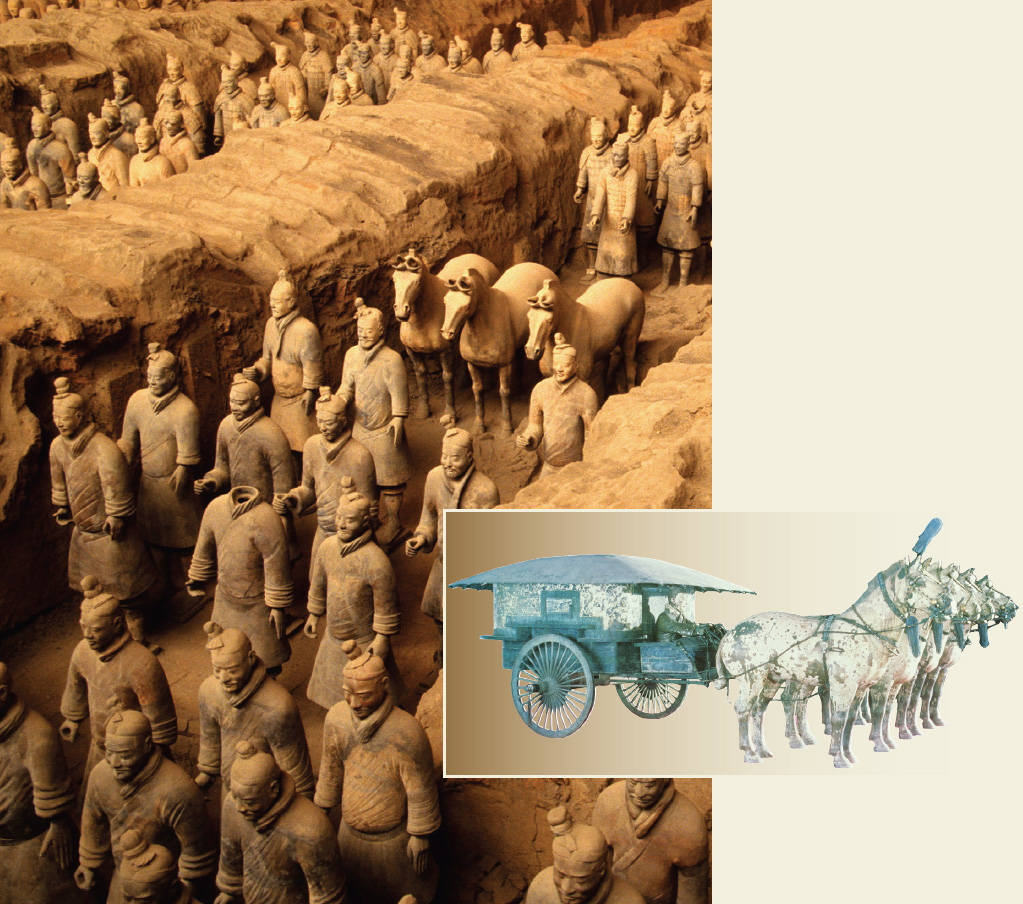

Visual Source 3.3

Qin Shihuangdi Funerary Complex

Surely the most stunning representation of political power during the second-wave era derived from China and expressed the grand conception of empire associated with Qin Shihuangdi, the so-called First Emperor (r. 221–210 B.C.E.). In his view, the empire he created was to be universal, even cosmic, in scope. In tours throughout his vast realm, he offered sacrifices to the various spirits, bringing them, as well as the rival kingdoms of China, into a state of unity and harmony. One of the inscriptions he left behind suggested the scale of his reign: “He universally promulgated the shining laws, gave warp and woof to all under heaven.”19 Qin Shihuangdi saw himself in the line of ancient sage kings, who had originally given order to the world. But the empire was also to be an eternal realm. The emperor vigorously pursued personal immortality, seeking out pills, herbs, and potions believed to convey eternal life and sending expeditions to the mythical Isles of the Immortals, thought to lie off the east coast of China. All of this found expression in the vast funerary complex constructed for Qin Shihuangdi during his lifetime near the modern city of Xian.

In early 1974, some Chinese peasants digging a well stumbled across a small corner of that complex, leading to what has become perhaps the most celebrated archeological discovery of the twentieth century. In subsequent and continuing excavations, archeologists have uncovered thousands of life-size ceramic statues of soldiers of various ranks, arrayed for battle and equipped with real weapons. Other statues portrayed officials, acrobats, musicians, wrestlers, horses, bronze chariots, birds, and more—all designed to accompany Qin Shihuangdi into the afterlife.

This amazing discovery, however, was only a very small part of an immense tomb complex covering some fifty-six square kilometers and centered on the still-unexcavated burial mound of Qin Shihuangdi. Begun in 246 B.C.E. and still incomplete when Shihuangdi died in 210 B.C.E., the construction of this gigantic complex was described by the great Chinese historian Sima Qian about a century later:

As soon as the First Emperor became king of Qin, excavations and building had been started at Mount Li, while after he won the empire, more than 700,000 conscripts from all parts of the country worked there. They dug through three subterranean streams and poured molten copper for the outer coffin, and the tomb was filled with . . . palaces, pavilions, and offices as well as fine vessels, precious stones, and rarities. Artisans were ordered to fix up crossbows so that any thief breaking in would be shot. All the country’s streams, the Yellow River and the Yangtze were reproduced in quicksilver [mercury] and by some mechanical means made to flow into a miniature ocean. The heavenly constellations were above and the regions of the earth below. The candles were made of whale oil to insure the burning for the longest possible time.20

Buried with the First Emperor were many of the workers who had died or were killed during construction as well as sacrificed aristocrats and concubines.

This massive project was no mere monument to a deceased ruler. In a culture that believed the living and the dead formed a single community, Qin Shihuangdi’s tomb complex was a parallel society, complete with walls, palaces, cemeteries, demons, spirits, soldiers, administrators, entertainers, calendars, texts, divination records, and the luxurious objects appropriate to royalty. The tomb mound itself was like a mountain, a geographic feature that in Chinese thinking was home to gods, spirits, and immortals. From this mound, Qin Shihuangdi would rule forever over his vast domain, although invisible to the living.

Visual Source 3.3 displays a part of the terra cotta army, containing some 6,000 figures, which guarded the entryway to Qin Shihuangdi’s tomb, while the chapter opening picture shows a kneeling archer, who was a part of this army. The insert image shows an exquisitely detailed bronze carriage, pulled by four horses, found some distance away, quite close to the actual burial place of the emperor. The compartment is decorated inside and out with geometric and cloud patterns, while the round roof, perhaps, represents the sun, the sky, or the heavens above. Perhaps it was intended to allow the emperor to tour his realm in the afterlife much as he had done while alive. Or did it serve a one-time purpose to transport the emperor’s soul into the afterlife?

Question

How do you suppose Qin Shihuangdi thought about the function of this “army” and the carriage in the larger context of his tomb complex? What might it add to his ability to exercise power and project authority?

Question

How does the fact that this funerary complex was largely invisible to the general public affect your understanding of its function? How might ordinary Chinese have viewed the construction of this complex even before it was completed?

Question

To what extent is the conception of political authority reflected in this funerary complex in keeping with the ideas of Han Fei in Document 3.3? How might it challenge those ideas?

Question

How do you understand the religious or cosmic dimension of Chinese political thinking as reflected in this tomb complex?