The Case of India: Ending British Rule

Comparison

Question

How did India’s nationalist movement change over time?

[Answer Question]

Surrounded by the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean, the South Asian peninsula, commonly known as India, enjoyed a certain geographic unity. But before the twentieth century few of its people thought of themselves as “Indians.” Cultural identities were primarily local and infinitely varied, rooted in differences of family, caste, village, language, region, tribe, and religious practice. In earlier centuries—during the Mauryan, Gupta, and Mughal empires, for example—large areas of the subcontinent had been temporarily enclosed within a single political system, but always these were imperial overlays, constructed on top of enormously diverse Indian societies.

So too was British colonial rule, but the British differed from earlier invaders in ways that promoted a growing sense of Indian identity. Unlike previous foreign rulers, the British never assimilated into Indian society because their acute sense of racial and cultural distinctiveness kept them apart. This served to intensify Indians’ awareness of their collective difference from their alien rulers. Furthermore, British railroads, telegraph lines, postal services, administrative networks, newspapers, and schools as well as the English language bound India’s many regions and peoples together more firmly than ever before and facilitated communication, especially among those with a modern education. Early nineteenth-century cultural nationalists, seeking to renew and reform Hinduism, registered this sense of India as a cultural unit.

The most important political expression of an all-Indian identity took shape in the Indian National Congress (INC), often called the Congress Party, which was established in 1885.This was an association of English-educated Indians—lawyers, journalists, teachers, businessmen—drawn overwhelmingly from regionally prominent high-caste Hindu families. It represented the beginning of a new kind of political protest, quite different from the rebellions, banditry, and refusal to pay taxes that had periodically erupted in the rural areas of colonial India. The INC was largely an urban phenomenon and quite moderate in its demands. Initially, its well-educated members did not seek to overthrow British rule; rather they hoped to gain greater inclusion within the political, military, and business life of British India. From such positions of influence, they argued, they could better protect the interests of India than could their foreign-born rulers. The British mocked their claim to speak for ordinary Indians, referring to them as “babus,” a derogatory term that implied a semi-literate “native” with only a thin veneer of modern culture.

As an elite organization, the INC had difficulty gaining a mass following among India’s vast peasant population. That began to change in the aftermath of World War I. To attract Indian support for the war effort, the British in 1917 had promised “the gradual development of self-governing institutions,” a commitment that energized nationalist politicians to demand more rapid political change. Furthermore, British attacks on the Islamic Ottoman Empire antagonized India’s Muslims. The end of the war was followed by a massive influenza epidemic, which cost the lives of millions of Indians. Finally, a series of violent repressive British actions antagonized many. This was the context in which Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948) arrived on the Indian political scene and soon transformed it.

Change

Question

What was the role of Gandhi in India’s struggle for independence?

[Answer Question]

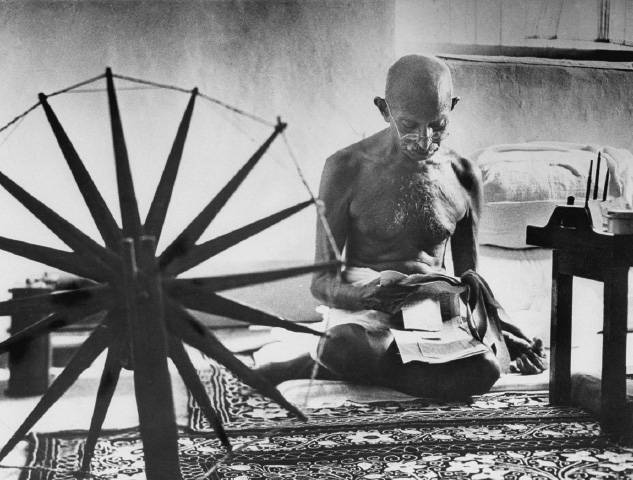

Gandhi was born in the province of Gujarat in western India to a pious Hindu family of the Vaisya, or business, caste. He was married at the age of thirteen, had only a mediocre record as a student, and eagerly embraced an opportunity to study law in England when he was eighteen. He returned as a shy and not very successful lawyer, and in 1893 he accepted a job with an Indian firm in South Africa, where a substantial number of Indians had migrated as indentured laborers during the nineteenth century. While in South Africa, Gandhi personally experienced overt racism for the first time and as a result soon became involved in organizing Indians, mostly Muslims, to protest that country’s policies of racial segregation. He also developed a concept of India that included Hindus and Muslims alike and pioneered strategies of resistance that he would later apply in India itself. His emerging political philosophy, known as satyagraha (truth force), was a confrontational, though nonviolent, approach to political action. As Gandhi argued,

Non-violence means conscious suffering. It does not mean meek submission to the will of the evil-doer, but it means the pitting of one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant. . . . [I]t is possible for a single individual to defy the whole might of an unjust empire to save his honour, his religion, his soul.4

Returning to India in 1915, Gandhi quickly rose within the leadership ranks of the INC. During the 1920s and 1930s, he applied his approach in periodic mass campaigns that drew support from an extraordinarily wide spectrum of Indians—peasants and the urban poor, intellectuals and artisans, capitalists and socialists, Hindus and Muslims. The British responded with periodic repression as well as concessions that allowed a greater Indian role in political life. Gandhi’s conduct and actions—his simple and unpretentious lifestyle, his support of Muslims, his frequent reference to Hindu religious themes—appealed widely in India and transformed the INC into a mass organization. To many ordinary people, Gandhi possessed magical powers and produced miraculous events. He was the Mahatma, the Great Soul.

