Capitalism Unraveling: The Great Depression

Connection

Question

In what ways was the Great Depression a global phenomenon?

[Answer Question]

Far and away the most influential change of the postwar decades lay in the Great Depression. If World War I represented the political collapse of Europe, this catastrophic downturn suggested that Western capitalism was likewise failing. During the nineteenth century, that economic system had spurred the most substantial economic growth in world history and had raised the living standards of millions, but to many people it was a troubling system. Its very success generated an individualistic materialism that seemed to conflict with older values of community and spiritual life. To socialists and many others, its immense social inequalities were unacceptable. Furthermore, its evident instability—with cycles of boom and bust, expansion and recession—generated profound anxiety and threatened the livelihood of both industrial workers and those who had gained a modest toehold in the middle class.

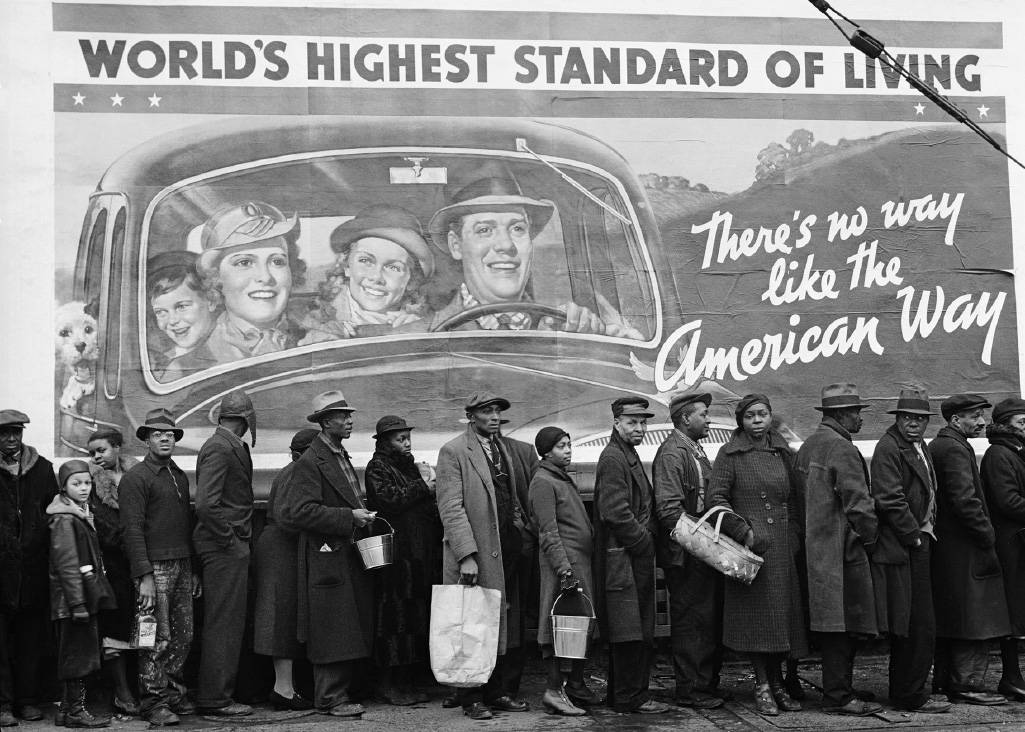

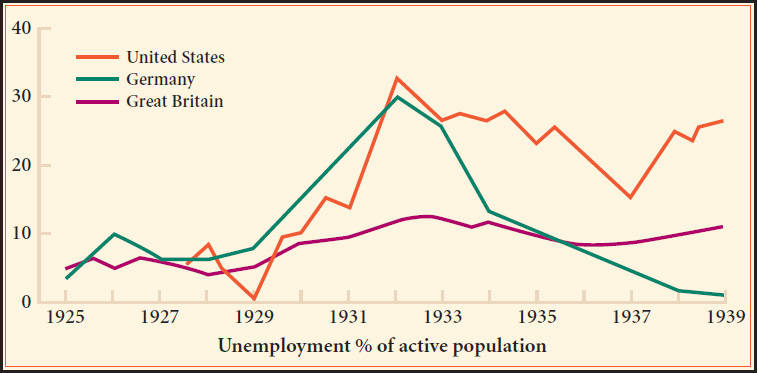

Never had the flaws of capitalism been so evident or so devastating as during the decade that followed the outbreak of the Great Depression in 1929. All across the Euro-American heartland of the capitalist world, this vaunted economic system seemed to unravel. For the rich, it meant contracting stock prices that wiped out paper fortunes almost overnight. On the day that the American stock market initially crashed (October 24, 1929), eleven Wall Street financiers committed suicide, some by jumping out of skyscrapers. Banks closed, and many people lost their life savings. Investment dried up, world trade dropped by 62 percent within a few years, and businesses contracted when they were unable to sell their products. For ordinary people, the worst feature of the Great Depression was the loss of work. Unemployment soared everywhere, and in both Germany and the United States it reached 30 percent or more by 1932 (see the Snapshot). Vacant factories, soup kitchens, bread lines, shantytowns, and beggars came to symbolize the human reality of this economic disaster.

