War, Conquest, and Tolerance

Change

Question

Why were Arabs able to construct such a huge empire so quickly?

[Answer Question]

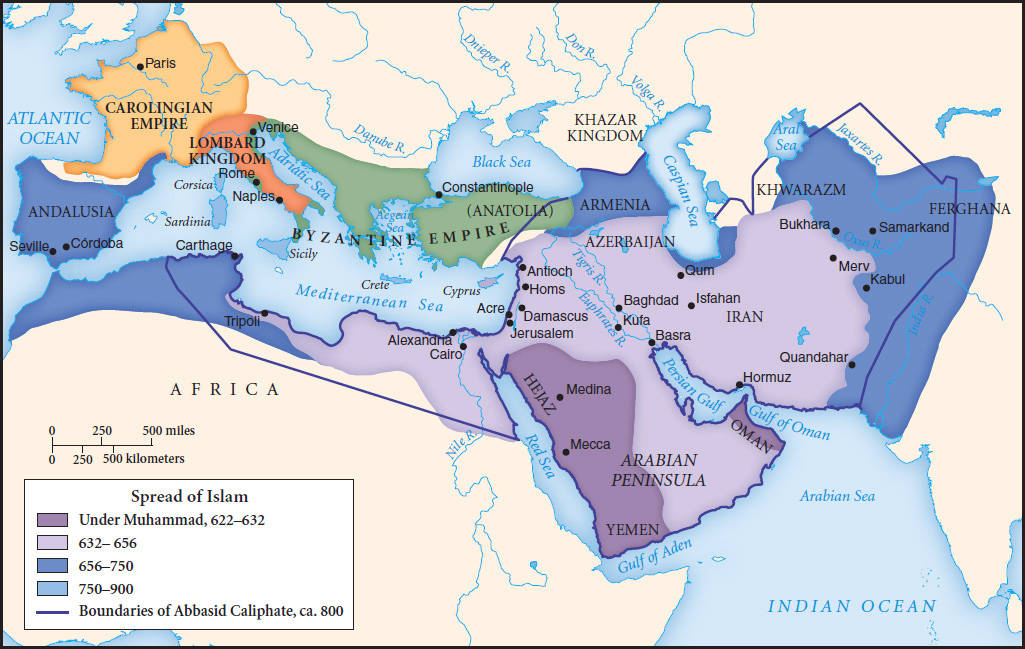

Within a few years of Muhammad’s death in 632, Arab armies engaged the Byzantine and Persian Sassanid empires, the great powers of the region. It was the beginning of a process that rapidly gave rise to an Arab empire that stretched from Spain to India, penetrating both Europe and China and governing most of the lands between them (see Map 9.2). In creating that empire, Arabs were continuing a long pattern of tribal raids into surrounding civilizations, but now these Arabs were newly organized in a state of their own with a central command able to mobilize the military potential of the entire population. The Byzantine and Persian empires, weakened by decades of war with each other and by internal revolts, continued to view the Arabs as a mere nuisance rather than a serious threat. But by 644 the Sassanid Empire had been defeated by Arab forces, while Byzantium, the remaining eastern regions of the old Roman Empire, soon lost the southern half of its territories. Beyond these victories, Muslim forces, operating on both land and sea, swept westward across North Africa, conquered Spain in the early 700s, and attacked southern France. To the east, Arab armies reached the Indus River and seized some of the major oases towns of Central Asia. In 751, they inflicted a crushing defeat on Chinese forces in the Battle of Talas River, which had lasting consequences for the cultural evolution of Asia, for it checked the further expansion of China to the west and made possible the conversion to Islam of Central Asia’s Turkic-speaking people. Most of the violence of conquest involved imperial armies, though on occasion civilians too were caught up in the fighting and suffered terribly. In 634, for example, a battle between Byzantine and Arab forces in Palestine resulted in the death of some 4,000 villagers.

The motives driving the creation of the Arab Empire were broadly similar to those of other empires. The merchant leaders of the new Islamic community wanted to capture profitable trade routes and wealthy agricultural regions. Individual Arabs found in military expansion a route to wealth and social promotion. The need to harness the immense energies of the Arabian transformation was also important. The fragile unity of the umma threatened to come apart after Muhammad’s death, and external expansion provided a common task for the community.

While many among the new conquerors viewed the mission of empire in terms of jihad, bringing righteous government to the peoples they conquered, this did not mean imposing a new religion. In fact for the better part of a century after Muhammad’s death, his followers usually referred to themselves as “believers,” a term that appears in the Quran far more often than “Muslims” and one that included pious Jews and Christians as well as newly monotheistic Arabs. Such a posture eased the acceptance of the new political order, for many people recently incorporated in the emerging Arab Empire were already monotheists and familiar with the core ideas and practices of the Believers’ Movement—prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, revelation, and prophets. Furthermore, the new rulers were remarkably tolerant of established Jewish and Christian faiths. The first governor of Arab-ruled Jerusalem was a Jew. Many old Christian churches continued to operate and new ones were constructed. A Nestorian Christian patriarch in Iraq wrote to one of his bishops around 647 C.E. observing that the new rulers “not only do not fight Christianity, they even commend our religion, show honor to the priests and monasteries and saints of the Lord, and make gifts to the monasteries and churches.”8 Formal agreements or treaties recognized Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians as “people of the book,” giving them the status of dhimmis (dihm-mees), protected but second-class subjects. Such people were permitted to freely practice their own religion, so long as they paid a special tax known as the jizya. Theoretically the tax was a substitute for military service, supposedly forbidden to non-Muslims. In practice, many dhimmis served in the highest offices within Muslim kingdoms and in their armies as well.

In other ways too, the Arab rulers of an expanding empire sought to limit the disruptive impact of conquest. To prevent indiscriminate destruction and exploitation of conquered peoples, occupying Arab armies were restricted to garrison towns, segregated from the native population. Local elites and bureaucratic structures were incorporated into the new Arab Empire. Nonetheless, the empire worked many changes on its subjects, the most enduring of which was the mass conversion of Middle Eastern peoples to what became by the eighth century the new and separate religion of Islam.