The Messenger and the Message

Description

Question

What did the Quran expect from those who followed its teachings?

[Answer Question]

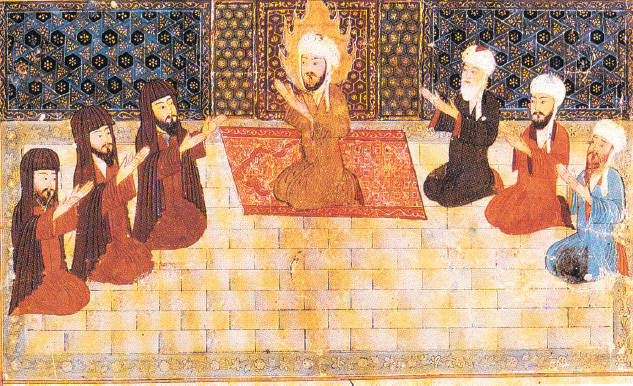

The catalyst for those events and for the birth of this new religion was a single individual, Muhammad Ibn Abdullah (570–632 C.E.), who was born in Mecca to a Quraysh family. As a young boy, Muhammad lost his parents, came under the care of an uncle, and worked as a shepherd to pay his keep. Later he became a trader and traveled as far north as Syria. At the age of twenty-five, he married a wealthy widow, Khadija, herself a prosperous merchant, with whom he fathered six children. A highly reflective man deeply troubled by the religious corruption and social inequalities of Mecca, he often undertook periods of withdrawal and meditation in the arid mountains outside the city. There, like the Buddha and Jesus, Muhammad had a powerful, overwhelming religious experience that left him convinced, albeit reluctantly, that he was Allah’s messenger to the Arabs, commissioned to bring to them a scripture in their own language. (See Visual Sources: The Life of the Prophet for images from the life of Muhammad.)

According to Muslim tradition, the revelations began in 610 and continued periodically over the next twenty-two years. Those revelations, recorded in the Quran, became the sacred scriptures of Islam, which to this day most Muslims regard as the very words of God and the core of their faith. Intended to be recited rather than simply read for information, the Quran, Muslims claim, when heard in its original Arabic, conveys nothing less than the very presence of the Divine. Its unmatched poetic beauty, miraculous to Muslims, convinced many that it was indeed a revelation from God. One of the earliest converts testified to its power: “When I heard the Quran, my heart was softened and I wept and Islam entered into me.”3 (See Document 9.1 for selections from the Quran.)

In its Arabian setting, the Quran’s message, delivered through Muhammad, was revolutionary. Religiously, it was radically monotheistic, presenting Allah as the only God, the all-powerful Creator, good, just, and merciful. Allah was the “Lord sustainer of the worlds, the Compassionate, the Caring, master of the day of reckoning” and known to human beings “on the farthest horizon and within their own selves.”4 Here was an exalted conception of Deity that drew heavily on traditions of Jewish and Christian monotheism. As “the Messenger of God,” Muhammad presented himself in the line of earlier prophets—Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and many others. He was the last, “the seal of the prophets,” bearing God’s final revelation to humankind. It was not so much a call to a new faith as an invitation to return to the old and pure religion of Abraham from which Jews, Christians, and Arabs alike had deviated. Jews had wrongly conceived of themselves as a uniquely “chosen people”; Christians had made their prophet into a god; and Arabs had become wildly polytheistic. To all of this, the message of the Quran was a corrective.

Submission to Allah (“Muslim” means “one who submits”) was the primary obligation of believers and the means of achieving a God-conscious life in this world and a place in paradise after death. According to the Quran, however, submission was not merely an individual or a spiritual act, for it involved the creation of a whole new society. Over and again, the Quran denounced the prevailing social practices of an increasingly prosperous Mecca: the hoarding of wealth, the exploitation of the poor, the charging of high rates of interest on loans, corrupt business deals, the abuse of women, and the neglect of widows and orphans. Like the Jewish prophets of the Old Testament, the Quran demanded social justice and laid out a prescription for its implementation. It sought a return to the older values of Arab tribal life—solidarity, equality, concern for the poor—which had been undermined, particularly in Mecca, by growing wealth and commercialism.

The message of the Quran challenged not only the ancient polytheism of Arab religion and the social injustices of Mecca but also the entire tribal and clan structure of Arab society, which was so prone to war, feuding, and violence. The just and moral society of Islam was the umma (UMH-mah), the community of all believers, replacing tribal, ethnic, or racial identities. Such a society would be a “witness over the nations,” for according to the Quran, “You are the best community evolved for mankind, enjoining what is right and forbidding what is wrong.”5 In this community, women too had an honored and spiritually equal place. “The believers, men and women, are protectors of one another,” declared the Quran.6 The umma, then, was to be a new and just community, bound by a common belief rather than by territory, language, or tribe.

The core message of the Quran—the remembrance of God—was effectively summarized as a set of five requirements for believers, known as the Pillars of Islam. The first pillar expressed the heart of the Islamic message: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.” The second pillar was ritual prayer, performed five times a day. Accompanying practices, including cleansing, bowing, kneeling, and prostration, expressed believers’ submission to Allah and provided a frequent reminder, amid the busyness of daily life, that they were living in the presence of God. The third pillar, almsgiving, reflected the Quran’s repeated demands for social justice by requiring believers to give generously to support the poor and needy of the community. The fourth pillar established a month of fasting during Ramadan, which meant abstaining from food, drink, and sexual relations from the first light of dawn to sundown. It provided an occasion for self-purification and a reminder of the needs of the hungry. The fifth pillar encouraged a pilgrimage to Mecca, known as the hajj (HAHJ), during which believers from all over the Islamic world assembled once a year and put on identical simple white clothing as they reenacted key events in Islamic history. For at least the few days of the hajj, the many worlds of Islam must surely have seemed a single realm.

A further requirement for believers, sometimes called the sixth pillar, was “struggle,” or jihad in Arabic. Its more general meaning, which Muhammad referred to as the “greater jihad,” was an interior personal effort of each believer against greed and selfishness, a spiritual striving toward living a God-conscious life. In its “lesser” form, the “jihad of the sword,” the Quran authorized armed struggle against the forces of unbelief and evil as a means of establishing Muslim rule and of defending the umma from the threats of infidel aggressors. The understanding and use of the jihad concept has varied widely over the many centuries of Islamic history and remains a matter of much controversy among Muslims in the twenty-first century.