His was a radicalism of a different kind. He did not call for social revolution but sought the moral transformation of individuals. He worked to raise the status of India’s untouchables, the lowest and most ritually polluting groups within the caste hierarchy, but he launched no attack on caste in general and accepted support from businessmen and their socialist critics alike. His critique of India’s situation went far beyond colonial rule. “India is being ground down,” he argued, “not under the English heel, but under that of modern civilization”—its competitiveness, its materialism, its warlike tendencies, its abandonment of religion.5 Almost alone among nationalist leaders in India or elsewhere, Gandhi opposed a modern industrial future for his country, seeking instead a society of harmonious self-sufficient villages drawing on ancient Indian principles of duty and morality. (See Document 18.4 for a more extended statement of Gandhi’s thinking.)

Gandhi also embraced efforts to mobilize women for the struggle against Britain and to elevate their standing in marriage and society. While asserting the spiritual and mental equality of women and men, he regarded women as uniquely endowed with a capacity for virtue, self-sacrifice, and endurance and thus particularly well suited for nonviolent protest. They could also contribute by spinning and weaving their families’ clothing, while boycotting British textiles. But Gandhi never completely broke with older Indian conceptions of gender roles. “The duty of motherhood . . . ,” he wrote, “requires qualities which man need not possess. She is passive; he is active. She is essentially mistress of the house. He is the bread-winner.”6 Hundreds of thousands of women responded to Gandhi’s call for participation in the independence struggle, marching, demonstrating, boycotting, and spinning. The moral and religious context in which he cast his appeal allowed them to do so without directly challenging traditional gender roles.

Description

Question

What conflicts and differences divided India’s nationalist movement?

[Answer Question]

Gandhi and the INC leadership had to contend with a wide range of movements, parties, and approaches whose very diversity tore at the national unity that they so ardently sought. Whereas Gandhi rejected modern industrialization, his own chief lieutenant, Jawaharlal Nehru, thoroughly embraced science, technology, and industry as essential to India’s future. Nor did everyone accept Gandhi’s nonviolence or his inclusive definition of India. A militant Hindu organization preached hatred of Muslims and viewed India as an essentially Hindu nation. Some in the Congress Party believed that efforts to improve the position of women or untouchables were a distraction from the chief task of gaining independence. Whether to participate in British-sponsored legislative bodies without complete independence also became a divisive issue. Furthermore, a number of smaller parties advocated on behalf of particular regions or castes. India’s nationalist movement, in short, was beset by division and controversy.

By far the most serious threat to a unified movement derived from the growing divide between the country’s Hindu and Muslim populations. As early as 1906, the formation of an All-India Muslim League contradicted the Congress Party’s claim to speak for all Indians. As the British allowed more elected Indian representatives on local councils, the League demanded separate electorates, with a fixed number of seats for Muslims. As a distinct minority within India, some Muslims feared that their voice could be swamped by a numerically dominant Hindu population, despite Gandhi’s inclusive philosophy. Some Hindu politicians confirmed those fears when they cast the nationalist struggle in Hindu religious terms, hailing their country, for example, as a goddess, Bande Mataram (Mother India). When the 1937 elections gave the Congress Party control of many provincial governments, some of those governments began to enforce the teaching of Hindi in schools, rather than Urdu, which is written in a Persian script and favored by Muslims. This policy, as well as Hindu efforts to protect cows from slaughter, antagonized Muslims.

As the movement for independence gained ground, the Muslim League and its leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (JIN-uh), argued that those parts of India that had a Muslim majority should have a separate political status. They called it Pakistan, the land of the pure. In this view, India was not a single nation, as Gandhi had long argued. Jinnah put his case succinctly:

The Muslims and Hindus belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literatures. They neither intermarry nor interdine [eat] together and, indeed, they belong to two different civilizations.7

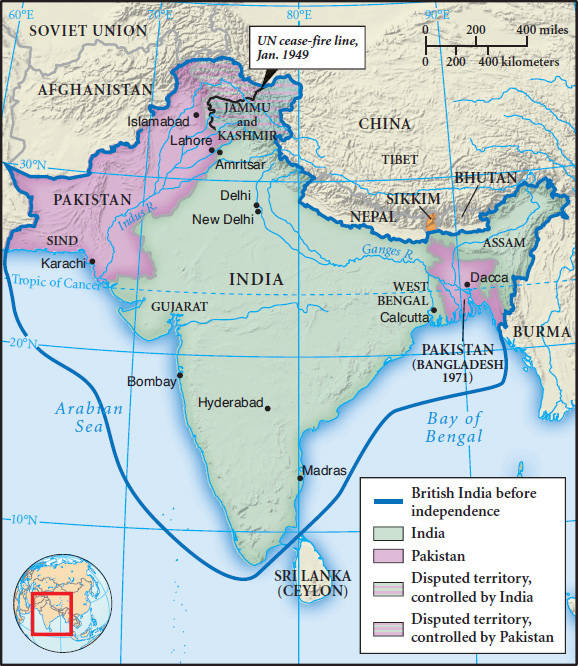

With great reluctance and amid mounting violence, Gandhi and the Congress Party finally agreed to partition as the British declared their intention to leave India after World War II (see Map 22.2).

Thus colonial India became independent in 1947 as two countries—a Muslim Pakistan, itself divided into two wings 1,000 miles apart, and a mostly Hindu India governed by a secular state. Dividing colonial India in this fashion was horrendously painful. A million people or more died in the communal violence that accompanied partition, and some 12 million refugees moved from one country to the other to join their religious compatriots. Gandhi himself, desperately trying to stem the mounting tide of violence in India’s villages, refused to attend the independence celebrations. Only a year after independence, he was assassinated by a Hindu extremist. The great triumph of independence, secured from the powerful British Empire, was overshadowed by the great tragedy of the violence of partition. (See the portrait of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a Muslim pacifist who admired the work of Gandhi.)