word: Big. Plates are piled high, and few crumbs are left behind. Today’s blueberry muffin could, in an earlier era, have fed a family of four. But social norms change. . . . Traditionally, the prescription for shedding extra pounds has been a sensible diet and increased exercise. Losing weight has been viewed as a matter of personal responsibility, a private battle between dieters and their bathroom scales. But a growing number of studies suggests that while willpower obviously plays a role, people do not gorge themselves solely because they lack self-control. Rather, social scientists are finding, a host of environmental factors—among them, portion size, price, . . . the availability of food and the number of food choices presented—can influence the amount the average person consumes. “Researchers have underestimated the powerful importance of the local environment on eating,” said Dr. Paul Rozin, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, who studies food preferences. Give moviegoers an extra-large tub of popcorn instead of a container one size smaller and they will eat 45 to 50 percent more, as Dr. Brian Wansink, a professor of nutritional science and marketing at the University of Illinois, showed in one experiment. Even if the popcorn is stale, they will still eat 40 to 45 percent more. Keep a tabletop in the office stocked with cookies and candy, and people will nibble their way through the workday, even if they are not hungry. Reduce prices or offer four-course meals instead of single tasty entrees, and diners will increase their consumption.

2In a culture where serving sizes are mammoth, attractive foods are ubiquitous, bargains are abundant and variety is not just the spice but the staple of life, many researchers say, it is no surprise that waistlines are expanding. Dr. Kelly D. Brownell, a professor of psychology at Yale and an expert on eating disorders, has gone so far as to label American society a “toxic environment” when it comes to food. Health experts and consumer advocates point to the studies of portion size and other environmental influences in arguing that fast-food chains and food manufacturers must bear some of the blame for the country’s weight problem. “The food industry has used portion sizes and value marketing as very effective tools to try to increase their sales and profits,” said Margo Wootan, the director of nutrition policy at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, an advocacy group financed by private foundations. . . .

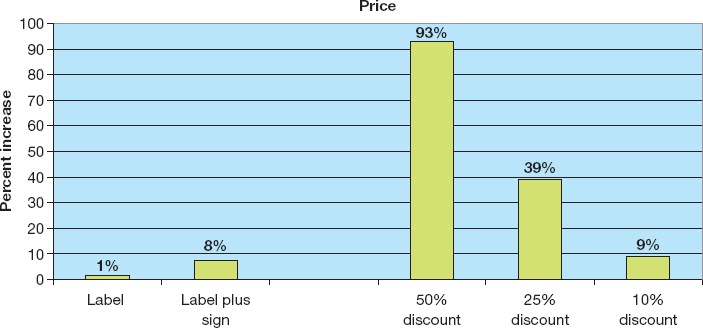

3. . . An increasing number of studies show that how food is served, presented and sold plays at least some role in what and how much people eat. Price is a powerful influence. In a series of studies, researchers at the University of Minnesota have demonstrated that the relative cost of different products has an even more potent effect on food choice than nutritional labeling. Dr. Simone French, an associate professor of epidemiology, and her colleagues manipulated the prices of high-fat and low-fat snacks in vending machines at 12 high schools and 12 workplaces. In some cases, the snacks were labeled to indicate their fat content. “The most interesting finding was that the price changes were whopping in effect,” compared with the labels, Dr. French said. Dropping the price of the low-fat snacks by even a nickel spurred more sales. In contrast, orange stickers signaling low-fat content or cartoons promoting the low-fat alternatives had little influence over which snacks were more popular.

4Packaging can change the amount people consume. Dr. Wansink and his colleagues have showed that, fooled by a visual illusion, people drink more from short, wide glasses than thinner, taller ones, but they think they are drinking less. Having more choices also appears to make people eat more. In one study, Dr. Barbara Rolls, whose laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has studied the effects of the environment on eating, found that research subjects ate more when offered sandwiches with four different fillings than they did when they were given sandwiches with their single favorite filling. In another study, participants served a four-course meal with meat, fruit, bread and a pudding—foods with very different tastes, flavors and textures—ate 60 percent more food than those served an equivalent meal of only their favorite course.