Explaining its onset, its spread from America to Europe and beyond, and its continuation for a decade has been a complicated task for historians. Part of the story lies in the United States’ booming economy during the 1920s. In a country physically untouched by the Great War, wartime demand had greatly stimulated agricultural and industrial capacity. By the end of the 1920s, its farms and factories were producing more goods than could be sold because a highly unequal distribution of income meant that many people could not afford to buy the products that American factories were churning out. Nor were major European countries able to purchase those goods. Germany and Austria had to make huge reparation payments and were able to do so only with extensive U.S. loans. Britain and France, which were much indebted to the United States, depended on those reparations to repay their loans. Furthermore, Europeans generally had recovered enough to begin producing some of their own goods, and their expanding production further reduced the demand for American products. Meanwhile, a speculative stock market frenzy had driven up stock prices to an unsustainable level. When that bubble burst in late 1929, this intricately connected and fragile economic network across the Atlantic collapsed like a house of cards.

Much as Europe’s worldwide empires had globalized the Great War, so too its economic linkages globalized the Great Depression. Countries or colonies tied to exporting one or two products were especially hard-hit. Colonial Southeast Asia, the world’s major rubber-producing region, saw the demand for its primary export drop dramatically as automobile sales in Europe and the United States were cut in half. In Britain’s West African colony of the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), farmers who had staked their economic lives on producing cocoa for the world market were badly hurt by the collapse of commodity prices. Latin American countries, whose economies were based on the export of agricultural products and raw materials, were also vulnerable to major fluctuations in the world market. The region as a whole saw the value of its exports cut by half during the Great Depression. In an effort to maintain the price of coffee, Brazil destroyed enough of its crop to have supplied the world for a year. Such conditions led to widespread unemployment and social tensions.

Those tensions of the Depression era often found political expression in Latin America in the form of a military takeover of the state. Such governments sought to steer their countries away from an earlier dependence on exports toward a policy of generating their own industries. Known as import substitution industrialization, such policies hoped to achieve greater economic independence by manufacturing for the domestic market goods that had previously been imported. These efforts were accompanied by more authoritarian and intrusive governments that played a greater role in the economy by enacting tariffs, setting up state-run industries, and favoring local businesses. They often adopted a highly nationalist and populist posture as they sought to extricate themselves from economic domination by the United States and Europe and to respond to the growing urban classes of workers and entrepreneurs.

In Brazil, for example, the Depression discredited the established export elites such as coffee growers and led to the dictatorship of Getulio Vargas (1930–1945). Supported by the military, his government took steps to modernize the urban industrial sector of the economy including a state enterprise to manufacture trucks and airplane engines and regulations that gave the state considerable power over both unions and employers. But little was done to alleviate rural poverty. In Mexico, the Depression opened the way to a revival of the principles of the Mexican Revolution under the leadership of Lazaro Cardenas (1934–1940). He pushed land reform, favored Mexican workers against foreign interests, and nationalized an oil industry dominated by American capital.

These were but two cases of the many political and economic changes stimulated in Latin America by the Great Depression. Many of those changes—the growing role of the army in politics; authoritarian, populist, and interventionist governments; import substitution industrialization; and the assumption that governments should improve economic life—persisted in the decades that followed.

The Great Depression also sharply challenged the governments of industrialized capitalist countries, which generally had believed that the economy would regulate itself through the market. The market’s apparent failure to self-correct led many people to look twice at the Soviet Union, the communist state that grew out of the Russian Revolution and encompassed much of the territory of the old Russian Empire (see The Steppes and Siberia: The Making of a Russian Empire). There, the dispossession of the propertied classes and a state-controlled economy had generated an impressive economic growth with almost no unemployment in the 1930s, even as the capitalist world was reeling. No Western country opted for the dictatorial and draconian socialism of the Soviet Union, but in Britain, France, and Scandinavia, the Depression energized a “democratic socialism” that sought greater regulation of the economy and a more equal distribution of wealth through peaceful means and electoral politics.

The United States’ response to the Great Depression came in the form of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal (1933–1942), an experimental combination of reforms seeking to restart economic growth and to prevent similar calamities in the future. These measures reflected the thinking of John Maynard Keynes, a prominent British economist who argued that government actions and spending programs could moderate the recessions and depressions to which capitalist economies were prone. Although this represented a departure from standard economic thinking, none of it was really “socialist,” even if some of the New Deal’s opponents labeled it as such.

Nonetheless, Roosevelt’s efforts permanently altered the relationship among government, the private economy, and individual citizens. Through immediate programs of public spending (for dams, highways, bridges, and parks), the New Deal sought to prime the pump of the economy and thus reduce unemployment. The New Deal’s longer-term reforms, such as the Social Security system, the minimum wage, and various relief and welfare programs, attempted to create a modest economic safety net to sustain the poor, the unemployed, and the elderly. By supporting labor unions, the New Deal strengthened workers in their struggles with business owners or managers. Subsidies for farmers gave rise to a permanent agribusiness that encouraged continued production even as prices fell. Finally, a mounting number of government agencies marked a new degree of federal regulation and supervision of the economy.

Ultimately, none of the New Deal’s programs worked very well to end the Great Depression. Not until the massive government spending required by World War II kicked in did that economic disaster abate in the United States. The most successful efforts to cope with the Depression came from unlikely places—Nazi Germany and an increasingly militaristic Japan.

Snapshot Comparing the Impact of the Depression3

| As industrial production dropped during the Depression, unemployment soared. Yet the larger Western capitalist countries differed considerably in the duration and extent of this unemployment. Note especially the differences between Germany and the United States. How might you account for this difference? |

|