Economies of Coercion: Forced Labor and the Power of the State

Connection

Question

How did the policies of colonial states change the economic lives of their subjects?

[Answer Question]

Many of the new ways of working that emerged during the colonial era derived directly from the demands of the colonial state. The most obvious was required and unpaid labor on public projects, such as building railroads, constructing government buildings, and transporting goods. In French Africa, all “natives” were legally obligated for “statute labor” of ten to twelve days a year, a practice that lasted through 1946. It was much resented. A resident of British West Africa, interviewed in 1996, bitterly recalled this feature of colonial life: “They [British officials] were rude, and they made us work for them a lot. They came to the village and just rounded us up and made us go off and clear the road or carry loads on our heads.”12

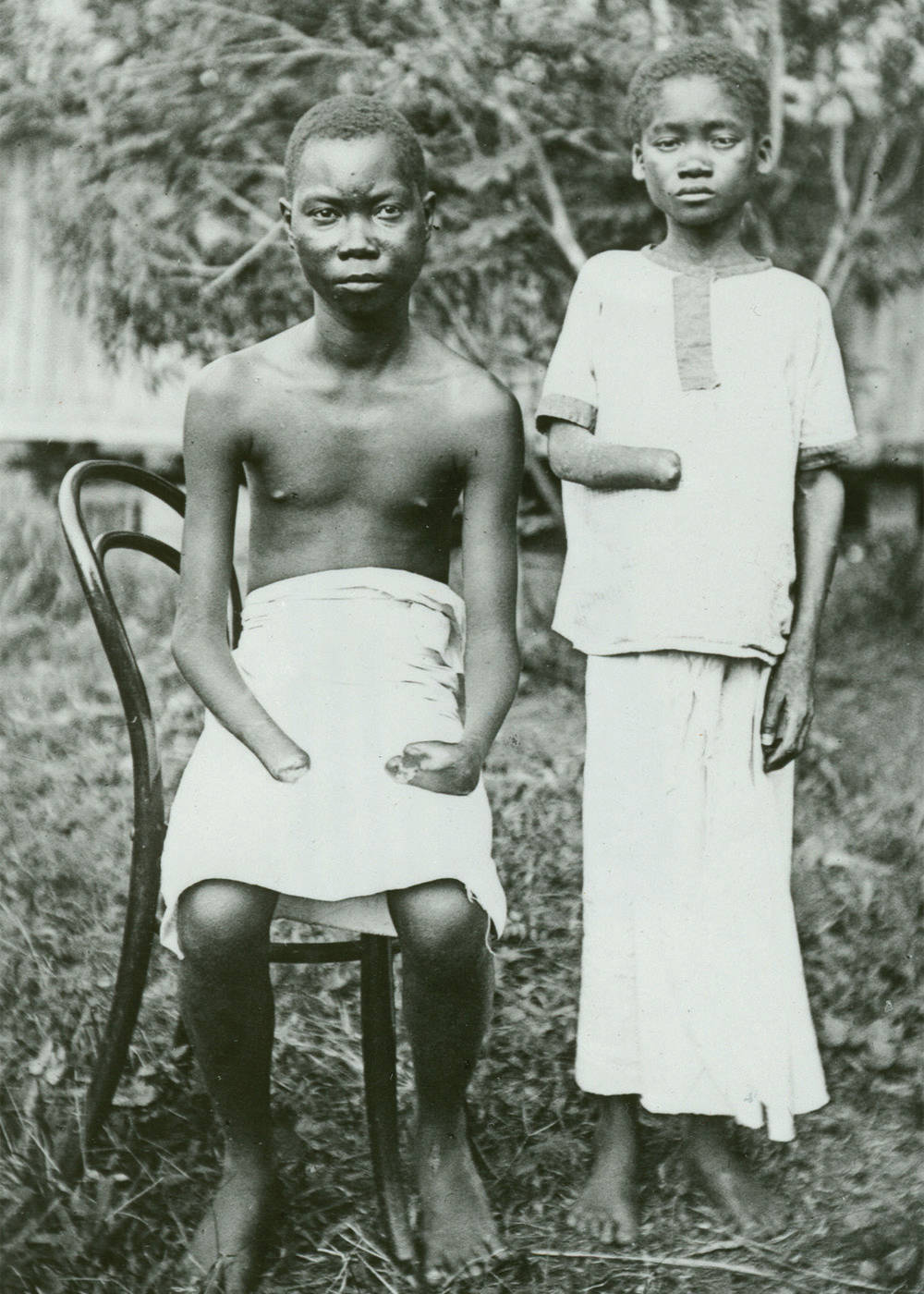

The most infamous cruelties of forced labor occurred during the early twentieth century in the Congo Free State, then governed personally by King Leopold II of Belgium. Private companies in the Congo, operating under the authority of the state, forced villagers to collect rubber, which was much in demand for bicycle and automobile tires, with a reign of terror and abuse that cost millions of lives. One refugee from these horrors described the process:

We were always in the forest to find the rubber vines, to go without food, and our women had to give up cultivating the fields and gardens. Then we starved. . . . We begged the white man to leave us alone, saying we could get no more rubber, but the white men and their soldiers said “Go. You are only beasts yourselves. . . .” When we failed and our rubber was short, the soldiers came to our towns and killed us. Many were shot, some had their ears cut off; others were tied up with ropes round their necks and taken away.13

Eventually such outrages were widely publicized in Europe, where they created a scandal, forcing the Belgian government to take control of the Congo in 1908 and ending Leopold’s reign of terror.

Meanwhile, however, this late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century commerce in rubber and ivory, made possible by the massive use of forced labor in both the Congo and the neighboring German colony of Cameroon, laid the foundations for the modern AIDS epidemic. It was in southeastern Cameroon that the virus causing AIDS made the jump from chimpanzees to humans, and it was in the crowded and hectic Congolese city of Kinshasa, with its new networks of sexual interaction, where that disease found its initial break-out point, becoming an epidemic. “Without the scramble [for Africa],” concludes a recent account, “it’s hard to see how HIV could have made it out of southeastern Cameroon to eventually kills tens of millions of people.”14

