ACKNOWLEDGING THE WORK OF OTHERS

Printed Page 78

Researching a speech topic exposes you to a wealth of interesting facts, information, and ideas—many of which you will want to include in your presentation. But finding these materials also raises some questions: Should you include a particular piece of information in your presentation? If so, how should you use it? And how will you acknowledge its source?

Click the "Next" button to try Video Activity 3.1, “Citing Sources (Statistics and Testimony).”

Listeners—and especially speech instructors—want speakers to demonstrate their own ideas and thinking during a presentation. At the same time, all of us recognize that most speeches can be enhanced by research and examples from outside sources. The question is, how should you reconcile these objectives? To do so, you must use a blend of materials that demonstrates your own ideas and also ethically incorporates and acknowledges the original ideas of others. This approach is honest for you and fair to your listeners and sources.

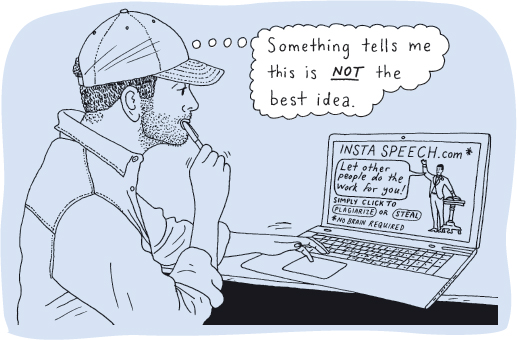

Imagine coming across an article or a published essay addressing the same topic as your speech—as Joe did when he was rushing to complete his speech preparation. Maybe you admire the way the author worded her prose; would it be a problem to incorporate a few lines from the article word-for-word without citing the quotations? What about taking a preponderance of the ideas from the publication and rewording them but not attributing them to the author? Would that be unethical? The answer to these questions is an unequivocal “Yes!”

Presenting another person’s words or ideas as if they were your own is called plagiarism, and it is always unethical. Plagiarism is “the deliberate and knowing presentation of another person’s original ideas or creative expressions as one’s own.”2 If you plagiarize, you mislead your audience by misrepresenting the source of the material you’ve used. Unfortunately, plagiarism is increasingly common at colleges and universities—and much of that owes to the rise of the Internet.3 Students may feel that plagiarism is a lesser evil than other kinds of cheating and use rationales to excuse it (“I don’t have time,” “No will one find out”).4 However, these are still just excuses for unethical behavior. When you plagiarize, you are stealing the ideas and words of another person—a crime most colleges and universities consider worthy of expulsion.

Though plagiarism is wrong, people sometimes have difficulty discerning the line between plagiarism and appropriate use of researched material. To illustrate why, let’s consider plagiarism in two contexts: quoting from a source and paraphrasing the work of others.