Using Emotional Appeals

Printed Page 569

Humans have the capacity to experience a wide range of emotions—including empathy, anger, shame, fear, and pity—and each of these feelings provides an opportunity to enhance your use of pathos in a persuasive speech. For example, in a presentation in which a speaker advocated greater freedom in doctor selection for health maintenance organization (HMO) patients, she used the following emotional appeal:

Trey McPherson was born with half of his heart shrunken and nearly useless, a condition that causes most children to die in infancy.

Fortunately, Trey was not one of these victims because he was treated by a leading pediatric heart surgeon. After two surgeries, Trey’s parents were able to experience the joy of seeing their ten-month-old son climb out of his crib at the hospital. Except for a bandage on his tiny chest, it was difficult to tell that Trey had recently experienced open-heart surgery. Sadly, many babies are not as lucky as Trey. Although this skillful surgeon’s patients have far-above-average survival rates, many pediatric cardiologists in the New York area find that their “favorite surgeon is frequently off limits because of price if a child belongs to an HMO.”16

This example evokes a variety of emotions. It stimulates listeners’ anger and pity at the thought of small children being denied the best available care. It prompts them to empathize by imagining how they would feel if a loved one with a serious disease were forced to accept low-quality medical care. It also causes joy at the thought of how Trey’s parents must have felt when their child recovered from surgery.

But notice that this emotional appeal is accompanied by sound reasoning. The speaker provides evidence that Trey’s access to excellent care is atypical, which justifies the anger she evokes.

Click the "Next" button to try Video Activity 18.3, “Claims: Fact (Appeals to Emotion and Credibility).”

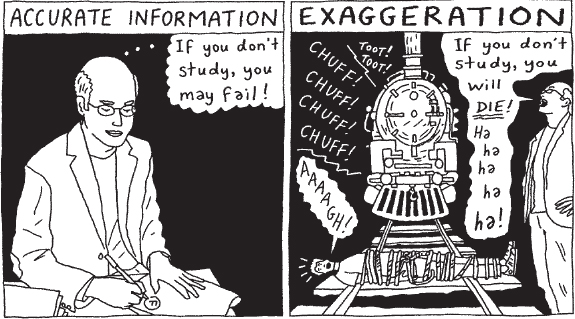

A fear appeal—an argument that arouses fear in the minds of audience members—can be a particularly powerful form of pathos.17 However, to be effective, a fear appeal must demonstrate a serious threat to listeners’ well-being.18 To be ethical, it must be based on accurate information and not exaggerated specifically to make your argument sound more persuasive.

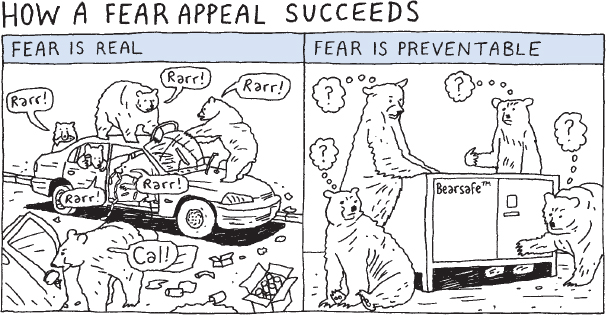

A fear appeal is also more likely to succeed if your audience members believe they have the power to remedy the problem you’re describing.19 Consider messages by National Park Service rangers advocating safe storage of food in national parks. The rangers provide statistics showing how often bears have broken into cars or tents when people have left food out. They augment these statistics with videos depicting bears smashing car windows and climbing inside the vehicles to get food. These images usually strike fear into viewers’ hearts. The rangers then show how easy it is to store food safely in lockers or bear-proof canisters. Because audience members realize they can readily adopt these practices, they do adopt them.

Effective word choice (see chapter 12) can also strengthen the power of an emotional appeal. When a speaker’s language connects with the values and passions of audience members, the persuasive impact of a message is enhanced. Political consultants on both the right and the left carefully consider the exact words that are used to express an idea to voters. Emory University psychology and psychiatry professor Drew Westen notes that “every word we utter activates what neuroscientists call networks of association—interconnected sets of thoughts and emotions.”20 The selection of metaphors, for instance, has a significant influence in framing how audience members perceive an issue. For example, labeling participants in armed conflict as “freedom fighters” primes the listener to have a more favorable view of the cause for which they are fighting.21 Westen’s counterpart, Dr. Frank Luntz, has had a highly successful career assessing the instant response of focus-group members who are exposed to different words used to communicate the same basic message and recommending optimal word choice for his clients.

How does this work? Take the example of the 2013 debate on solutions for the federal budget deficit. In an article in the Washington Post, Luntz noted that President Obama called for a “balanced, responsible approach” in nearly every speech because his consultants determined that such language would ring true to the American public. He suggested that the Republicans’ metaphor “kick the can down the road” did not convey an urgent need for action, and that claims that their opponents were committing “fiscal child abuse” were considered insulting. He recommended changing the language to “piling debt on our children” or “mortgaging the American dream.”22

Although it is unlikely you will be able to afford a high-priced consultant to help you choose the words that will be most compelling to your classmates, you can use your audience analysis to inform the language you select. If you express the key points of your message with words that relate to the values, needs, and aspirations of your audience members, your ideas are more likely to resonate. For example, in a classroom speech that took a stance on a campus issue, Taja advocated moving the campus’s print newspaper to an online-only format. Her audience analysis revealed that many students already read plenty of news and blogs online; however, these same students were concerned that losing the printed newspaper would break a long tradition and result in less reliable reporting. Thus, Taja argued that “the online format we all rely on today could not be a better match for the campus newspaper’s long tradition of excellent reporting,” depicting the change as a move from one medium to an even better one rather than a complete overhaul of the paper’s tradition of excellence. As was true for Taja, the words you choose to express your message can strengthen your persuasive appeal. However, they must also be used in an accurate and ethical manner.