Introduction to Chapter 12

334

12

LANGUAGE AND STYLE

Look for the  and

and  throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

335

“Choose your words carefully.”

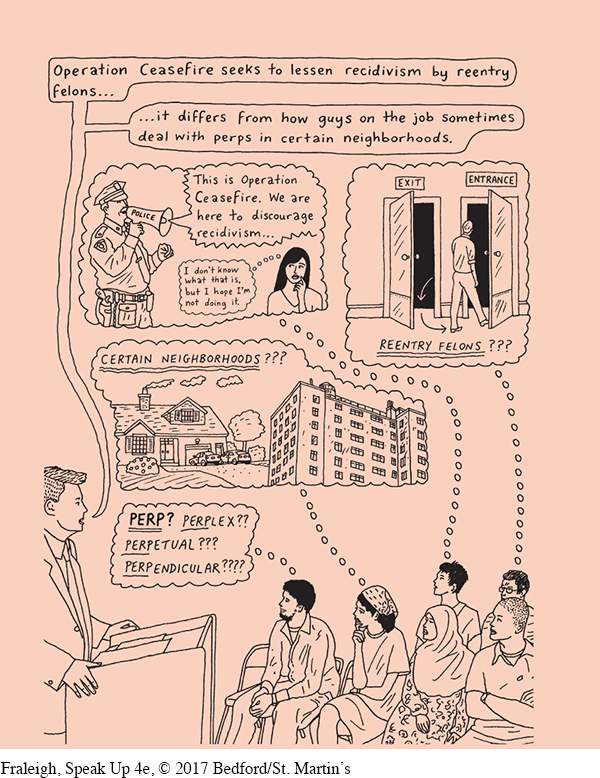

Marvin was eager to present his speech about a law-

Marvin’s classmates, however, had mixed reactions to his talk. Many found him credible because of his wide vocabulary of police slang and legal jargon, but others found his language impenetrable. Several audience members resented his use of phrases such as “guys on the job” for “police officers.” Some listeners felt that the phrase “certain neighborhoods” was a veiled reference to socioeconomics, and others felt that it suggested racial profiling and reminded them that some police officers were too quick to use violence against African American males—

336

Clearly, Marvin failed to convey his message to many in his audience—

Similarly, word choice factored heavily in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which we discuss in Chapter 2. When King presented this address on August 28, 1963, at the March on Washington, he didn’t give it an official title. Only later did people start calling it the “I Have a Dream” speech. Why has this phrase endured in people’s memories? It was an exceptionally powerful expression that encapsulated King’s vision of a time and place that would be free from prejudice and discrimination. Nearly fifty years after his death, people still experience profound emotions when they recall this expression. If King had calmly used the words “I hope” instead of “I have a dream,” he would have had much less effect on his listeners.

337

An average speech may contain hundreds or even thousands of words, and every one of them matters. Selected carefully, your words can help you connect with your audience and get your message across clearly. Used thoughtlessly, they may confuse, offend, bore, or annoy your listeners, preventing them from absorbing your message. In this chapter, we examine the importance of choosing the right words for your speeches and the differences between oral and written language. Then we explain how to use language to present your message clearly, express your ideas effectively, and demonstrate respect for your audience.