Creating Islamic Societies: Resistance and Renewal in the World of Islam

Change

Question

From what sources did Islamic renewal movements derive?

[Answer Question]

The most prominent of the late twentieth-century fundamentalisms was surely that of Islam. Expressed in many and various ways, it was an effort among growing numbers of Muslims to renew and reform the practice of Islam and to create a new religious/political order centered on a particular understanding of their faith. Earlier renewal movements, such as the eighteenth-century Wahhabis (see Expansion and Renewal in the Islamic World), focused largely on the internal problems of Muslim societies, while those of the twentieth century responded as well to the external pressures of colonial rule, Western imperialism, and secular modernity.

Emerging strongly in the last quarter of the century, Islamic renewal movements gained strength from the enormous disappointments that had accumulated in the Muslim world by the 1970s. Conquest and colonial rule; awareness of the huge technological and economic gap between Islamic and European civilizations; the disappearance of the Ottoman Empire, long the chief Islamic state; elite enchantment with Western culture; the retreat of Islam for many to the realm of private life—all of this had sapped the cultural self-confidence of many Muslims by the mid-twentieth century. Political independence for former colonies certainly represented a victory for Islamic societies, but it had given rise to major states—Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia, Iraq, Algeria, and others—that pursued essentially Western and secular policies of nationalism, socialism, and economic development, often with only lip service to an Islamic identity.

Even worse, these policies were not very successful. A number of endemic problems—vastly overcrowded cities with few services, widespread unemployment, pervasive corruption, slow economic growth, a mounting gap between the rich and poor—flew in the face of the great expectations that had accompanied the struggle against European domination. Despite formal independence, foreign intrusion still persisted. Israel, widely regarded as an outpost of the West, had been reestablished as a Jewish state in the very center of the Islamic world in 1948. In 1967, Israel inflicted a devastating defeat on Arab forces in the Six-Day War and seized various Arab territories, including the holy city of Jerusalem. Furthermore, broader signs of Western cultural penetration persisted—secular schools, alcohol, Barbie dolls, European and American movies, scantily clad women. The largely secular leader of independent Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba, argued against the veil for women as well as polygamy for men and discouraged his people from fasting during Ramadan. In 1960 he was shown on television drinking orange juice during the sacred month to the outrage of many traditional Muslims.

This was the context in which the idea of an Islamic alternative to Western models of modernity began to take hold. The intellectual and political foundations of this Islamic renewal had been established earlier in the century. Its leading figures, such as the Indian Mawlana Mawdudi and the Egyptian Sayyid Qutb, insisted that the Quran and the sharia (Islamic law) provided a guide for all of life—political, economic, and spiritual—and a blueprint for a distinctly Islamic modernity not dependent on Western ideas. It was the departure from Islamic principles, they argued, that had led the Islamic world into decline and subordination to the West, and only a return to the “straight path of Islam” would ensure a revival of Muslim societies. That effort to return to Islamic principles was labeled jihad, an ancient and evocative religious term that refers to “struggle” or “striving” to please God. In its twentieth-century political expression, jihad included the defense of an authentic Islam against Western aggression and vigorous efforts to achieve the Islamization of social and political life within Muslim countries. It was a posture that would enable Muslims to resist the seductive but poisonous culture of the West. Sayyid Qutb had witnessed that culture during a visit to the United States in the late 1940s and was appalled by what he saw:

Look at this capitalism with its monopolies, its usury . . . at this individual freedom, devoid of human sympathy and responsibility for relatives except under force of law; at this materialistic attitude which deadens the spirit; at this behavior like animals which you call “free mixing of the sexes”; at this vulgarity which you call “emancipation of women”; at this evil and fanatical racial discrimination.19

The earliest mass movement to espouse such ideas was Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928 by an impoverished schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna (1906–1949). Advocating “government that will act in conformity to the law and Islamic principles,” the Brotherhood soon attracted a substantial following, including many poor urban residents recently arrived from the countryside. Still a major presence in Egyptian political life, the Brotherhood has frequently come into conflict with state authorities.

Comparison

Question

In what different ways did Islamic renewal express itself?

