The Spread of New Religions

Change

Question

In what ways was Christianity transformed in the five centuries following the death of Jesus?

[Answer Question]

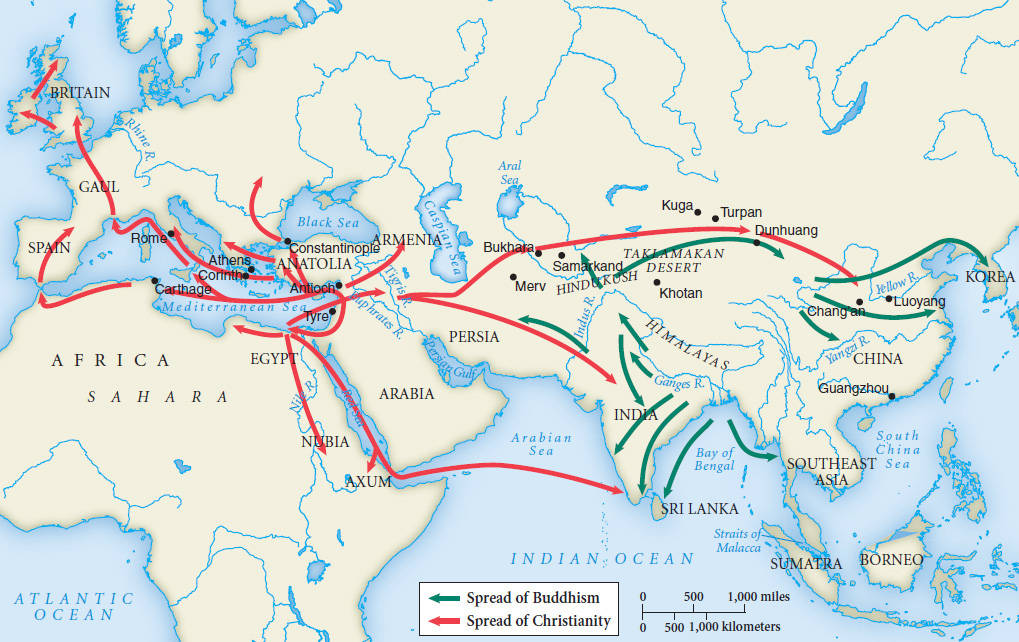

Neither Jesus nor the Buddha had any intention of founding a new religion; rather, they sought to revitalize the traditions from which they had come. Nonetheless, Christianity and Buddhism soon emerged as separate religions, distinct from Judaism and Hinduism, proclaiming their messages to a much wider and more inclusive audience. In the process, both teachers were transformed by their followers into gods. According to many scholars, Jesus never claimed divine status, seeing himself as a teacher or a prophet, whose close relationship to God could be replicated by anyone.18 The Buddha likewise viewed himself as an enlightened but fully human person, an example of what was possible for all who followed the path. But in Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddha became a supernatural being who could be worshipped and prayed to and was spiritually available to his followers. Jesus also soon became divine in the eyes of his early followers, such as Saint Paul and Saint John. According to one of the first creeds of the Church, he was “the Son of God, Very God of Very God,” while his death and resurrection made possible the forgiveness of sins and the eternal salvation of those who believed.

The transformation of Christianity from a small Jewish sect to a world religion began with Saint Paul (10–65 C.E.), an early convert whose missionary journeys in the eastern Roman Empire led to the founding of small Christian communities that included non-Jews. The Good News of Jesus, Paul argued, was for everyone, and Gentile (non-Jewish) converts need not follow Jewish laws or rituals such as circumcision. In one of his many letters to these new communities, later collected as part of the New Testament, Paul wrote, “There is neither Jew nor Greek . . . neither slave nor free . . . neither male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”19