5To anyone who has survived Christmas season at the office, it will come as no surprise that the availability of food has an effect as well. Dr. Wansink and his colleagues varied the placement of chocolate candy in work settings over three weeks. When the candy was in plain sight on workers’ desks, they ate an average of nine pieces each. Storing the sweets in a desk drawer reduced consumption to six pieces. And chocolates lurking out of sight, a couple of yards from the desk, cut the number to three pieces per person.

6Researchers have long suspected that large portions encourage people to eat more, but studies have begun to confirm this suspicion only in the last several years. There is little question that the serving size of many foods has increased since McDonald’s introduced its groundbreaking Big Mac in 1968. For her doctoral dissertation, Dr. Lisa Young, now an adjunct assistant professor in the department of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, tracked portion sizes in national restaurant chains, in foods like cakes, bread products, steaks and sodas and in cookbook recipes from the 1970’s to the late 1990’s. The amount of food allotted for one person increased in virtually every category Dr. Young examined. French fries, hamburgers and soda expanded to portions that were two to five times as great as they had been at the beginning of the period Dr. Young studied. Steaks, chocolate bars and bread products grew markedly. Cookbooks specified fewer servings (and correspondingly larger portions) for the same recipe appearing in earlier editions. “Restaurants are using larger dinner plates, bakers are selling larger muffin tins, pizzerias are using larger pans and fast-food companies are using larger drink and French fry containers,” Dr. Young wrote in a paper published last year in The American Journal of Public Health. Even the cup holders in automobiles have grown larger to make room for giant drinks, Dr. Young noted.

7She and other experts think it is no coincidence that obesity began rising sharply in the United States at the same time that portion sizes started increasing. But cause and effect cannot be proved. And the food industry rejects the idea of a connection. Mr. Anderson of the restaurant association, for example, says that lack of exercise, poor eating habits and genetic influences are largely responsible for Americans’ struggle with extra fat. Still, in cultures where people are thinner, portion sizes appear to be smaller. Take France, where the citizenry is leaner in body mass and where only 7.4 percent of the population is obese, a contrast to America, where 22.3 percent qualify. Examining similar restaurant meals and supermarket foods in Paris and Philadelphia, Dr. Rozin and colleagues at Penn found that the Parisian portions were significantly less hefty. Cookbook portions were also smaller. Even some items sold at McDonald’s—the chicken sandwich, for example—are smaller than their American counterparts.

8“There is a disconnect between people’s understanding of portions and the idea that a larger portion has more calories,” said Dr. Marion Nestle, chairwoman of the N.Y.U. nutrition and food policy department and the author of “Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health.” The Double Gulp, a 64-ounce soft drink sold by 7-Eleven, Dr. Nestle noted, has close to 800 calories, more than a third of many people’s daily requirement, but she said people were often shocked to learn this. And, as studies by Dr. Rolls, Dr. Wansink and others suggest, faced with larger portions, people are likely to consume more, an effect, Dr. Rolls noted, that is not limited to people who are overweight. “Men or women, obese or lean, dieters, nondieters, plate-cleaners, non-plate-cleaners—it’s pretty much across the board,” she said. In one demonstration of this, Dr. Rolls and her colleagues varied the portions of ziti served at an Italian restaurant, keeping the price for the dish the same but on some days increasing the serving by 50 percent. On the days of the increase, Dr. Rolls said, customers ate 45 percent more, and while diners rated the bigger portion size as a better value, they deemed both servings appropriate. The researchers have also shown that after downing large plates of food, people do not usually compensate by eating less at their next meal. . . .

9Researchers have yet to cement the link between larger portions and a fatter public. But add up the studies, Dr. Rolls and other experts say, and it is clear Americans might have more success slimming down if plates were not quite so large and a tempting snack did not await on every corner. Obviously, people have responsibility for deciding what to eat and how much, Dr. Rolls said. “The problem is,” she said, “they’re not very good at it.”