The Classical Approach to Speech Preparation

The speech preparation process that we outline in this book is based on principles of rhetoric that have been taught and learned for over 2,400 years. As we noted in Chapter 1, Aristotle wrote a systematic analysis of rhetorical practices in the fourth century BCE. Cicero (106–

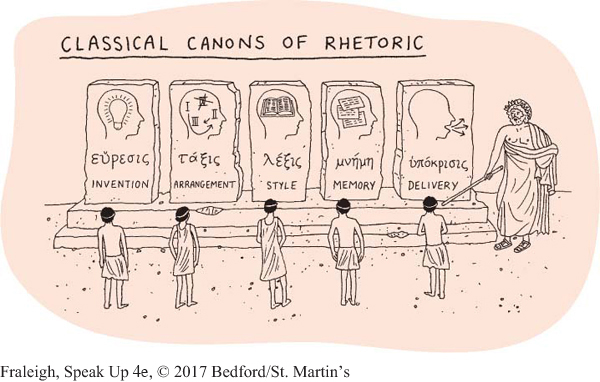

In his treatise De inventione, Cicero maintained that effective speakers attend to five key matters while preparing a speech—

Invention is the generation of ideas for use in a speech, including both the speaker’s own thoughts on the topic and ideas from other sources. Speakers generate a large number of ideas for their speeches and then choose those that will best serve their purpose in an ethical manner. Talented speakers select the best ideas for a particular speech based on their analysis of their audience, their choice of topic and purpose, the research they conduct, and the evidence they gather.

Page 39

Arrangement refers to the structuring of ideas to convey them effectively to an audience; today, we refer to this as organization. Most speeches have three main parts—

an introduction, a body, and a conclusion— with the body serving as the core of the speech and containing the main points. Effective speakers arrange the ideas in the body so that the message will be clear and memorable to the audience. Style is the choice of language that will best express a speaker’s ideas to the audience. Through effective style, speakers state their ideas clearly, make their ideas memorable, and avoid bias.

Memory (also known as preparation) is somewhat analogous to practice and refers to the work that speakers do to remain in command of their material when they present a speech.7 This canon originally emphasized techniques for learning speeches by heart and creating mental stockpiles of words and phrases that speakers could inject into presentations where appropriate.8 In contemporary settings, speakers seldom recite speeches from memory; instead, they rely on notes to remind themselves of key ideas that they can deliver conversationally.

Delivery refers to the speaker’s use of his or her voice and body during the actual presentation of a speech. A strong delivery—

one in which the speaker’s voice, hand gestures, eye contact, and movements are appropriate for the audience and setting— can make a powerful impression. Chapter 13 covers delivery skills in detail.

The five canons—