Visual Source 19.4

Japan, China, and Europe

Behind Japan’s modernization and Westernization was the recognition that Western imperialism was surging in Asia and that China was a prime example of what happened to countries unable to defend themselves against it. Accordingly, achieving political and military equality with the Great Powers of Europe and the United States became a central aim of Japan’s modernization program.

Strengthening Japan against Western aggression increasingly meant “throwing off Asia,” a phrase that implied rejecting many of Japan’s own cultural traditions and its habit of imitating China as well as creating an Asian empire of its own. Fukuzawa Yukichi, a popular advocate of Western knowledge, declared:

We must not wait for neighboring countries to become civilized so that we can together promote Asia’s revival. Rather we should leave their ranks and join forces with the civilized countries of the West. We don’t have to give China and Korea any special treatment just because they are neighboring countries. We should deal with them as Western people do. Those who have bad friends cannot avoid having a bad reputation. I reject the idea that we must continue to associate with bad friends in East Asia.21

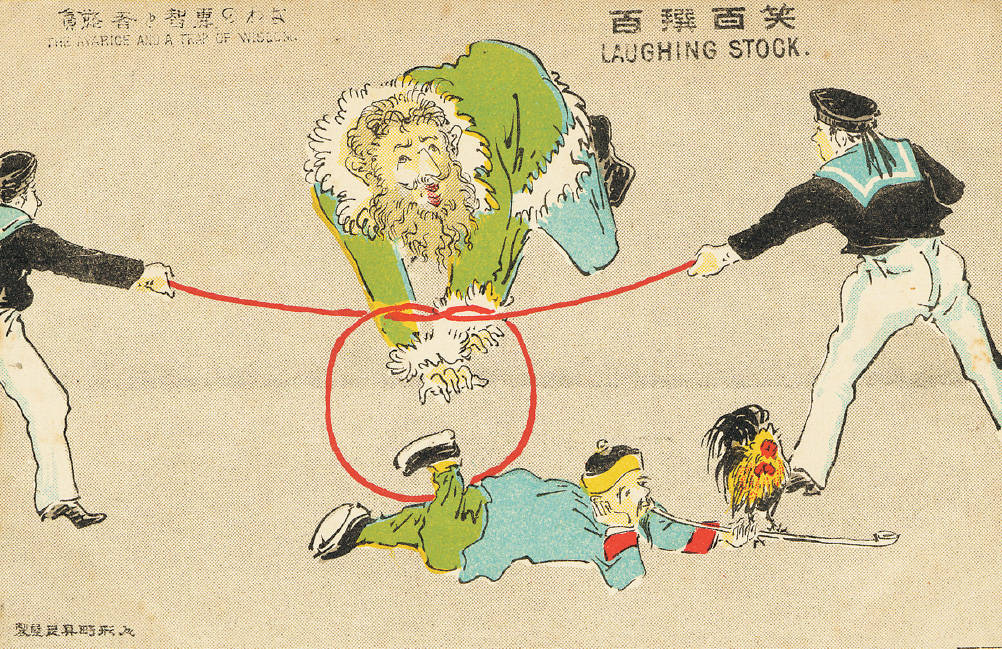

Historically the Japanese had borrowed a great deal from China—Buddhism, Confucianism, court rituals, city-planning ideas, administrative traditions, and elements of the Chinese script. But Japan’s victory in a war with China in 1894–1895 showed clearly that it had thrown off the country in whose cultural shadow it had lived for centuries. Furthermore, Japan had begun to acquire an East Asian empire in Korea and Taiwan. And its triumph over Russia in another war ten years later illustrated its ability to stand up to a major European power. The significance of these twin victories is expressed in Visual Source 19.4, a Japanese image created during the Russo-Japanese War and titled The Japanese Navy Uses China as Bait to Trap the Greedy Russian.

Question

What overall message did the artist seek to convey in this print?

Question

What is the significance of the Chinese figure with a chicken in hand, lying as “bait” at the bottom of the image?

Question

How is the Russia character portrayed?

Question

What had changed in Japanese thinking about China and Europe during the nineteenth century?