Introduction to Chapter 17

504

17

PERSUASIVE SPEAKING

Look for the  and

and  throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

505

“Good persuaders make strategic choices in an ethical manner.”

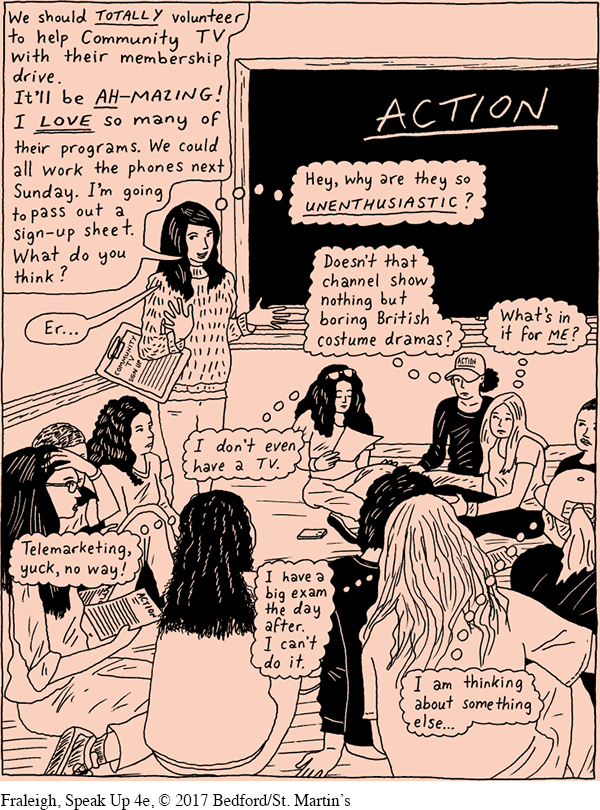

Kaliya was excited about a community service opportunity she discovered. The local public television station was going to hold a membership drive, and the station manager was looking for groups that could spend four hours on the phones helping callers set up their pledges. She couldn’t wait for the next meeting of ACTION, her service club on campus, so that she could ask the members to volunteer at the station, which broadcasted several of her favorite programs.

At the next club meeting, Kaliya stood up and presented her idea. She listed the programs that were scheduled that day on the station and talked about the mission of public television. Then she suggested that the club volunteer as a group to work on the phones at the membership drive on Sunday from 3 to 7 p.m. Finally, she passed out a sign-

Kaliya had made a common error that frustrates the best intentions of those attempting to persuade others to adopt their ideas. Although she loved her local public television station, she had not considered how other club members might respond to her plan. For one thing, she failed to explain how volunteering would benefit the participants—

506

Kaliya should have done more to tailor her message to the audience. She might have drawn club members into her speech by asking about popular public television shows that they probably watched as children. Because she knew many club members well, she might have focused on programs she knew they would like rather than listing every show on the schedule. She might have told listeners that this service opportunity would be helpful when they went job searching because many local businesses supported this station. If she had interested her listeners, then they would have been more attentive when she explained that they would be taking calls from people who wanted to donate—

As Kaliya discovered firsthand, knowing how to speak persuasively is a vital skill in all areas of life. Consider your own situation: Do you want to get a new policy adopted on campus? Advance in your career? Influence members of your community to support an important cause? Convince your roommate to listen to the music you want to hear? Win a major contract for your company from a new customer? Get an extension on the deadline of a paper? In these and many other cases, you’ll need to master the art of persuasive speaking if you hope to generate the outcomes you want.

In this chapter, we introduce the topic of persuasive speaking. We start by explaining the nature of a persuasive speech, followed by the process of persuasion. Then we show you how to select your thesis, main points, and supporting materials based on your audience analysis. We also consider the ethical obligations of a persuasive speaker and present several strategies for organizing your persuasive message. In the following chapter, we go into more detail about specific methods of persuasion.