PUBLIC SPEAKING: A GREAT TRADITION

Printed Page 13

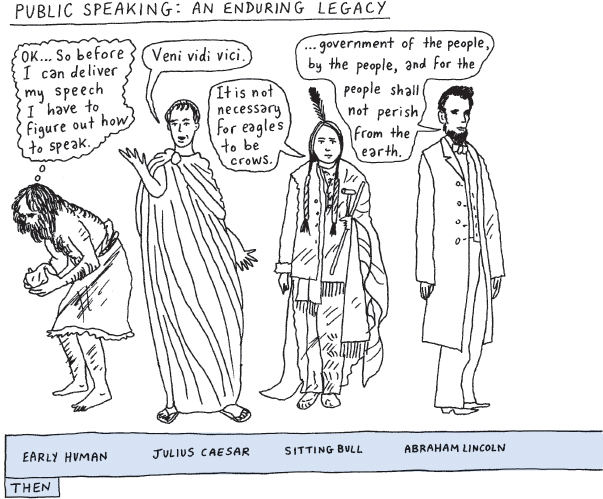

For centuries, people around the world have studied the art and practice of public speaking and used public address to inform, influence, and persuade others.

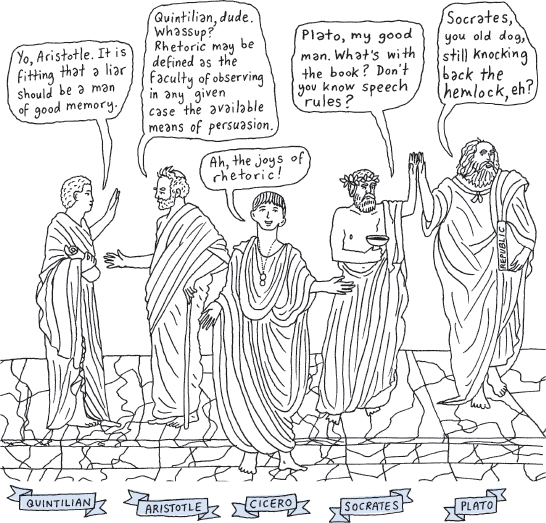

As far back as the fifth century B.C.E., all adult male citizens in the Greek city-state of Athens had a right to speak out in the assembly and vote on proposals relating to civic matters. Sometimes as many as six thousand citizens attended these meetings.11 Indeed, the ancient Greeks were the first people to think formally about rhetoric as well as teach it as a subject. A century later, the Greek scholar Aristotle wrote Rhetoric, a systematic analysis of the art and practice of public speaking. Many of Aristotle’s ideas influence the study of public speaking even today. Later, in first-century B.C.E. Rome, senators vehemently debated the issues of the day. Cicero, a Roman politician, was a renowned orator and a prolific writer on rhetoric, the craft of public speaking. Another noteworthy Roman rhetorician, Quintilian, emphasized the ideal of an ethical orator—the good person speaking well.

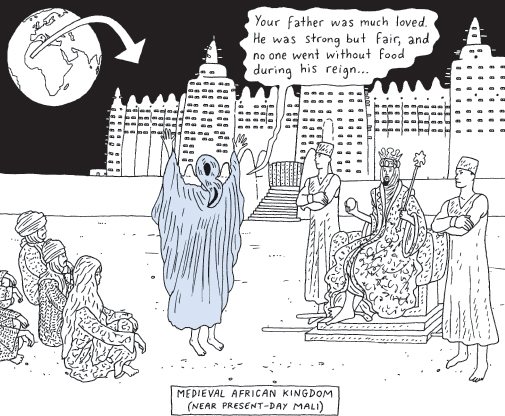

The tradition of public speaking, however, was not limited to Greece and Rome—it’s been practiced in many regions throughout history. From the time of Confucius in the fifth century B.C.E. until the end of the third century B.C.E., China enjoyed an intellectual climate whose energy rivaled that of ancient Greece.12 Scholars traveling throughout China passionately advocated a variety of systems of political and economic philosophy. In fifteenth-century western Africa, traveling storytellers recited parables and humorous stories, while in northeastern Africa, Islamic scholars embarked on lecture tours attended by large crowds.13 On feast days in one African kingdom (near present-day Mali), it was traditional for a bard to dress in a bird’s-head mask and deliver a speech encouraging the king to live up to his predecessors’ high standards.14 In seventeenth-century India, a speaker’s words were valued over other means of communication, and inscribed versions of the messages were referred to as “treasure houses of the Goddess of Speech.”15 Native Americans prized oratory, too; indeed, many deemed oratorical ability a more important leadership quality than even bravery in battle.16

