Ensuring Ethical Use of Pathos

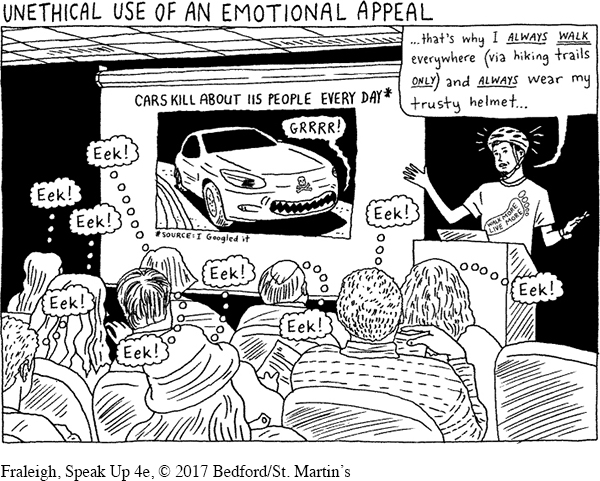

As we’ve discussed, emotional appeals, when combined with ethos and logos, can be very effective. But emotional appeals can have a dark side, too. You may be able to persuade some of your audience members even if you don’t establish a sound connection between your point and the emotion you are invoking, but your appeal will not be logical and certainly will not be ethical. This is unacceptable. History is replete with persuaders (including Adolf Hitler) who used pathos to achieve unethical and even horrific ends. Recall the old adage “With great power comes great responsibility,” and don’t use emotional appeals to manipulate your audience.

Let’s take the HMO example previously discussed. The key to that appeal to pathos was that the speaker used sound reasoning to connect a relatively rare health emergency (a baby born with a damaged heart) with a broader challenge facing many potential patients (access to a wide selection of qualified physicians). If the speaker had failed to make the logical connection between the points, however, she would have been acting unethically. How might that happen? Suppose she could not provide evidence that access to a wide range of doctors would actually help families in Trey’s situation and other health crises as well. In that case, her speech would merely be an emotional ploy to manipulate the audience into accepting her argument.

Numerous examples of fear appeals are premised on “facts” that are blatantly untrue. One instance involves politicians who offer “misbeliefs about the alleged risks of autism and other injuries from childhood vaccines” despite detailed analyses of vaccine safety that “disprove completely claims of vaccine-

Page 565

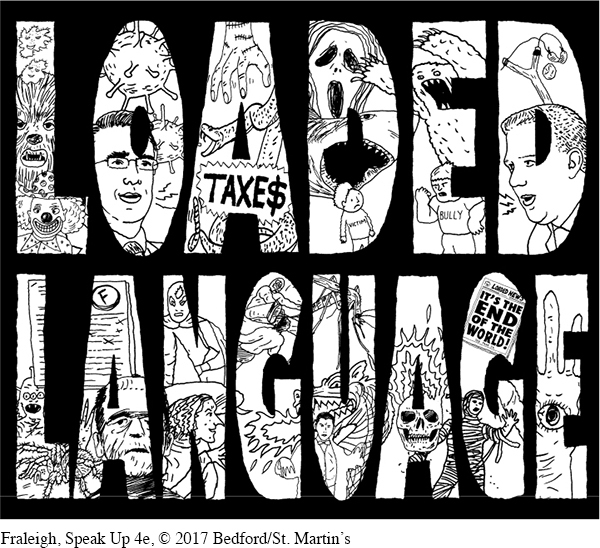

Ethical speakers also must ensure that they select language that accurately describes the ideas they are discussing. Although compelling word choice can be used as an ethical persuasive tool, it can cross the line into manipulation, exaggeration, or untruth. The loaded language fallacy is committed when emotionally charged words convey a meaning that cannot be supported by the facts presented by the speaker. For example, a speaker arguing against a proposal to tax sugar-

Page 566