[Answer Question]

By the 1970s, such ideas and organizations echoed widely across the Islamic world and found expression in many ways. At the level of personal life, many people became more religiously observant, attending mosque, praying regularly, and fasting. Substantial numbers of women, many of them young, urban, and well educated, adopted modest Islamic dress and the veil quite voluntarily. Participation in Sufi mystical practices increased in some places. Furthermore, many governments sought to anchor themselves in Islamic rhetoric and practice. During the 1970s, President Anwar Sadat of Egypt claimed the title of “Believer-President,” referred frequently to the Quran, and proudly displayed his “prayer mark,” a callus on his forehead caused by touching his head to the ground in prayer. Under pressure from Islamic activists, the government of Sudan in the 1980s adopted Quranic punishments for various crimes (such as amputating the hand of a thief ) and announced a total ban on alcohol, dramatically dumping thousands of bottles of beer and wine into the Nile.

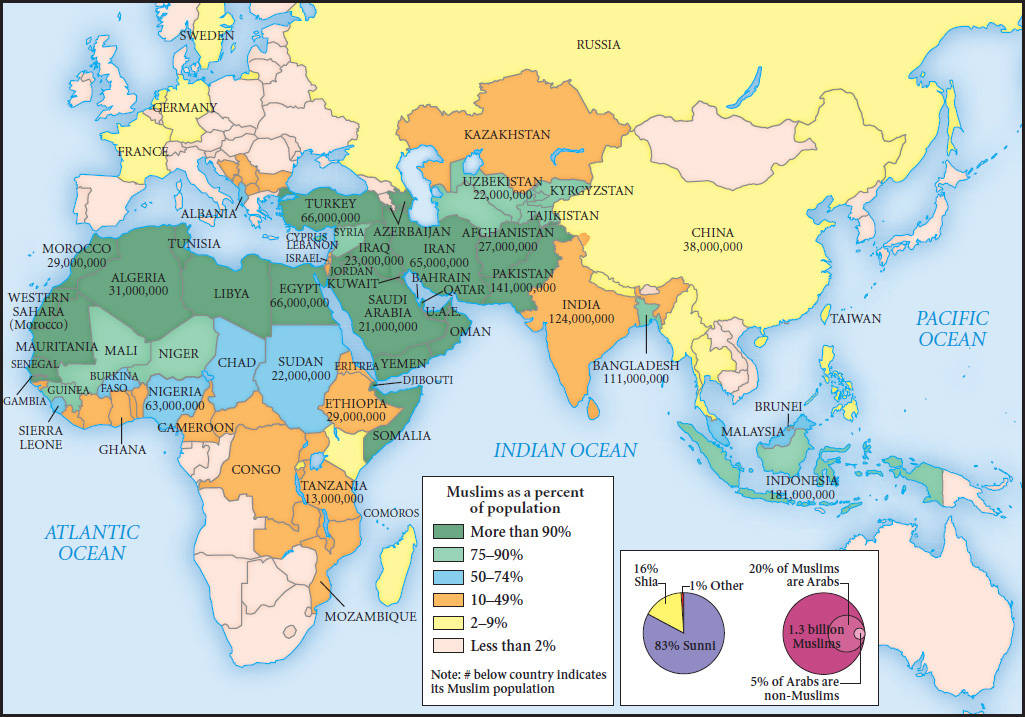

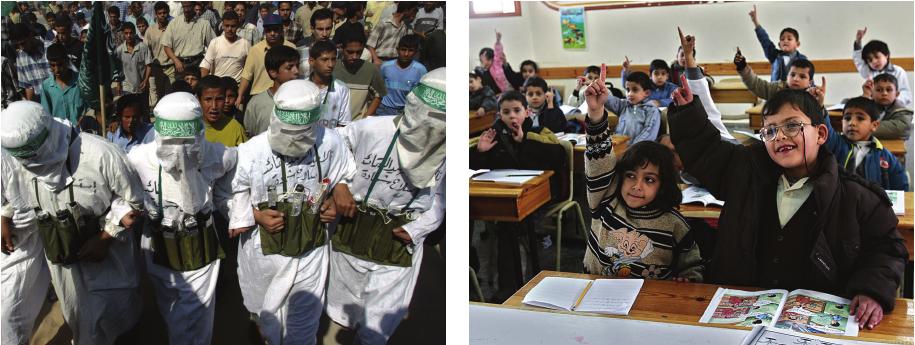

All over the Muslim world, from North Africa to Indonesia (see Map 23.3), Islamic renewal movements spawned organizations that operated legally to provide social services—schools, clinics, youth centers, legal-aid societies, financial institutions, publishing houses—that the state offered inadequately or not at all. Islamic activists took leadership roles in unions and professional organizations of teachers, journalists, engineers, doctors, and lawyers. Such people embraced modern science and technology but sought to embed these elements of modernity within a distinctly Islamic culture. Some served in official government positions or entered political life and contested elections where it was possible to do so. The Algerian Islamic Salvation Front was poised to win elections in 1992, when a frightened military government intervened to cancel the elections, an action that plunged the country into a decade of bitter civil war.

