Avoiding Logical Fallacies

Reasoning is fallacious (faulty) when the link between your claim and supporting material is weak. We briefly mention several fallacies in Chapter 3 in the context of unethical persuasion—

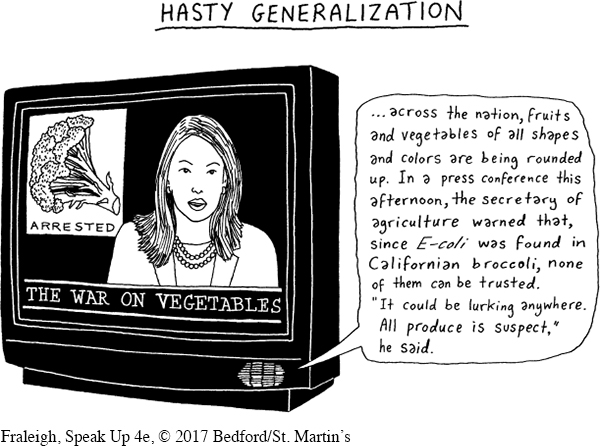

Hasty Generalization. When using example reasoning, be sure to avoid hasty generalization. This fallacy occurs when a speaker bases a conclusion on limited or unrepresentative examples. For example, it would be fallacious to reason that jobs could be created in any city whose leaders put their minds to it based on the example of Austin, Texas. Austin has a number of unique job-

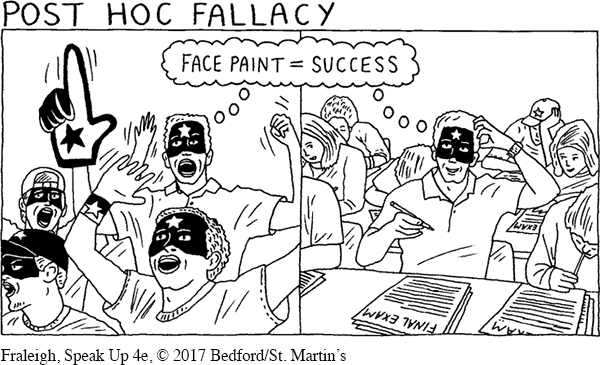

Causal Reasoning Errors. One common error in causal reasoning is the post hoc fallacy. The fallacy lies in the assumption that just because one event followed another, the first event caused the second. But this sequence of events, in itself, does not prove causality. For example, suppose a college expands the size of its library, and students’ grades subsequently increase. It might be tempting to conclude that the expansion of the library caused the improvement in grades. However, other factors could have led to the higher grades—

Page 554

Page 555

It’s also important to watch out for reversed causality, in which speakers miss the fact that the effect is actually the cause. For example, an improvement in students’ academic quality may have led the college to expand the library to accommodate the study habits of these highly motivated students.

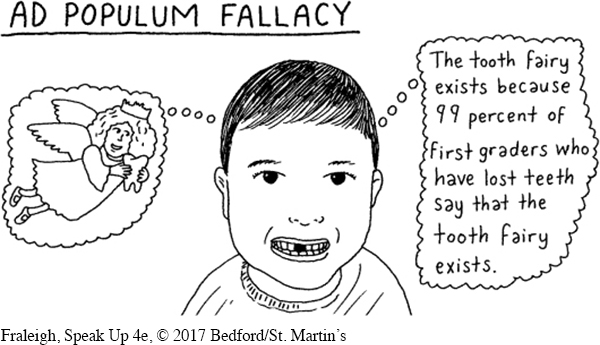

Ad Populum (Bandwagon) Fallacy. You’ve committed the ad populum (bandwagon) fallacy if you assume that a statement (for example, “The police are adequately trained to avoid excessive force,” “Millennials and members of Generation X will receive no social security benefits when they retire,” or “Sending U.S. troops to the Middle East to attack ISIS would reduce the risk of terrorism”) is true or false simply because a large number of people say it is. (Ad populum is Latin for “to the people.”)

The problem with basing the truth of a statement on the number of people who believe it is that most people have neither the expertise nor the time to conduct the research needed to arrive at an informed opinion about the big questions of the day. For this reason, it’s best to avoid using public-

Ad Hominem (Personal Attack) Fallacy. Some speakers try to compensate for weak arguments by making personal attacks against an opponent rather than addressing the issue in question. These speakers have committed the ad hominem (personal attack) fallacy. (Ad hominem is Latin for “to the person.”) For example, in a campaign speech for student body president, one candidate referred to her opponent as a “tree-

Page 556

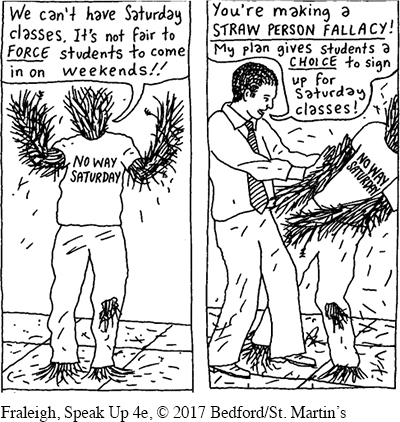

Straw Person Fallacy. You commit the straw person fallacy if you replace your opponent’s real claim with a weaker claim that you can more easily rebut. This weaker claim may sound relevant to the issue, but it is not; you’re presenting it just because it’s easy to knock down, like a person made of straw.

