Introduction

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Revolutions of Industrialization

1750–1914

“Industrialization is, I am afraid, going to be a curse for mankind. . . . God forbid that India should ever take to industrialism after the manner of the West. The economic imperialism of a single tiny island kingdom (England) is today [1928] keeping the world in chains. If an entire nation of 300 millions took to similar economic exploitation, it would strip the world bare like locusts. . . . Industrialization on a mass scale will necessarily lead to passive or active exploitation of the villagers. . . . The machine produces much too fast.”1

Such were the views of the famous Indian nationalist and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi, who subsequently led his country to independence from British colonial rule by 1947, only to be assassinated a few months later. However, few people anywhere have agreed with India’s heroic figure. Since its beginning in Great Britain in the late eighteenth century, the idea of industrialization, if not always its reality, has been embraced in every kind of society, both for the wealth it generates and for the power it conveys. Even Gandhi’s own country, once it achieved its independence, largely abandoned its founding father’s vision of small-scale, village-based handicraft manufacturing in favor of modern industry. As the twenty-first century dawned, India was moving rapidly to develop a major high-technology industrial sector. At that time, across the river from the site in New Delhi where Gandhi was cremated in 1948, a large power plant belched black smoke.

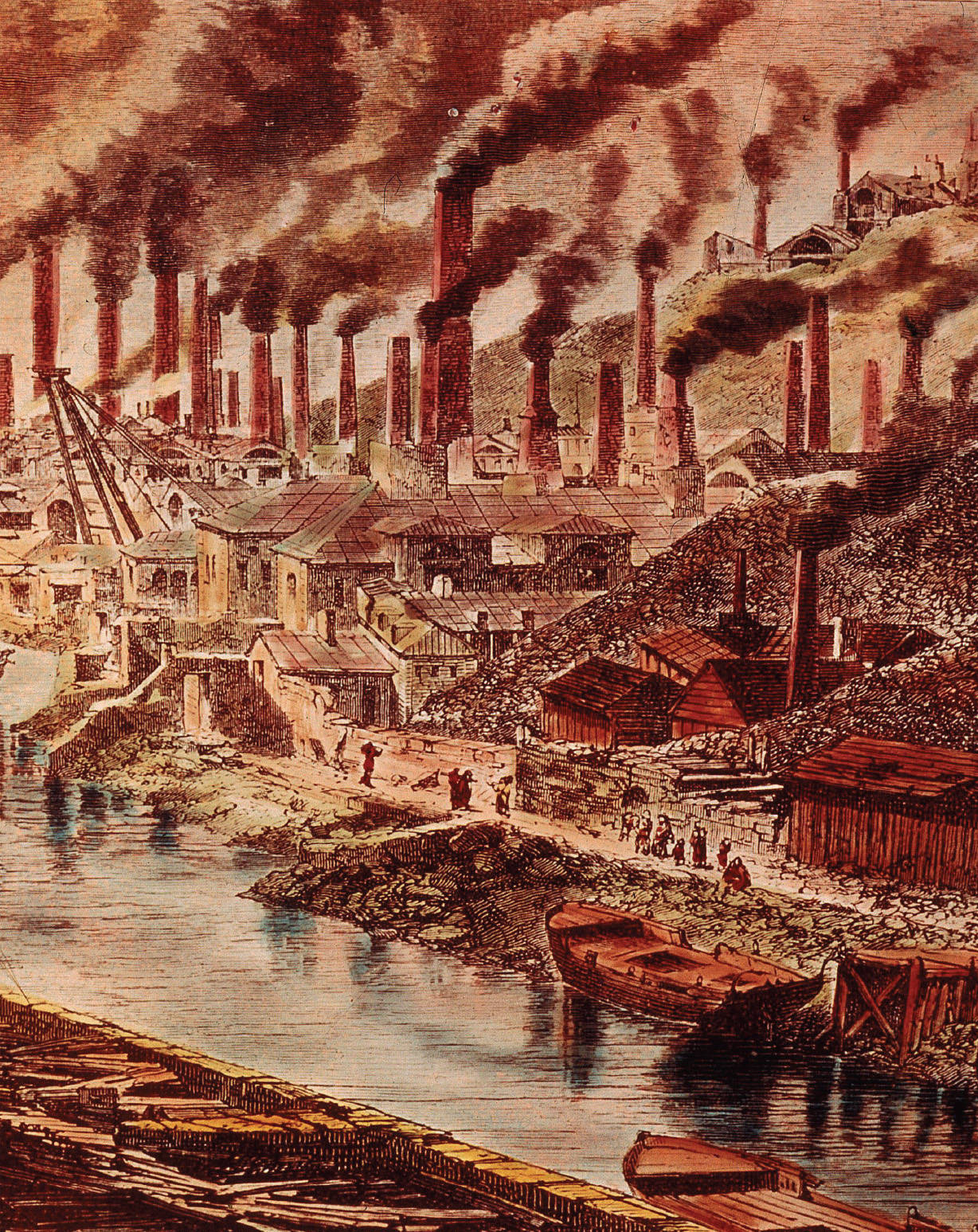

NO ELEMENT OF EUROPE’S MODERN TRANSFORMATION HELD A GREATER SIGNIFICANCE for the history of humankind than the Industrial Revolution, which took place initially in the century and a half between 1750 and 1900. It drew on the Scientific Revolution and accompanied the unfolding legacy of the French Revolution to utterly transform European society and to propel Europe into a temporary position of global dominance. Not since the breakthrough of the Agricultural Revolution some 12,000 years ago had human ways of life been so fundamentally altered. But the Industrial Revolution, unlike its agricultural predecessor, began independently in only one place, Western Europe, and more specifically Great Britain. From there, it spread much more rapidly than agriculture, though very unevenly, to achieve a worldwide presence in less than 250 years. Far more than Christianity, democracy, or capitalism, Europe’s Industrial Revolution has been enthusiastically welcomed virtually everywhere.

SEEKING THE MAIN POINT

In what ways did the Industrial Revolution mark a sharp break with the past? In what ways did it continue earlier patterns?

In any long-term reckoning, the history of industrialization is very much an unfinished story. It is hard to know whether we are at the beginning of a movement leading to worldwide industrialization, stuck in the middle of a world permanently divided into rich and poor countries, or approaching the end of an environmentally unsustainable industrial era. Whatever the future holds, this chapter focuses on the early stages of an immense transformation in the global condition of humankind.

A Map of Time

| 1712 | Early steam engine in Britain |

| 1780s | Beginning of British Industrial Revolution |

| 1812 | Locomotives first used to haul coal in England |

| 1832 | Reform Bill gave vote to middle-class men in England |

| 1848 | Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto |

| 1850s | Beginning of railroad building in Argentina, Cuba, Chile, Brazil |

| 1861 | Freeing of serfs in Russia |

| 1864–1876 | First International socialist organization in Europe |

| After 1865 | Rapid growth of U.S. industrialization |

| After 1868 | Take-off of Japanese industrialization |

| 1869 | Opening of transcontinental railroad across United States |

| 1871 | Unification of Germany |

| 1889–1916 | Second International socialist organization in Europe |

| 1890s | Rapid growth of Russian industrialization |

| 1891–1916 | Building of trans-Siberian railroad |

| 1905 | Failed revolution in Russia |

| 1910–1920 | Mexican Revolution |

| 1917 | Russian Revolution |