PORTRAIT Piye, Kushite Conqueror of Egypt

During the eighth century B.C.E., a remarkable reversal took place in northeastern Africa. The ancient Kingdom of Kush in the southern Nile Valley, long under the control of Egypt, conquered its former ruler and governed it for a century. The primary agent of that turnabout was Piye, a Kushite ruler (r. 752–721 B.C.E.), who recorded his great victory in a magnificent inscription that provides some hints about his own personality and outlook on the world.3

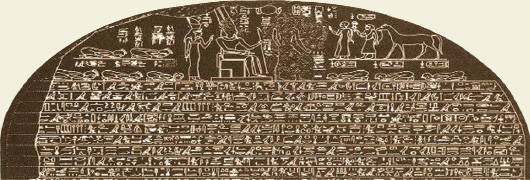

The very beginning of the inscription discloses Piye’s self-image, for he declares himself a “divine emanation, living image of Atum,” the Egyptian creator-god closely connected to kingship. Like most of the Kushite elite, Piye had thoroughly assimilated much of Egyptian culture and religion, becoming perhaps “more Egyptian than the Egyptians.”4 Even the inscription was written in hieroglyphic Egyptian and in the style of earlier pharaohs. Who better then to revive an Egypt that, over the past several centuries, had become hopelessly fragmented and that also had neglected the worship of Amun? Thus Piye’s conquest reflected the territorial ambitions of Kush’s “Egyptianized” rulers, a sense of divinely inspired mission to set things right in Egypt, and the opportunity presented by the sorry state of Egyptian politics.

If we are to believe the inscription, Piye went to war reluctantly and only in response to requests from various Egyptian “princes, counts, and generals.” Furthermore he was careful to pay respect to the gods all along the way. After celebrating the new year in 730 B.C.E., Piye departed from his capital of Napata and made an initial stop in Thebes, a southern Egyptian city already controlled by Kushite forces. There he took part in the annual Opet Festival, honoring Amun, his wife Mut (Egypt’s mother goddess), and their offspring Khonsu, associated with the moon. Moving north, Piye then laid siege to Hermopolis, located in middle Egypt. From a high tower, archers poured arrows into the city and “slingers” hurled stones, “slaying people among them daily,” according to the inscription. Soon the city had become “foul to the nose,” and its ruler, Prince Namlot, prepared for surrender. He sent his wife and daughter, lying on their bellies, to plead with the women in Piye’s entourage, begging them to intercede with Piye, which they did. Grandly entering the city, Piye went first to the temple of the chief god, where he offered sacrifices of “bulls, calves and fowl.” To establish his authority, he then “entered every chamber of [Namlot’s] house, his treasury and his magazines.” Piye pointedly ignored the women of Namlot’s harem when they greeted him “in the manner of women.” Yet in the stable, he was moved by the suffering of the horses. He seized Namlot’s possessions for his treasury and assigned his enemy’s grain to the temple of Amun.

And so it went as Piye moved northward. Many cities capitulated without resistance, offering their treasure to the Kushites. Presenting himself as a just and generous conqueror, Piye declared that “not a single one has been slain therein, except the enemies who blasphemed against the god, who were dispatched as rebels.” However, it was a different story when he arrived outside of the major north Egyptian city of Memphis, then ruled by the Libyan chieftain Tefnakht. There “a multitude of people were slain” before Tefnakht was induced to surrender, sending an envoy to Piye to deliver an abject and humiliating speech: “Be thou appeased! I have not beheld thy face for shame; I cannot stand before thy flame, I tremble at thy might.” The city was ritually cleansed; proper respect was paid to the gods, who confirmed Piye’s kingship; and tribute was collected. Soon all resistance collapsed, and Piye, once ruler of a small Kushite kingdom, found himself master of all Egypt.

And then, surprisingly, he departed, leaving his underlings in charge and his sister as the High Priestess and wife of Amun in Thebes. His ships “were laden with silver, gold, copper, clothing, and everything of the Northland, every product of Syria, and all sweet woods of God’s Land [Egypt]. His majesty sailed up-stream, with glad heart.” Never again did Piye set foot in Egypt, preferring to live out his days in his native country, where he was buried in an Egyptian-style pyramid. But he had laid the foundation for a century of Kushite rule in Egypt, reunifying that ancient country, reinvigorating the cult of Amun, and giving expression to the vitality of an important African civilization.

Question

Questions: How did Piye understand himself and his actions in Egypt? How might modern historians view his conquests?