Despite Paul’s egalitarian pronouncement, early Christianity, like Buddhism, offered a mix of opportunities and restrictions for women. Jesus himself had interacted easily with a wide range of women, and they had figured prominently among his followers. Some scholars have argued that Mary Magdalene was a part of his inner circle.20 And women played leadership roles in the “house churches” of the first century C.E. Nonetheless, Paul counseled women to “be subject to your husbands” and declared that “it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.” Men were identified with the role of Christ himself when Paul argued that “the husband is head of the wife as Christ is head of the Church.”21 It was not long before male spokesmen for the faith had fully assimilated older and highly negative views of women. As daughters of Eve, they were responsible for the introduction of sin and evil into the world and were the source of temptation for men. On the other hand, Jesus’ mother Mary soon became the focus of a devotional cult; women were among the martyrs of the early church; and growing numbers of Christian women, like their Buddhist counterparts, found a more independent space in the monasteries, even as the official hierarchy of the Church became wholly male.

Nonetheless, the inclusive message of early Christianity was one of the attractions of the new faith as it spread very gradually within the Roman Empire during the several centuries after Jesus’ death. The earliest converts were usually lower-stratum people—artisans, traders, and a considerable number of women—mostly from towns and cities, while a scattering of wealthier, more prominent, and better-educated people subsequently joined the ranks of Christians.22 The spread of the faith was often accompanied by reports of miracles, healings, and the casting out of demons—all of which were impressive to people thoroughly accustomed to seeing the supernatural behind the events of ordinary life. Christian communities also attracted converts by the way their members cared for one another. In the middle of the third century C.E., the Church in Rome supported 154 priests (of whom 52 were exorcists) and some 1,500 widows, orphans, and destitute people.23 By 300 C.E., perhaps 10 percent of the Roman Empire’s population (some 5 million people) identified themselves as Christians.

Although Christians in the West often think of their faith as a European-centered religion, during the first six centuries of the Christian era, most followers of Jesus lived in the non-European regions of the Roman Empire—North Africa, Egypt, Anatolia, Syria—or outside of the empire altogether in Arabia, Persia, Ethiopia, India, and China. Saint Paul’s missionary journeys had established various Christian communities in the Roman province of Asia—what is now Turkey—and also in Syria, where the earliest recorded Christian church building was located. The Syrian church also developed a unique liturgy with strong Jewish influences and a distinctive musical tradition of chants and hymns. The language of that liturgy was neither Greek nor Latin, but Syriac, a Semitic tongue closely related to Aramaic, which Jesus spoke.

From Syria, the faith spread eastward into Persia, where it attracted a substantial number of converts, many of them well educated in the sciences and medicine, by the third century C.E. Those converts also encountered periodic persecution from the Zoroastrian rulers of Persia and were sometimes suspected of political loyalty to the Roman Empire, Persia’s longtime enemy and rival. To the north of Syria on the slopes of the Caucasus Mountains, the Kingdom of Armenia became the first place where rulers adopted Christianity as a state religion. In time, Christianity became—and remains to this day—a central element of Armenian national identity. A distinctive feature of Armenian Christianity involved the ritual killing of animals at the end of the worship service, probably a continuation of earlier pre-Christian practices.

Syria and Persia represented the core region of the Church of the East, distinct both theologically and organizationally from the Latin church focused on Rome and an emerging Eastern Orthodox church based in Constantinople. Its missionaries took Christianity even farther to the east. By the fourth century, and perhaps much earlier, a well-organized church had taken root in southern India, which later gained tax privileges and special rights from local rulers. In the early seventh century a Persian monk named Alopen initiated a small but remarkable Christian experiment in China, described more fully in Chapter 10. A modest Christian presence in Central Asia was also an outgrowth of this Church of the East.