Another face of religious renewal, however, sought the overthrow of what they saw as compromised regimes in the Islamic world, most successfully in Iran in 1979 , but also in Afghanistan (1996) and parts of northern Nigeria (2000). Here Islamic movements succeeded in coming to power and began to implement a program of Islamization based on the sharia. Elsewhere military governments in Pakistan and Sudan likewise introduced elements of sharia-based law. Hoping to spark an Islamic revolution, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad organization assassinated President Sadat in 1981, following Sadat’s brutal crackdown on both Islamic and secular opposition groups. One of the leaders of Islamic Jihad explained:

We have to establish the Rule of God’s Religion in our own country first, and to make the Word of God supreme. . . . There is no doubt that the first battlefield for jihad is the extermination of these infidel leaders and to replace them by a complete Islamic Order.20

Islamic revolutionaries also took aim at hostile foreign powers. Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon, supported by the Islamic regime in Iran, targeted Israel with popular uprisings, suicide bombings, and rocket attacks in response to the Israeli occupation of Arab lands. For some, Israel’s very existence was illegitimate. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 prompted widespread opposition aimed at liberating that country from atheistic communism and creating an Islamic state. Sympathetic Arabs from the Middle East flocked to the aid of their Afghan compatriots.

Among them was the young Osama bin Laden, a wealthy Saudi Arab, who created an organization, al-Qaeda (meaning “the base” in Arabic), to funnel fighters and funds to the Afghan resistance. At the time, bin Laden and the Americans were on the same side, both opposing Soviet expansion into Afghanistan, but they soon parted ways. Returning to his home in Saudi Arabia, bin Laden became disillusioned and radicalized when the government of his country allowed the stationing of “infidel” U.S. troops in Islam’s holy land during and after the first American war against Iraq in 1991. By the mid-1990s, he had found a safe haven in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, from which he and other leaders of al-Qaeda planned their attack on the World Trade Center and other targets in the United States on September 11, 2001. Although they had no standing as Muslim clerics, in 1998 they had issued a fatwa (religious edict) declaring war on America:

[F]or over seven years the United States has been occupying the lands of Islam in the holiest of places, the Arabian Peninsula, plundering its riches, dictating to its rulers, humiliating its people, terrorizing its neighbors, and turning its bases in the Peninsula into a spearhead through which to fight the neighboring Muslim peoples. . . . [T]he ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and the holy mosque (in Mecca) from their grip, and in order for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim.21

Elsewhere as well—in East Africa, Indonesia, Great Britain, Spain, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen—al-Qaeda or groups associated with it launched scattered attacks on Western interests. At the international level, the great enemy was not Christianity itself or even Western civilization, but irreligious Western-style modernity, U.S. imperialism, and an American-led economic globalization so aptly symbolized by the World Trade Center. Ironically, al-Qaeda itself was a modern and global organization, many of whose members were highly educated professionals from a variety of countries.

Despite this focus on the West, the violent struggles undertaken by politicized Islamic activists were as much within the Islamic world as they were with the external enemy. Their understanding of Islam, heavily influenced by Wahhabi ideas, was in various ways quite novel and at odds with classical Islamic practice. It was highly literal and dogmatic in its understanding of the Quran, legalistic in its effort to regulate the minute details of daily life, deeply opposed to any “innovation” in religious practice, inclined to define those who disagreed with them as “non-Muslims,” and drawn to violent jihad as a legitimate part of Islamic life. It was also deeply skeptical about the interior spiritual emphasis of Sufism, which had informed so much of earlier Islamic culture. The spread of this version of Islam, often known as Salafism, owed much to massive financial backing from oil-rich Saudi Arabia, which funded Wahhabi/Salafi mosques and schools across the Islamic world and in the West as well.