CODES OF ETHICS: ABSOLUTE, SITUATIONAL, AND CULTURALLY RELATIVE

Printed Page 69

How do people make ethical choices? Some adopt a code of behavior that they commit to using consistently. These individuals are demonstrating ethical absolutism—the belief that people should exhibit the same behavior in all situations. For instance, you would be using ethical absolutism if you decided to tell your romantic partner how you really felt about the sweater. In this case, your code of ethics might contain a principle saying, “People should always tell the truth, even if doing so hurts loved ones.”

Other people use situational ethics—which holds that correct behavior can vary depending on the situation at hand. Joe, for example, would be (inappropriately) using situational ethics if he decided that under the extenuating circumstances, it would be OK for him to plagiarize “just this once.”

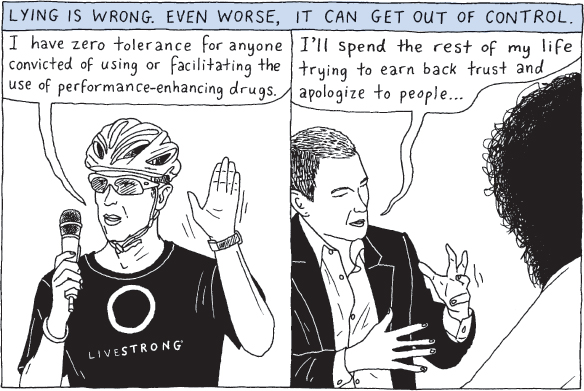

Whether you tend to see ethical decisions in absolute or situational terms, there are some generalizations that apply in most situations. For example, most societies believe that it’s more ethical to tell the truth than to lie. In the context of public speaking, most people believe that lying is wrong. They see it as an ethical violation, not to mention (in some circumstances) a possible violation of the law.

Yet some of these same individuals might think little or nothing of intentionally exaggerating their qualifications during a job interview—especially if they believe that “everybody does it and gets away with it.” Thus, many people use a blend of approaches to making ethics-related choices. In truth, most people are not strictly absolutists; even those who generally follow a strict ethical code may sometimes face dilemmas that compel them to engage in situational ethics, and all of us face such situations at some point in our lives.

In this book, we do not presume to tell you what your ethical system must be; we do insist, however, that you always strive to make the most ethical choice. To help you with such choices, in this chapter we expose you to the kinds of communication-related ethical dilemmas that speakers and audience members sometimes face, and we also explore behaviors most people consider unethical. As you’ll discover, one guiding principle that can help you make ethical choices is that of respect for other people—the old adage of treating others how you would want to be treated, as well as avoiding treating them in ways you would not want to be treated. For instance, if you would resent a public speaker who had withheld important information in order to persuade you to take a particular action, you shouldn’t exhibit that same behavior in your own speeches.

Ethics can also vary across societies, making them culturally relative.1 For example, in some cultures, people consider knowledge to be something that is owned collectively rather than by individuals. In cultures with strong oral and narrative traditions, for example, stories are passed from one generation to another and are shared as general cultural knowledge. In such cultures, people don’t consider working together or paraphrasing without attribution to be cheating or any other form of unethical behavior. When discussing ethics in this book, we reflect a Western cultural perspective, which holds that individuals do own the knowledge they create. This perspective informs the academic guidelines and honor codes that are explicitly stated by most colleges and universities in the United States—indeed, you will often find these guidelines cited in your instructors’ syllabi. Thus, we require proper citation and attribution of sources for all speeches.

As you read on, consider your own approach to making ethical decisions while developing and delivering presentations. What are your beliefs regarding proper behavior in general and in public speaking in particular? Do you always honor these beliefs strictly, or only in certain situations? To help you answer these questions, let’s consider some of the ethical issues you may confront. These include communicating truthfully, crediting others’ work, using sound reasoning, and behaving ethically when you’re listening to someone else’s speech. Though making ethical choices in public speaking situations can sometimes be difficult, this chapter helps you develop a responsible system for doing so. The key word here is responsibility. Whenever you give a speech, you wield power—over what your listeners think, how they feel, and what actions they end up taking—and are thus responsible for your audience’s well-being. The following sections offer guidelines for shouldering that responsibility by exhibiting ethically responsible behavior in public speaking.