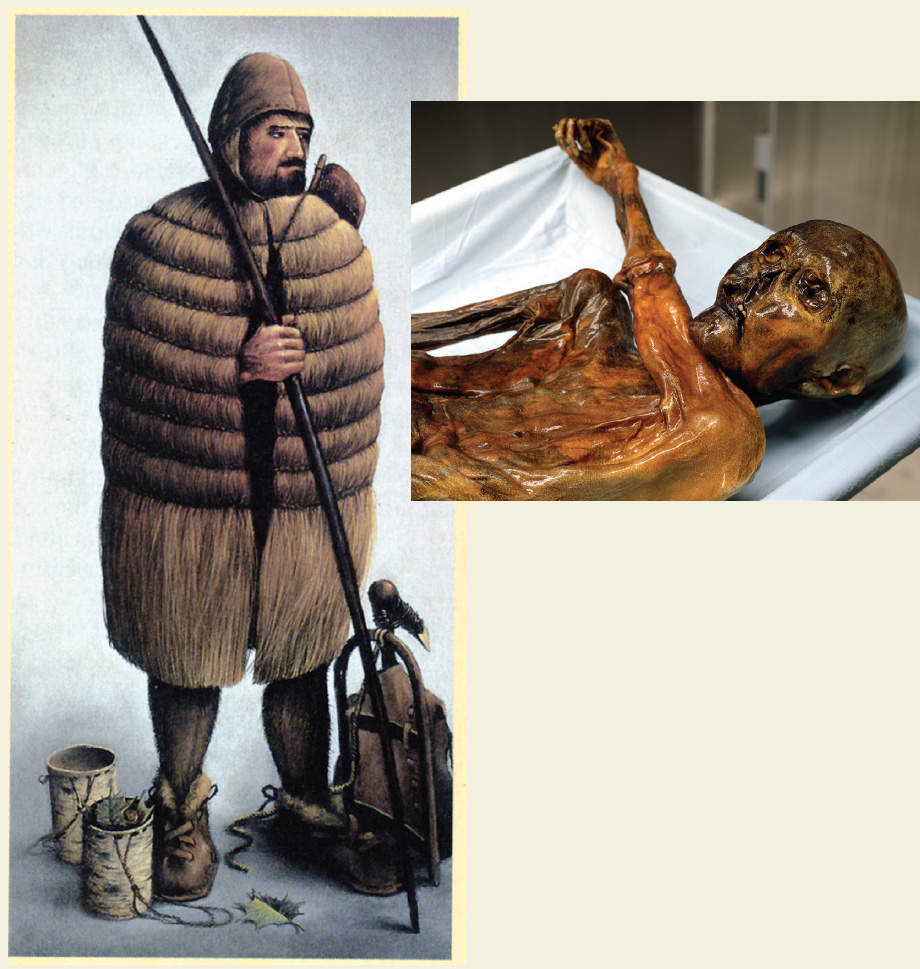

Visual Source 1.3

Otzi the Iceman

Beyond the artistic products of people without writing, historians have also learned much from their burial sites. Analysis of human remains often discloses something about diet, nutrition, and disease, while variations in burial materials can provide indications of social status, technology, religion, and more. Among the more famous burials of the Neolithic era was that of Otzi the Iceman, a forty-six-year-old man, about 5’5” tall, whose body was discovered in 1991 frozen in a glacier high in the Italian Alps. Properly speaking, it was not a burial at all, for Otzi, named for the region in which he was found, died far from home about 5,300 years ago in this remote mountainous area, his body left to the elements, which miraculously preserved it for over five millennia.

In his mid-forties, Otzi was an old man for his time and place, no doubt full of aches and pains. The condition of his bones and evidence of frostbite suggest that he spent much of his life in steep, cold mountainous terrain. Some fifty-seven tattoos, made by small incisions into which charcoal was rubbed, probably reflect treatments for pain relief. Traces of arsenic in his hair indicate that he was exposed to the smelting of copper. His last meals included wild goat and deer meat as well as threshed and processed wheat, perhaps in the form of bread, which suggests that he lived in an agricultural community. A gash in his hand points to hand-to-hand fighting not long before his death; a flint arrow that lodged in his back and severed an artery, as well as evidence of a blow to his head, show that Otzi did not die a natural death but was killed. His attacker appears to have then pulled out the shaft of the arrow, perhaps fearing it could identify him, for no such shaft was found among his remains. So we know how Otzi died, but not why. Even so, it is about as close as we get to a particular event in history before writing.

Materials accompanying his body fill out the picture of his life. His clothing consisted of a leather loincloth and leggings, a coat of stitched animal furs, and covering all of this, a cape of woven grass. A belt, a bearskin cap, and waterproof shoes made of bearskin and deer hide and stuffed with grass as insulation completed his outfit. An ax with a copper blade reveals that Otzi was living at the beginning of the age of metals, while stone scrappers and a flint knife indicate continued reliance on an earlier technology. He was well provisioned for a substantial journey with several small baskets, a birch bark drinking cup, several dried mushrooms, replacement materials of leather straps and sinew, a drill and a tool for sharpening flint blades, a six-foot bow and a quiver full of arrows, and a wood-framed backpack. We know that Otzi was far from his home, probably located considerably to the south of the Alpine mountain chain where he died, but no one knows why he chose to go there. Was he a shepherd herding his flock, part of an armed party involved in a skirmish with enemies, or a solitary traveler attacked by local people?

Visual Source 1.3 shows an artist’s reconstruction of the Iceman and some of his accompanying materials, while the small insert shows the actual head and torso of his preserved body.

Question

What elements of the above description are visible in the reconstructed drawing?

Question

Do you think that the inferences about his life made by scholars are justified based on the evidence available?

Question

Create a story that takes account of what is known about Otzi, while imaginatively fleshing out something of his life and death. What additional archeological evidence would be useful in doing so?