In other directions as well, Christianity spread from its Palestinian place of origin. By the time Muhammad was born in 570, a number of Arabs had become Christians. One of them, in fact, was among the first to affirm Muhammad as an authentic prophet. A particularly vibrant center of Christianity developed in Egypt, where tradition holds that Jesus’s family fled to escape persecution of King Herod. Egyptian priests soon translated the Bible into the Egyptian language known as Coptic, and Egyptian Christians pioneered various forms of monasticism. By 400 C.E., hundreds of monasteries, cells, and caves dotted the desert, inhabited by reclusive monks dedicated to their spiritual practices. Increasingly, the language, theology, and practice of Egyptian Christianity diverged from that of Rome and Constantinople, giving expression to Egyptian resistance against Roman or Byzantine oppression.

To the west of Egypt, a Church of North Africa furnished a number of the intellectuals of the early Church including Saint Augustine as well as many Christian martyrs to Roman persecution (see Portrait of Perpetua on the next page). Here and elsewhere the coming of Christianity not only provoked hostility from Roman political authorities but also tensions within families. The North African Carthaginian writer Tertullian (160–220 C.E.), known as the “father of Latin Christianity,” described the kind of difficulties that might arise between a Christian wife and her “pagan” husband:

She is engaged in a fast; her husband has arranged a banquet. It is her Christian duty to visit the streets and the homes of the poor; her husband insists on family business. She celebrates the Easter Vigil throughout the night; her husband expects her in his bed. . . . She who has taken a cup at Eucharist will be required to take of a cup with her husband in the tavern. She who has foresworn idolatry must inhale the smoke arising from the incense on the altars of the idols in her husband’s home.24

Further south in Africa, Christianity became during the fourth century the state religion of Axum, an emerging kingdom in what is now Eritrea and Ethiopia (see Chapter 6). This occurred at about the same time as both Armenia and the Roman Empire officially endorsed Christianity. In Axum, a distinctively African expression of Christianity took root with open-air services, the use of drums and stringed instruments in worship, and colorful umbrellas covering priests and musicians from the elements. Linked theologically and organizationally to Coptic Christianity in Egypt, the Ethiopian church used Ge’ez, a local Semitic language and script, for its liturgy and literature.

In the Roman world, the strangest and most offensive feature of the new faith was its exclusive monotheism and its antagonism to all other supernatural powers, particularly the cult of the emperors. Christians’ denial of these other gods caused them to be tagged as “atheists” and was one reason behind the empire’s intermittent persecution of Christians during the first three centuries of the Common Era. All of that ended with Emperor Constantine’s conversion in the early fourth century C.E. and with growing levels of state support for the new religion in the decades that followed.

Roman rulers sought to use an increasingly popular Christianity as glue to hold together a very diverse population in a weakening imperial state. Constantine and his successors thus provided Christians with newfound security and opportunities. The emperor Theodosius (r. 379–395 C.E.) enforced a ban on all polytheistic ritual sacrifices and ordered their temples closed. Christians by contrast received patronage for their buildings, official approval for their doctrines, suppression of their rivals, prestige from imperial recognition, and, during the late fourth century, the proclamation of Christianity as the official state religion. All of this set in motion a process by which the Roman Empire, and later all of Europe, became overwhelmingly Christian. At the time, however, Christianity was expanding at least as rapidly to the east and south as it was to the west. In 500, few observers could have predicted that the future of Christianity would lie primarily in Europe rather than in Asia and Africa.

The spread of Buddhism in India was quite different from that of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Even though Ashoka’s support gave Buddhism a considerable boost, it was never promoted to the exclusion of other faiths. Ashoka sought harmony among India’s diverse population through religious tolerance rather than uniformity. The kind of monotheistic intolerance that Christianity exhibited in the Roman world was quite foreign to Indian patterns of religious practice. Although Buddhism subsequently died out in India as it was absorbed into a reviving Hinduism, no renewal of Roman polytheism occurred, and Christianity became an enduring element of European civilization. Nonetheless, Christianity did adopt some elements of religious practice from the Roman world, including perhaps the cult of saints and the dating of the birth of Jesus to the winter solstice. In both cases, however, these new religions spread widely beyond their places of origin. Buddhism provided a network of cultural connections across much of Asia, while Christianity during its early centuries established an Afro-Eurasian presence.