False Inference

Printed Page 75

When a speaker presents information that leads listeners to an incorrect conclusion, that speaker has caused a false inference. Speakers who commit this ethical breach intentionally drop hints designed to make their audience believe something that isn’t true. For example, in a presentation titled “UFOs, Extraterrestrials, and the Supernatural,” a student described a series of events that occurred in a Midwestern town: an increase in the number of babies with birth defects, a rise in the rate of kidnapping, and a jump in the amount of farmland seized by the federal government. This student did not say outright that there was a government conspiracy to conceal the presence of aliens and UFOs, but he clearly intended his audience to draw this inference. In reality, the increase in birth defects amounted to exactly one—from six to seven. The rising kidnapping rate was actually a statewide statistic, caused by a change in laws about divorce and child custody. And the government seizure of land had happened—but only for the construction of a highway overpass. The speaker had unethically arranged his facts in such a way as to make his audience conclude that the government was trying to conceal the presence of aliens, X-Files–style.

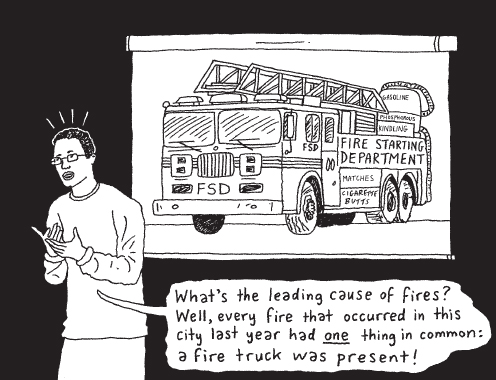

False inferences can also occur accidentally, like when a speaker gathers insufficient data and therefore unknowingly presents an incomplete understanding of the speech topic to the audience. Creating accidental false inferences isn’t unethical, but it prevents you from conveying accurate information to your audience, thus damaging the effectiveness of your speech. To avoid causing an accidental or a deliberate false inference, avoid overgeneralized claims based on statistical findings, and always explain to your audience what the statistics mean and how they were derived.

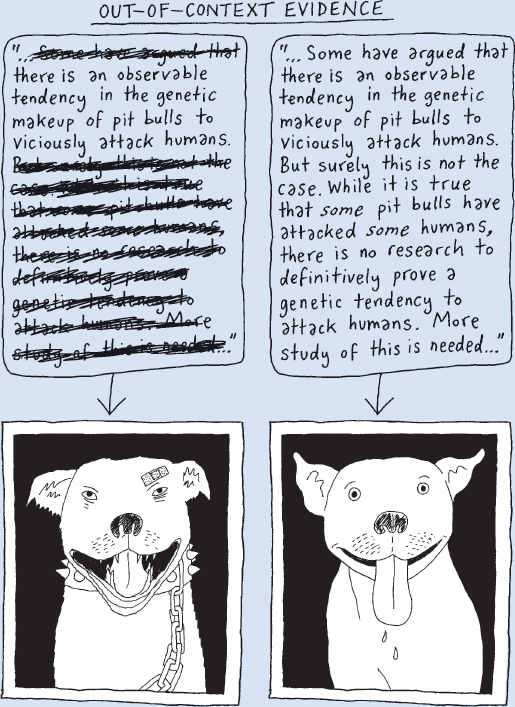

Taking evidence out of context is another form of false inference. Here, the speaker shares a source’s data or statements without explaining how they relate to the original situation. The speaker uses these facts or words selectively to support an argument. For example, in a speech about the propensity of pit bulls to attack people, one student quoted an animal-behavior expert out of context to imply a genetic predisposition toward attack: “[T]here is an observable tendency in the genetic makeup of pit bulls to viciously attack humans.” The student did not explain to her audience that the quotation came from a longer statement that clearly defies this view:

Some have argued that there is an observable tendency in the genetic makeup of pit bulls to viciously attack humans. But surely this is not the case. While it is true that some pit bulls have attacked some humans, there is no research to definitively prove a genetic tendency to attack humans. More study of this is needed.

Philosophers—and cheating romantic partners—have long argued about whether keeping silent about something is the same thing as lying about it. Thus, omission is another source of false inference. Here, presenters mislead the audience not by what they say but by what they leave unsaid. For example, in a presentation about on-campus drug use, a student government representative was asked about the extent of drug use and abuse in her campus dormitory. In response, she merely smiled and moved on to another question. Her silence and body language implied that there was no drug problem in her dormitory, but in fact, her dorm had the worst record for on-campus substance abuse. If silence about a topic will mislead your audience, and if you are aware of this likelihood but withhold information anyway, you have acted unethically through omission. Such actions suggest that you view your listeners as consumers of information and take an unethical and cynical caveat emptor (let the buyer beware) approach to public speaking.

To communicate truthfully and therefore ethically, never lie, never tell half-truths, and never cause false inferences—whether by taking evidence out of context or by omitting pertinent information. There are always alternatives. For example, if you fear that the truth may weaken your argument, then you need to do further research and perhaps take a closer look at your stance. Still, remember that there are at least two sides to every issue, as well as multiple solutions and perspectives to consider. If you fear what the audience might think if they knew the truth, consider the opposite: how will they react if they learn you have deceived them? In most situations, listeners will react to a lie much more negatively than to an unwelcome truth.