Into the Pacific

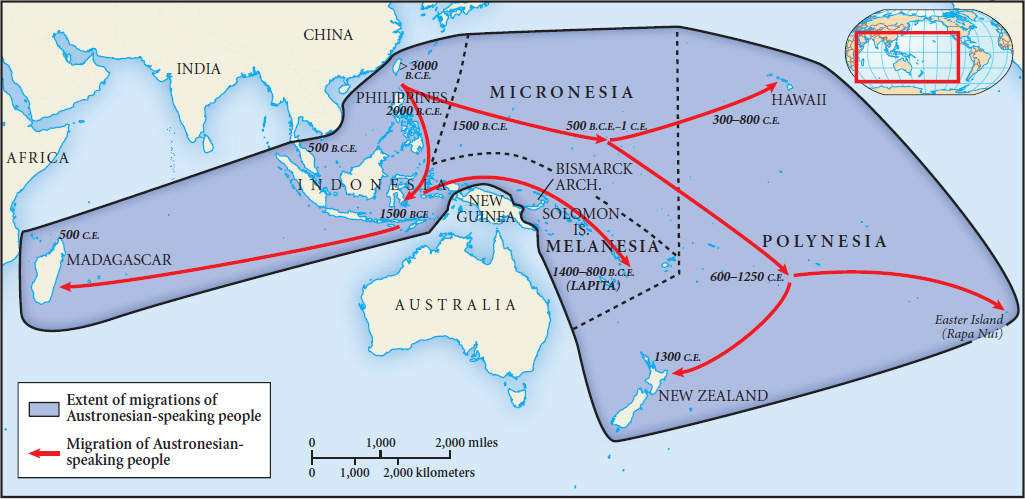

The last phase of the great human migration to the ends of the earth took place in the Pacific Ocean and was distinctive in many ways. In the first place, it occurred quite recently, jumping off only about 3,500 years ago from the Bismarck and Solomon Islands near New Guinea as well as from the islands of the Philippines. It was everywhere a waterborne migration, making use of oceangoing canoes and remarkable navigational skills, and it happened very quickly and over a huge area of the planet. Speaking Austronesian languages that trace back to southern China, these oceanic voyagers had settled every habitable piece of land in the Pacific basin within about 2,500 years. Other Austronesians had sailed west from Indonesia across the Indian Ocean to settle the island of Madagascar off the coast of eastern Africa. This extraordinary process of expansion made the Austronesian family of languages the most geographically widespread in the world and their trading networks, reaching some 5,000 miles from western Indonesia to the mid-Pacific, the most extensive. With the occupation of Aotearoa (New Zealand) around 1000 to 1300 C.E., the initial human settlement of the planet was finally complete (see Map 1.2).

Comparison

Question

How did Austronesian migrations differ from other early patterns of human movement?

[Answer Question]

In contrast with all of the other initial migrations, these Pacific voyages were undertaken by agricultural people who carried both domesticated plants and animals in their canoes. Both men and women made these journeys, suggesting a deliberate intention to colonize new lands. Virtually everywhere they went, two developments followed. One was the creation of highly stratified societies or chiefdoms, of which ancient Hawaiian society is a prime example. In Hawaii, an elite class of chiefs with political and military power ruled over a mass of commoners. The other development involved the quick extinction of many species of animals, especially large flightless birds such as the moa of New Zealand, which largely vanished within a century of human arrival. On Rapa Nui (Easter Island) between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries C.E., deforestation accompanied famine, violent conflict, and a sharp population decline in this small island society, while the elimination of large trees ensured that no one could leave the island, for they could no longer build the canoes that had brought them there.6