From Linear to Transactional: Evolving Views of the Public Speaking Process

At the dawn of the modern communication disciplines, scholars viewed all forms of communication—

Page 19

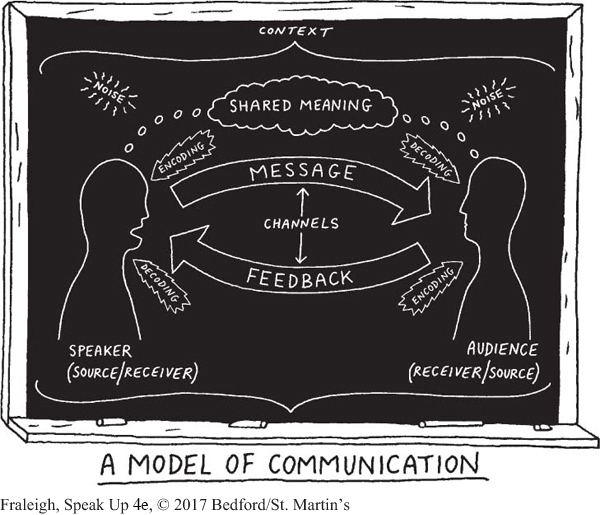

A linear model includes several key elements. Specifically, a person with an idea to express is the source, and the ideas that he or she conveys to the audience constitute the message. The source must encode the message, meaning that he or she chooses verbal and nonverbal symbols to express the ideas. Verbal symbols are the words that the source uses. Nonverbal symbols are the means of making a point without the use of words, such as hand gestures, eye contact, and facial expressions.

The source communicates the encoded message through a channel, the medium of delivery. For example, to deliver their message, speakers can use their voices to address a small group, rely on a microphone or the broadcast airwaves to give a speech to a huge crowd, or even podcast a speech so that it can be heard at different times in different locations.

In the linear model, sources communicate their message to one or more receivers, who try to make sense of the message by decoding. To decode, receivers process the source’s verbal and nonverbal symbols and form their own perception of the message’s meaning.

Noise (also called interference) is a phenomenon that disrupts communication between source and receiver. Noise may be caused by external sources (for example, when a speech is drowned out by a fleet of jets roaring overhead). But noise also can originate internally—

Page 20

Today, scholars have modified this view to consider communication—

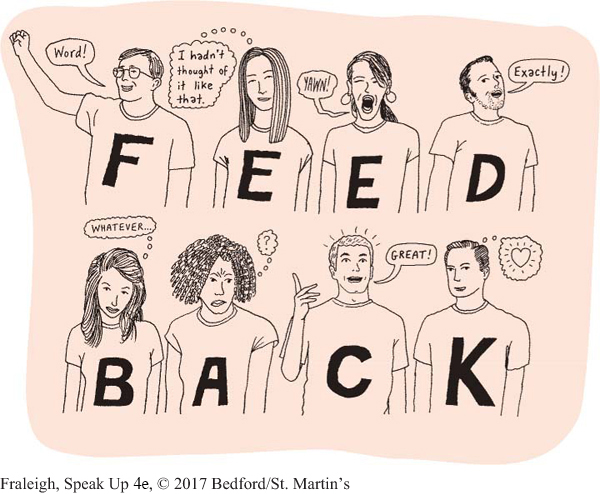

Participants in a public speaking transaction can also send and receive messages by providing feedback in the form of verbal or nonverbal responses. An audience member who shouts “Right on!” in response to a compelling point in a speech is giving feedback. People listening to a speech can also provide nonverbal feedback. For example, an audience member can lean forward to express interest, nod vigorously to show agreement, fold her arms to signal disagreement, or adopt a puzzled look to convey confusion.

Page 21

In the transactional model of communication, the participants in a public speaking exchange seek to create shared meaning—a common understanding with little confusion and few misinterpretations.26 Good public speakers don’t merely try to get their point of view across to their audience. Instead, they strive to improve their own knowledge, seek understanding, and develop agreements when they communicate with others.27

For example, suppose an audience member nods when the speaker says, “We can easily put our privacy at risk on Facebook.” The speaker must assume the role of receiver and decode the message behind that nod. The nod could mean either “I agree” or “Well, duh, we all know that. Move on!” To better decode the message, a speaker may look for additional cues, such as signs of understanding or boredom on the faces of other audience members. Imagine that the speaker determines that the nod conveys agreement that this potential loss of privacy is a serious problem. He or she might respond by saying, “Because we agree that using Facebook can put our privacy at risk, let’s take a look at how we can protect ourselves.” Audience members then smile and nod. Now, audience and speaker have created shared meaning.

Page 22