Why Britain?

Comparison

Question

What was distinctive about Britain that may help to explain its status as the breakthrough point of the Industrial Revolution?

[Answer Question]

If the Industrial Revolution was initially a Western European phenomenon generally, it clearly began in Britain in particular. The world’s first Industrial Revolution unfolded spontaneously in a country that concentrated some of the more general features of European society. It was both unplanned and unexpected.

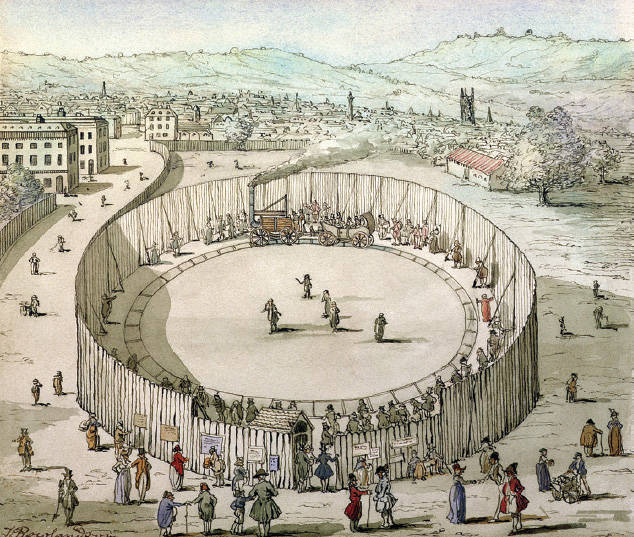

With substantial imperial possessions in the Caribbean, in North America, and, by the late eighteenth century, in India as well, Britain was the most highly commercialized of Europe’s larger countries. Its landlords had long ago “enclosed” much agricultural land, pushing out the small farmers and producing for the market. A series of agricultural innovations—crop rotation, selective breeding of animals, lighter plows, higher-yielding seeds—increased agricultural output, kept food prices low, and freed up labor from the countryside. The guilds, which earlier had protected Britain’s urban artisans, had largely disappeared by the eighteenth century, allowing employers to run their manufacturing enterprises as they saw fit. Coupled with a rapidly growing population, these processes ensured a ready supply of industrial workers who had few alternatives available to them. Furthermore, British aristocrats, unlike their counterparts in Europe, had long been interested in the world of business, and some took part in new mining and manufacturing enterprises. British commerce, moreover, extended around the world, its large merchant fleet protected by the Royal Navy. The wealth of empire and global commerce, however, were not themselves sufficient for spawning the Industrial Revolution, for Spain, the earliest beneficiary of American wealth, was one of the slowest industrializing European countries into the twentieth century.

British political life encouraged commercialization and economic innovation. Its policy of religious toleration, formally established in 1688, welcomed people with technical skills regardless of their faith, whereas France’s persecution of its Protestant minority had chased out some of its most skilled workers. The British government favored men of business with tariffs that kept out cheap Indian textiles, with laws that made it easy to form companies and to forbid workers’ unions, with roads and canals that helped create a unified internal market, and with patent laws that served to protect the interests of inventors. Checks on royal authority—trial by jury and the growing authority of Parliament, for example—provided a freer arena for private enterprise than elsewhere in Europe.

Europe’s Scientific Revolution also took a distinctive form in Great Britain in ways that fostered technological innovation.14 Whereas science on the continent was largely based on logic, deduction, and mathematical reasoning, in Britain it was much more concerned with observation, experiment, precise measurements, mechanical devices, and practical commercial applications. Discoveries about atmospheric pressure and vacuums, for example, played an important role in the invention and improvement of the steam engine. Even though most inventors were artisans or craftsmen rather than scientists, in eighteenth-century Britain they were in close contact with scientists, makers of scientific instruments, and entrepreneurs, whereas in continental Europe these groups were largely separate. The British Royal Society, an association of “natural philosophers” (scientists) established in 1660, saw its role as one of promoting “useful knowledge.” To this end, it established “mechanics’ libraries,” published broadsheets and pamphlets on recent scientific advances, and held frequent public lectures and demonstrations. The integration of science and technology became widespread and permanent after 1850, but for a century before, it was largely a British phenomenon.

Finally, several accidents of geography and history contributed something to Britain’s Industrial Revolution. The country had a ready supply of coal and iron ore, often located close to each other and within easy reach of major industrial centers. Although Britain took part in the wars against Napoleon, the country’s island location protected it from the kind of invasions that so many continental European states experienced during the era of the French Revolution. Moreover, Britain’s relatively fluid society allowed for adjustments in the face of social changes without widespread revolution. By the time the dust settled from the immense disturbance of the French Revolution, Britain was well on its way to becoming the world’s first industrial society.