The Great Dying

Whatever combination of factors explains the European acquisition of their empires in the Americas, there is no doubting their global significance. Chief among those consequences was the demographic collapse of Native American societies. Although precise figures remain the subject of much debate, scholars generally agree that the pre-Columbian population of the Western Hemisphere was substantial, perhaps 60 to 80 million. The greatest concentrations of people lived in the Mesoamerican and Andean zones, which were dominated by the Aztec and Inca empires. Long isolation from the Afro-Eurasian world and the lack of most domesticated animals meant the absence of acquired immunities to Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, typhus, influenza, malaria, and yellow fever.

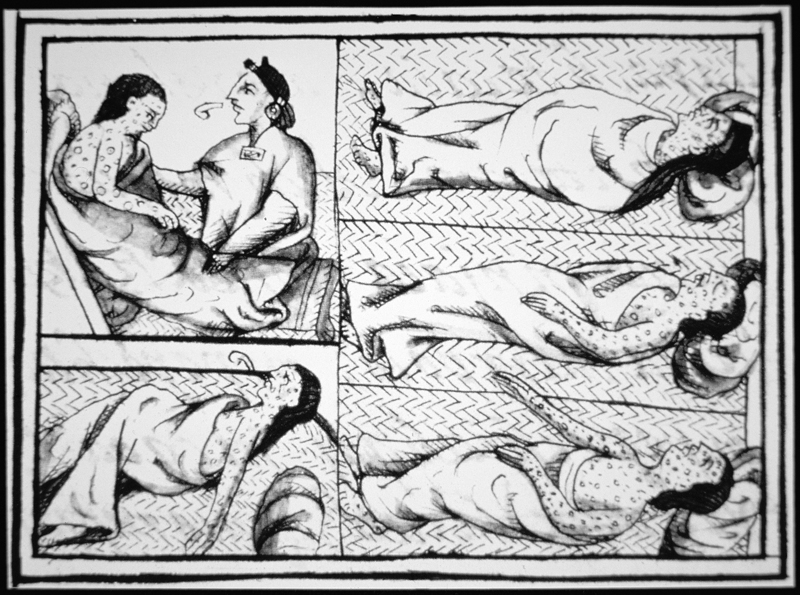

Therefore, when they came into contact with these European and African diseases, Native American peoples died in appalling numbers, in many cases up to 90 percent of the population. The densely settled peoples of Caribbean islands virtually vanished within fifty years of Columbus’s arrival. Central Mexico, with a population estimated at some 10 to 20 million, declined to about 1 million by 1650. A native Nahuatl (nah-watl) account depicted the social breakdown that accompanied the smallpox pandemic: “A great many died from this plague, and many others died of hunger. They could not get up to search for food, and everyone else was too sick to care for them, so they starved to death in their beds.”5

The situation was similar in North America. A Dutch observer in New Netherland (later New York) reported in 1656 that “the Indians . . . affirm that before the arrival of the Christians, and before the small pox broke out amongst them, they were ten times as numerous as they are now, and that their population had been melted down by this disease, whereof nine-tenths of them have died.”6 To Governor Bradford of Plymouth colony (in present-day Massachusetts), such conditions represented the “good hand of God” at work, “sweeping away great multitudes of the natives . . . that he might make room for us.”7 Not until the late seventeenth century did native numbers begin to recuperate somewhat from this catastrophe, and even then not everywhere.