The United States also has a rich history of public speaking. During the Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s, preachers sought to revive waning religious zeal in the colonies, often preaching in fields to accommodate the many listeners. During the American Revolution in the second half of the eighteenth century, colonists took to the streets to passionately decry new taxes and also launched the famous Boston Tea Party, in which they dressed as Mohawk Indians, boarded three ships in Boston Harbor, and hurled the vessels’ cargoes of tea overboard. In the 1770s and 1780s, political leaders in each of the states energetically debated the merits of ratifying the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

In the nineteenth century, public speaking became a hallmark of American society, as people debated political issues, expanded their knowledge, and even entertained one another. Political debates drew particularly large and enthusiastic crowds, such as the 1858 Senate seat debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. More than fifteen thousand people gathered to hear the contenders in Freeport, Illinois—a town with just five thousand residents.17

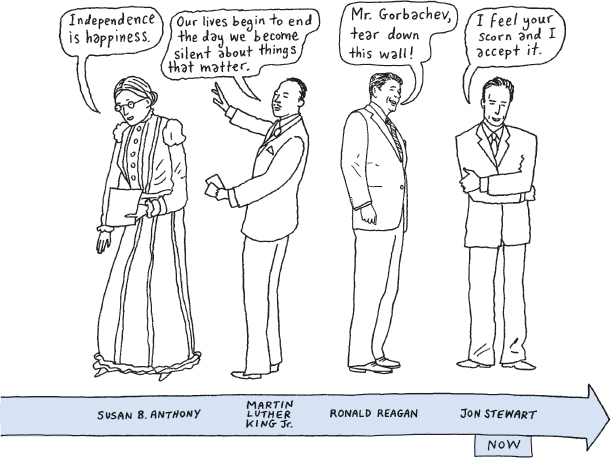

The antislavery movement of this time also used public speaking to drive major social change. Frederick Douglass, a former slave who moved audiences with his depictions of life under slavery, counted among the most compelling antislavery speakers. Women also actively participated in the American Anti-Slavery Society, holding offices and delivering public lectures. Angelina Grimké was just one eloquent orator who won audience members’ commitment to the antislavery cause with graphic descriptions of the slave abuse she had witnessed while growing up in South Carolina. Other women—such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone—took leadership roles in the women’s suffrage movement, which arose in the early 1900s. These able orators used fiery speeches to convince Americans that women deserved the right to cast a ballot at the polls—a radical notion at the time.18

During the twentieth century, public address continued to play a key role in American and world affairs, especially from political leaders throughout both world wars and the Great Depression. In August 1963, a whopping 250,000 people gathered near the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., to hear Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech,19 an address that instantly excited the imaginations of people around the world. In June of that same year, President John F. Kennedy traveled to Berlin to speak to an audience of over 400,000, voicing his support of those blocked in by the Berlin Wall—built by German leaders after World War II to prevent emigration. Kennedy famously showed his solidarity with Berliners by declaring “ich bin ein Berliner” (“I am a Berliner”).

Click the "Next" button to try Video Activity 1.2, “Kennedy, I Am a Berliner.”

Twenty-four years later, President Ronald Reagan traveled to the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and challenged Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev with the iconic words, “Tear down this wall!” The wall was finally opened in 1989. In the 1990s, the Million Man and the Million Woman marches culminated in public speeches by activists on such issues as job creation, human rights, and respect for African Americans.20

Today, new means of digital communication (e-mail, smartphones, videoconferences) mean that people can connect with large audiences like never before. However, leaders in many industries continue to rely on “in-person” public addresses to reach an audience—for example, politicians still spend much of their time speaking to live audiences on the campaign trail.