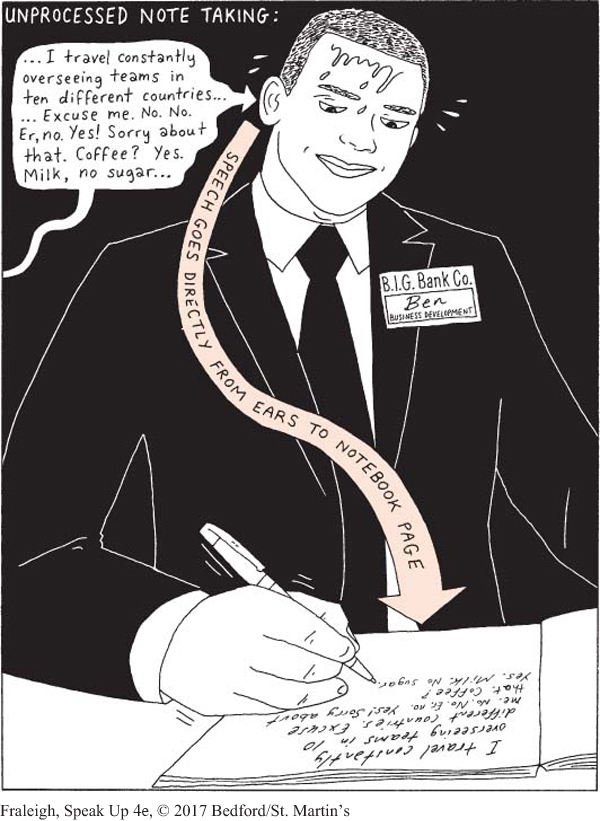

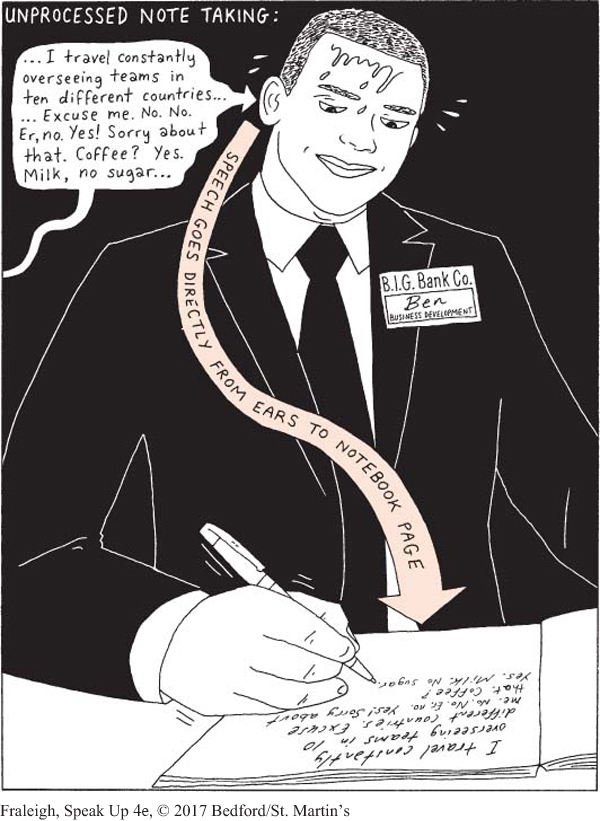

Unprocessed Note Taking

Ben is a former National Football League (NFL) center and now is working for a large national bank. As a business-development officer, he sells the bank’s financial products to wealthy clients. This is his first job after a career in sports, and Ben is aware that a primary reason he was hired was his professional football experience. His manager thinks this background might open doors for him. Ben is very conscientious about keeping an accurate record of what he discusses with each prospective client. When prospects speak in their initial meetings, Ben takes copious notes—often without even looking up. Later, however, Ben finds that he recalls very little of these meetings and has a hard time distinguishing one prospective client from another. Why? Ben is taking in the information, but he is not processing it.

Note taking can be a useful tool at various stages of the speechmaking process—from writing notes while interviewing an expert during the research phase to jotting down key ideas when you’re an audience member. However, note taking can become a problem if you engage in unprocessed note taking—copying the speaker’s words verbatim without considering what you’re writing down. Unprocessed note takers physically hear words, but they don’t listen—that is, actively process and retain them. Instead, the words enter their consciousness and just as quickly exit, deposited in their notebooks or on their laptops—sometimes in incomprehensible form. Unprocessed note takers usually have trouble remembering what was said in an interview, a lecture, or a speech. They also miss opportunities to ask clarifying questions or to comment in informed, thoughtful ways. When you’re taking notes, be sure to focus fully on your interviewee or speaker, processing what she or he is saying and writing down the most important points.

Page 101