A variation on the theme of forced labor took shape in the so-called cultivation system of the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia) during the nineteenth century. Peasants were required to cultivate 20 percent or more of their land in cash crops such as sugar or coffee to meet their tax obligation to the state. Sold to government contractors at fixed and low prices, those crops, when resold on the world market, proved highly profitable for Dutch traders and shippers as well as for the Dutch state and its citizens. According to one scholar, the cultivation system “performed a miracle for the Dutch economy,” enabling it to avoid taxing its own people and providing capital for its Industrial Revolution.15 It also enriched and strengthened the position of those “traditional authorities” who enforced the system, often by using lashings and various tortures, on behalf of the Dutch. For the peasants of Java, however, it meant a double burden of obligations to the colonial state as well as to local lords. Many became indebted to moneylenders when they could not meet those obligations. Those demands, coupled with the loss of land and labor now excluded from food production, contributed to a wave of famines during the mid-nineteenth century in which hundreds of thousands perished.

The forced cultivation of cash crops was widely and successfully resisted in many places. In German East Africa, for example, colonial authorities in the late nineteenth century imposed the cultivation of cotton, which seriously interfered with production of local food crops. Here is how one man remembered the experience:

The cultivation of cotton was done by turns. Every village was allotted days on which to cultivate. . . . After arriving you all suffered very greatly. Your back and your buttocks were whipped and there was no rising up once you stooped to dig. . . . And yet he [the German] wanted us to pay him tax. Were we not human beings?16

Such conditions prompted a massive rebellion in 1905 and persuaded the Germans to end the forced growing of cotton. In Mozambique, where the Portuguese likewise brutally enforced cotton cultivation, a combination of peasant sabotage, the planting of unauthorized crops, and the smuggling of cotton across the border to more profitable markets ensured that Portugal never achieved its goal of becoming self-sufficient in cotton production. Thus, the actions of colonized peoples could alter or frustrate the plans of the colonizers.