Avoiding Loss of Your Credibility

Printed Page 549

You have many strategies at hand for enhancing your credibility during a speech. But there are just as many ways to make a misstep and erode your ethos while giving a talk. Anytime you say something that shows a lack of competence, trustworthiness, or goodwill, you damage your credibility.

Such errors are common during political campaigns, and you can probably think of examples of gaffes that dimmed the chances of a candidate for office. But we have also seen such errors hurt the credibility of student speakers. In your speeches, careful preparation can help you avoid credibility-draining mistakes. Here are some common sources of this type of error:

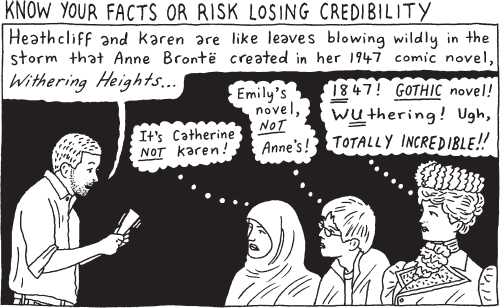

- Getting your facts wrong. Your competence and preparation will be questioned if you present factual information that is just plain inaccurate. Mushers and dog-show enthusiasts would immediately recognize the error of calling the Alaskan husky a purebred dog, as these sled dogs are crossbred from diverse bloodlines. Likewise, a speaker who mixed up the Brontë sisters would alienate fans of Victorian literature, and social networkers would tune out a presenter who mixed up a tweet and a Facebook status update. One of the benefits of selecting a topic you know well is that you are less likely to present factual errors on a familiar subject.

- Pronouncing words incorrectly. Your experience in a topic area will be questioned if you mispronounce the names of key persons or concepts related to the topic. For example, a student who referred to hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa (Bam-BAH-Tah) as Afrika BOM-bait-a would not be credible to audience members who know that genre of music well, and fans of renowned Italian tenor Andrea Bocelli (Ahn-DRAY-ah Bo-CHEL-ee) would question the credibility of a speaker who referred to him as AN-dree-a Bo-SELL-ee.

- Failing to acknowledge potential conflicts of interest. In chapter 17, we noted the importance of disclosing your biases. If you fail to acknowledge any vested interest in your topic, it will hurt your credibility when it is revealed. For example, suppose a classmate advocated a thousand-dollar scholarship for all students who serve in student government and asked the class to sign a petition supporting this policy. After class, you read an article in the campus newspaper and discover that the speaker serves in the student senate—no wonder he wanted that scholarship policy! You would view that student more suspiciously the next time he presented a speech and might be less inclined to vote for him in the next election.

- Stretching to find a connection with the audience. Have you ever seen speakers attempt to speak a language they do not know well, try to adopt local or professional slang, or feign interest in the audience members’ favorite sports team? They often end up mangling words or using terms incorrectly and get distracted from their message while worrying about possible mistakes. These errors only highlight how disconnected a speaker is. Local dialect can also be a challenge—for example, when speakers addressing a Missouri audience must decide whether to refer to the state as Missouree or Missouruh.4 You should always show respect to your audience, but the best choice is to be your authentic self. If a change in your typical pronunciation seems forced rather than sincere, you will lose credibility.

Once a speaker’s credibility has come into question, it’s very difficult to repair the damage. Thus, before giving a speech, examine the language you intend to use, and make sure that it communicates competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill. However, even bulletproof ethos isn’t enough to deliver an effective speech. You also need to deliver a solid set of facts to prove the claims you’re making.