Visual Source 7.5

Islam, Shamanism, and the Turks

Among the Central Asian peoples of Silk Roads, none had a longer-lasting impact on world history than the Turks, a term that refers to a variety of groups speaking related Turkic languages. Originating as pastoral nomads in what is now Mongolia, Turkic peoples gradually migrated westward, occupying much of Central Asia, sometimes creating sizeable empires and settling down as farmers. But the greatest transformation of Turkic culture was a product of conversion to Islam. That process took place between the tenth and fourteenth centuries, as Muslim armies penetrated Central Asia and Muslim merchants became prominent traders on the Silk Roads.

Also very important in the Turks’ conversion to Islam were Muslim holy men known as dervishes. Operating within the Sufi tradition of Islam, dervishes were spiritual seekers who sought a direct personal experience of the Divine Reality and developed reputations for good works, personal kindness, and sometimes magical or religious powers. A Turkic tale from the fourteenth century tells the story of one such holy man, Baba Tukles, sent by God to convert a ruler named Ozbek Khan. To overcome the opposition of the khan’s traditional shamans, Baba Tukles invited one of the shamans to enter a fiery-hot oven pit with him. The shaman was instantly incinerated, while the Muslim holy man emerged unscathed from that test of religious power.38 Such tales of the supernatural and the conversion of rulers contributed to the attractiveness of Islam among Turkic peoples and have been a common feature in the spread of all of the major world religions.

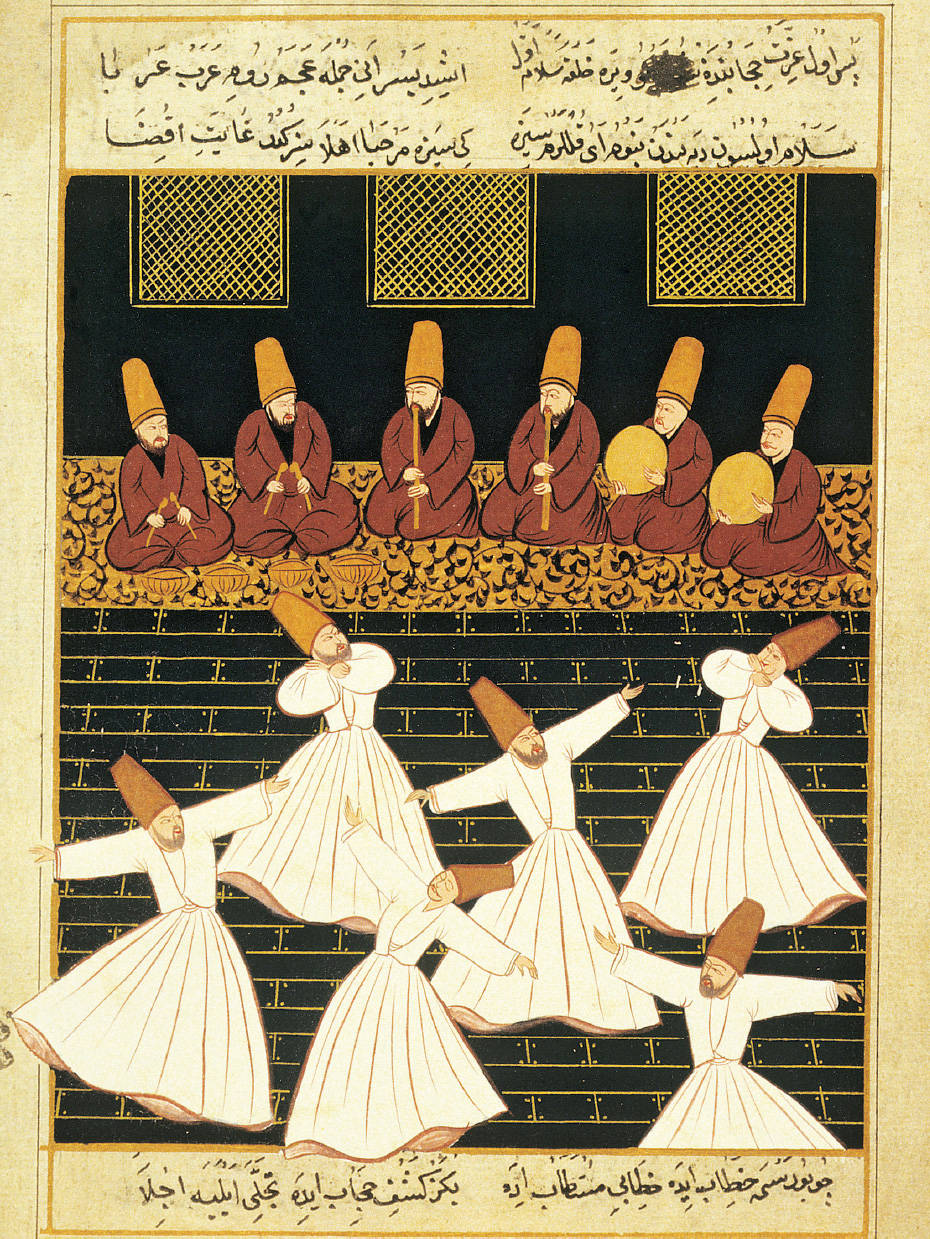

Visual Source 7.5, a painting dating from the sixteenth century, shows a number of Turkish dervishes performing the turning or whirling dance associated with the Sufi religious order established in the thirteenth century by the great mystical poet Rumi.

Intended to bring participants into direct contact with the Divine, the whirling dance itself drew on the ideas and practices of ancient Central Asian religious life in which practitioners, known as shamans, entered into an ecstatic state of consciousness and connection to the spirit world. “Especially in Central Asia, the Caucasus and Anatolia,” writes one scholar, “the mystical ecstasy [of the whirling dance] was understood in the spirit of the shamanic tradition.”39 This blending of two religious traditions—mystical or Sufi Islam and shamanism—represents yet another example of the cultural interactions that washed across the Silk Roads during the third-wave millennium.

Question

What image of these dervishes was the artist trying to convey?

Question

Why might such holy men have been effective carriers of Islam in Central Asia?

Question

Notice the musical instruments that accompany the turning dance—sticks on the left, a flutelike instrument known as a ney in the center, and drums on the right. What do you think this music and dance contributed to the religious experience of the participants?