Asian Christianity

It was in Arabia, the homeland of Islam, that the decimation of earlier Christian communities occurred most completely and most quickly, for within a century or so of Muhammad’s death in 632, only a few Christian groups remained. During the eighth century, triumphant Muslims marked the replacement of the old religion by using pillars of a demolished Christian cathedral to construct the Grand Mosque of Sana’a in southern Arabia.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, other Jewish and Christian communities soon felt the impact of Islam. When expanding Muslim forces took control of Jerusalem in 638 and subsequently constructed the Muslim shrine known as the Dome of the Rock (687–691), that precise location had long been regarded as sacred. To Jews, it contained the stone on which Abraham prepared to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice to God, and it was the site of the first two Jewish temples. To Christians, it was a place that Jesus had visited as a youngster to converse with learned teachers and later to drive out the moneychangers. Thus, when the Umayyad caliph (successor to the prophet) Abd al-Malik ordered a new construction on that site, he was appropriating for Islam both Jewish and Christian legacies. But he was also demonstrating the victorious arrival of a new faith and announcing to Christians and Jews that “the Islamic state was here to stay.”3

In Syria and Persia with more concentrated populations of Christians, accommodating policies generally prevailed. Certainly Arab conquest of these adjacent areas involved warfare, largely against the military forces of existing Byzantine and Persian authorities, but not to enforce conversion. In both areas, however, the majority of people turned to Islam voluntarily, attracted perhaps by its aura of success. A number of Christian leaders in Syria, Jerusalem, Armenia, and elsewhere negotiated agreements with Muslim authorities whereby remaining Christian communities were guaranteed the right to practice their religion, largely in private, in return for payment of a special tax.

Much depended on the attitudes of local Muslim rulers. On occasion churches were destroyed, villages plundered, fields burned, and Christians forced to wear distinctive clothing. By contrast, a wave of church building took place in Syria under Muslim rule, and Christians were recruited into the administration, schools, translation services, and even the armed forces of the Arab Empire. In 649, only 15 years after Damascus had been conquered by Arab forces, a Nestorian Bishop wrote: “These Arabs fight not against our Christian religion; nay rather they defend our faith, they revere our priests and Saints, and they make gifts to our churches and monasteries.”4

Thus the Nestorian Christian communities of Syria, Iraq, and Persia, sometimes called the Church of the East, survived the assault of Islam, but they did so as shrinking communities of second-class subjects regulated minorities forbidden from propagating their message to Muslims. They also abandoned their religious paintings and sculptures, fearing to offend Muslims, who generally objected to any artistic representation of the Divine.

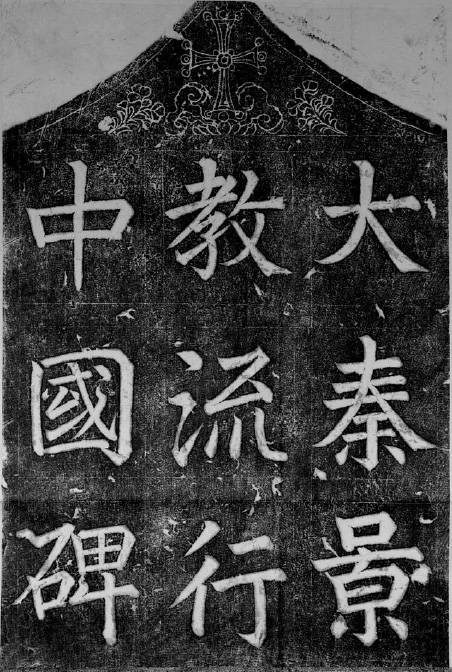

But further east, a small and highly creative Nestorian church, initiated in 635 by a Persian missionary monk, had taken root in China with the approval of the country’s Tang dynasty rulers. Both its art and literature articulated the Christian message using Buddhist and Daoist concepts. The written texts themselves, known as the Jesus Sutras, refer to Christianity as the “Religion of Light from the West” or the “Luminous Religion.” They describe God as the “Cool Wind,” sin as “bad karma,” and a good life as one of “no desire” and “no action.” “People can live only by dwelling in the living breath of God,” the Jesus Sutras declare. “All the Buddhas are moved by this wind, which blows everywhere in the world.”5 The contraction of this remarkable experiment owed little to Islam, but derived rather from the vagaries of Chinese politics. In the mid-ninth century the Chinese state turned against all religions of foreign origin, Islam and Buddhism as well as Christianity (see Chapter 8). Wholly dependent on the goodwill of Chinese authorities, this small outpost of Christianity withered.

Later the Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century offered a brief opportunity for Christianity’s renewal, as the religiously tolerant Mongols welcomed Nestorian Christians as well as various other faiths. A number of prominent Mongols became Christians, including one of the wives of Chinggis Khan. Considering Jesus as a powerful shaman, Mongols also appreciated that Christians, unlike Buddhists, could eat meat and unlike Muslims, could drink alcohol, even including it in their worship.6 But Mongol rule was short, ending in 1368, and the small number of Chinese Christians ensured that the faith almost completely vanished with the advent of the vigorously Confucian Ming dynasty.