During the 1999 impeachment trial of former U.S. president Bill Clinton, some of his defenders committed this fallacy when they argued that an extramarital affair is part of a person’s private life and not a sufficient justification for impeaching a president. However, Clinton’s political opponents maintained that whether the president had an affair was irrelevant: he had lied under oath, an action that in their minds justified impeachment.

Page 557

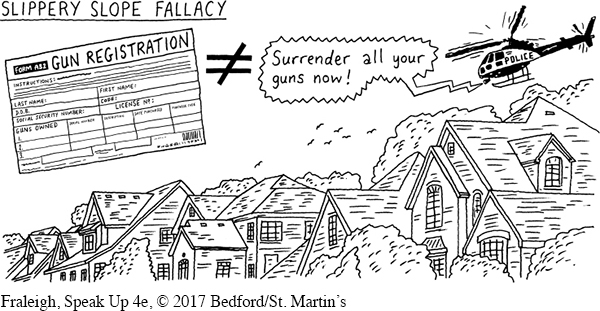

Slippery Slope Fallacy. You’ve fallen victim to the slippery slope fallacy if you argue against a policy because you assume (without proof) that it will lead to a second policy that is undesirable. Like the straw person fallacy, this type of argument distracts the audience from the real issue at hand. Here’s one example of a slippery slope argument during a televised community forum on gun control:

We cannot expand background checks on gun purchases. That would lead us down the road to allowing the federal government to confiscate the guns of law-

In this example, the speaker had no evidence or reasoning to explain how the first policy (background checks on gun purchases) would lead to the second (confiscation of guns from persons who have a legal right to own them).

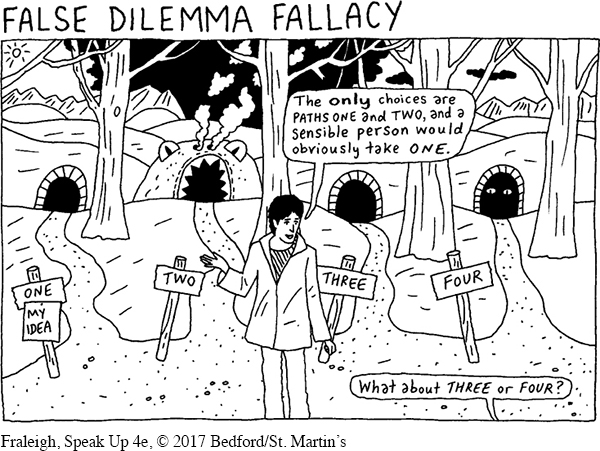

False Dilemma Fallacy. You fall prey to the false dilemma fallacy if you claim that there are only two possible choices to address a problem, that one of those choices is wrong or infeasible, and that therefore your listeners must embrace the other choice. For example:

Page 558

Either you must get an advanced degree immediately after you graduate, or you’ll never find a job in this difficult market.

The weakness in a false dilemma argument is that most problems have more than just two possible solutions. To illustrate, in the previous example, the two options expressed (either pursue a graduate degree or remain jobless) are certainly not the only possibilities. Many people with bachelor’s degrees are able to get jobs, and graduate programs often prefer that their candidates have a few years of real-

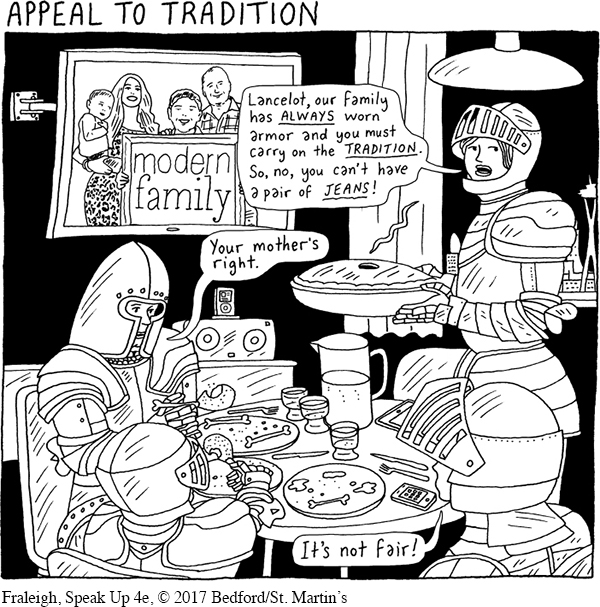

Appeal to Tradition Fallacy. You’ve committed the appeal to tradition fallacy if you argue that an idea or a policy is good simply because people have accepted or followed it for a long time. For example:

We must continue to require general education courses at this college. For the past fifty-

Page 559

This argument is weak because it offers no explanation for why the tradition of general education courses is a good thing in the first place. The fallacy lies in presenting history and tradition as proof that a policy is good. A speaker defending something historic or traditional must show why it is worth preserving. In the previous example, a speaker might support the point by noting the benefits that students gain from taking general education courses (versus taking more classes of their choice or in their major) or the increased career options that students with broad general education backgrounds have after college.

To watch a speaker using a fallacy in his speech, try Video Activity 18.2, “Fallacy: Either-Or (False Dilemma): Diplomacy vs. WWIII (Needs Improvement).”