Women in the Song Dynasty

Change

Question

In what ways did women’s lives change during the Tang and Song dynasties?

[Answer Question]

The “golden age” of Song dynasty China was perhaps less than “golden” for many of its women, for that era marked yet another turning point in the history of Chinese patriarchy. Under the influence of steppe nomads, whose women led less restricted lives, elite Chinese women of the Tang dynasty era, at least in the north, had participated in social life with greater freedom than in earlier times. Paintings and statues show aristocratic women riding horses, while the Queen Mother of the West, a Daoist deity, was widely worshipped by female Daoist priests and practitioners (see Visual Sources 8.2 and 8.4). By the Song dynasty, however, a reviving Confucianism and rapid economic growth seemed to tighten patriarchal restrictions on women and to restore some of the earlier Han dynasty notions of female submission and passivity.

Once again Confucian writers highlighted the subordination of women to men and the need to keep males and females separate in every domain of life. The Song dynasty historian and scholar Sima Guang (1019–1086) summed up the prevailing view: “The boy leads the girl, the girl follows the boy; the duty of husbands to be resolute and wives to be docile begins with this.”11 For men, masculinity came to be defined less in terms of horseback riding, athleticism, and the warrior values of northern nomads and more in terms of the refined pursuits of calligraphy, scholarship, painting, and poetry. Corresponding views of feminine qualities emphasized women’s weakness, reticence, and delicacy. Women were also frequently viewed as a distraction to men’s pursuit of a contemplative and introspective life. The remarriage of widows, though legally permissible, was increasingly condemned, for “to walk through two courtyards is a source of shame for a woman.”12

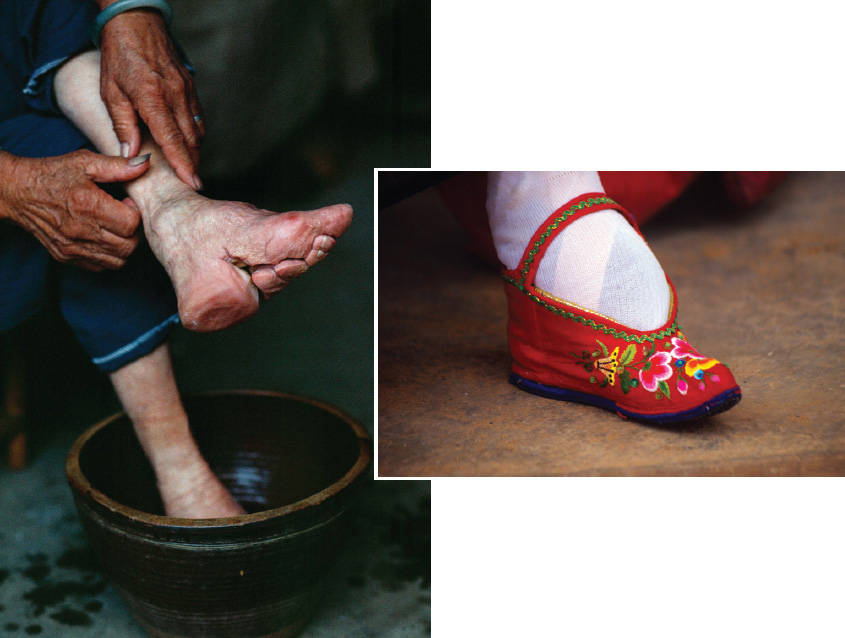

The most compelling expression of a tightening patriarchy lay in foot binding. Apparently beginning among dancers and courtesans in the tenth or eleventh century C.E., this practice involved the tight wrapping of young girls’ feet, usually breaking the bones of the foot and causing intense pain. During and after the Song dynasty, foot binding spread widely among elite families and later became even more widespread in Chinese society. It was associated with new images of female beauty and eroticism that emphasized small size, frailty, and deference and served to keep women restricted to the “inner quarters,” where Confucian tradition asserted that they belonged. Many mothers imposed this painful procedure on their daughters, perhaps to enhance their marriage prospects and to assist them in competing with concubines for the attention of their husbands.13 For many women it became a rite of passage and source of some pride in their tiny feet and the beautiful slippers that encased them, even the occasion for poetry for some literate women. Foot binding also served to distinguish Chinese women from their “barbarian” counterparts and elite women from commoners and peasants.

Furthermore, a rapidly commercializing economy undermined the position of women in the textile industry. Urban workshops and state factories, run by men, increasingly took over the skilled tasks of weaving textiles, especially silk, which had previously been the work of rural women in their homes. Although these women continued to tend silk worms and spin silk thread, they had lost the more lucrative income-generating work of weaving silk fabrics. But as their economic role in textile production declined, other opportunities beckoned in an increasingly prosperous Song China. In the cities, women operated restaurants, sold fish and vegetables, and worked as maids, cooks, and dressmakers. The growing prosperity of elite families funneled increasing numbers of women into roles as concubines, entertainers, courtesans, and prostitutes. Their ready availability surely reduced the ability of wives to negotiate as equals with their husbands, setting women against one another and creating endless household jealousies.

In other ways, the Song dynasty witnessed more positive trends in the lives of women. Their property rights expanded, in terms of controlling their own dowries and inheriting property from their families. “Neither in earlier nor in later periods,” writes one scholar, “did as much property pass through women’s hands” as during the Song dynasty.14 Furthermore, lower-ranking but ambitious officials strongly urged the education of women, so that they might more effectively raise their sons and increase the family’s fortune. Song dynasty China, in short, offered a mixture of tightening restrictions and new opportunities to its women.