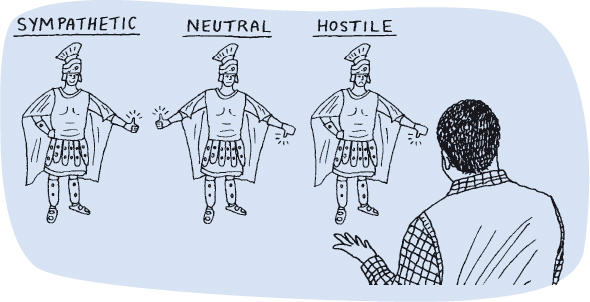

IDENTIFYING AUDIENCE DISPOSITION

Printed Page 147

Finally, complete your audience analysis by assessing listeners’ disposition—their likely attitude toward your message. In most situations, audiences can be divided into three groups: sympathetic, hostile, and neutral.

A sympathetic audience already agrees with your message or holds you in high personal esteem and will therefore respond favorably to your speech. For example, imagine that you are giving a speech advocating the controversial and hot-button issue of gun control to an audience made up of American Medical Association members—in this case, surgeons who work in emergency departments, often on victims of gun violence. More than likely, you will have found a sympathetic audience.

In contrast, a hostile audience opposes your message or you personally and will therefore resist listening to your speech. Imagine, for example, that you are giving the same speech advocating gun control, but this time you are a speaker at a convention of the National Rifle Association (NRA). The audience in this instance would likely be hostile to your message, since the NRA strongly opposes restrictions on gun ownership.

A third type of audience is the neutral audience, which has neither negative nor positive opinions about you or your message. Listeners may be neutral for several reasons. Some may be apathetic and simply not interested in you or your ideas. Others may be very interested in hearing you talk but lack strong feelings about your topic. The key thing to remember about neutral audiences is that depending on how you deliver your speech, they can tip toward supporting your message or opposing it. To extend the earlier example, imagine that you are now giving the same speech on gun control to the American Bar Association, an organization for lawyers. The membership of this association has mixed attitudes about gun control and would likely be considered a neutral audience.

As with the other elements of audience analysis, gauging your listeners’ disposition can help you figure out how to craft your speech. For example, suppose you’ll be facing a uniformly hostile audience. In this case, you should probably define realistic goals for your speech. Though you may not be able to persuade your listeners to follow a course of action you recommend, you might succeed in getting them to reevaluate their opposition to your message or to you personally. Thus, seek incremental or small changes, as opposed to a complete turnaround in attitudes.

An excellent example of this is when the late senator Edward (Ted) Kennedy was invited to speak in October 1983 at Liberty Baptist College, a conservative Christian school established by Reverend Jerry Falwell. Kennedy, a well-known liberal lawmaker, agreed to speak at the school, though he knew he would face a hostile audience. For his speech, Kennedy addressed the emotionally charged subject of separating church and state. His speech, titled “Truth and Tolerance in America,” focused on the appropriate place for religion in discourse about politics. In a speech that at times found common ground with Baptists and Reverend Falwell himself, Kennedy carefully but clearly encouraged religious groups to enter political discourse where moral and ethical questions were concerned. He also suggested they avoid name-calling or disparaging those who disagreed. It is unlikely Kennedy convinced many in the audience to change their minds about contentious issues like abortion—but he did gain the audience’s respect for working to find some commonality with them.8 Indeed, after Kennedy’s speech, a bond of sorts between Kennedy and Falwell was established, and it remained to the end of their lives.9

If you’re addressing a sympathetic audience, you don’t need to bother investing a lot of time and energy in trying to convince listeners that your ideas have merit or that you’re a credible speaker. Instead, push for more commitment: rather than simply asking your audience members to agree with you, urge them to act on your message.

If you’ll be facing a neutral audience, determine whether your listeners’ neutrality stems from apathy, disinterest, or a lack of firm conviction about you or the issue at hand. Then figure out how to overcome these forces of neutrality and get your listeners to support you—not oppose you.

Note, though, that many audiences don’t fit neatly into just one dispositional group. In most cases, some listeners in a particular audience will be hostile, others sympathetic, and still others neutral. You’ll need to tread carefully to deliver the most effective speech possible. If most of the people in your audience are neutral, a small percentage are sympathetic, and the remaining few are hostile and very vocal, what should you do? Expend just enough effort to silence the hostile listeners, make an equally modest effort to motivate your sympathetic listeners to act on your message, and devote the lion’s share of your energy to reaching your neutral listeners—and persuading them to take your side.