The Big Picture

Since World War I: A New Period in World History?

Dividing up time into coherent segments—periods, eras, ages—is the way historians mark major changes in the lives of individuals, local communities, social groups, nations, and civilizations and also in the larger story of humankind as a whole. Because all such divisions are artificial, imposed by scholars on a continuously flowing stream of events, they are endlessly controversial and never more so than in the case of the twentieth century. To many historians, that century, and a new era in the human journey, began in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I. That terrible conflict, after all, represented a fratricidal civil war within Western civilization, triggered the Russian Revolution and the beginning of world communism, and stimulated many in the colonial world to work for their own independence. And the way it ended set the stage for an even more terrible struggle in World War II.

But does the century since 1914 represent a separate phase of world history? Granting it that status has become conventional in many world history textbooks, including this one, but there are reasons to wonder whether future generations will agree. One problem, of course, lies in the brevity of this period—only 100 years, compared to the many centuries or millennia that comprise earlier eras. It is interesting to notice that our time periods get progressively shorter as we approach the present. Perhaps this is because an immense overload of information about the most recent century makes it difficult to distinguish what will prove of lasting significance and what will later seem of only passing importance. Furthermore, because we are so close to the events we study and obviously ignorant of the future, we cannot know if or when this most recent period of world history will end. Or, as some have argued, has it ended already, perhaps with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, with the attacks of September 11, 2001, or with the global economic crisis beginning in 2008? If so, are we now in yet another phase of historical development?

Like all other historical periods, this most recent century both carried on from the past and developed distinctive characteristics as well. Whether that combination of the old and new merits the designation of a separate era in world history will likely be debated for a long time to come. For our purposes, it will be enough to highlight both its continuities with the past and the sharp changes that the last 100 years have witnessed.

Consider, for example, the world wars that played such an important role in the first half of the century. Featured in Chapter 20, they grew out of Europeans’ persistent inability to embody their civilization within a single state or empire, as China had long done. They also represent a further stage of European rivalries around the globe that had been going on for four centuries. Nonetheless, the world wars of the twentieth century were also new in the extent to which whole populations were mobilized to fight them and in the enormity of the destruction that they caused. During World War II, for example, Hitler’s attempted extermination of the Jews in the Holocaust and the United States’ dropping of atomic bombs on Japanese cities marked something new in the history of human conflict.

The communist phenomenon, examined in Chapter 21, provides another illustration of the blending of old and new. The Russian (1917) and Chinese (1949) revolutions, both of which were enormous social upheavals, brought to power regimes committed to remaking their societies from top to bottom along socialist lines. They were the first large-scale attempts in modern world history to undertake such a gigantic task, and in doing so they broke sharply with the capitalist democratic model of the West. They also created a new and global division of humankind, expressed most dramatically in the cold war between the communist East and the capitalist West. On the other hand, the communist experience also drew much from the past. The great revolutions of the twentieth century derived from long-standing conflicts within Russian and Chinese societies, particularly between impoverished and exploited peasants and dominant landlord classes. The ideology of those communist governments came from the thinking of the nineteenth-century German intellectual Karl Marx. Their intentions, like those of their capitalist enemies, were modernization and industrialization. They simply claimed to do it better—more rapidly and more justly.

Another distinguishing feature of the twentieth century lay in the disintegration of its great empires—the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian/Soviet empires and especially the European empires that had encompassed so much of Asia and Africa. In their wake, dozens of new nation-states emerged, fundamentally reshaping the world of this most recent century. Examined in Chapter 22, this enormous process is at one level, simply the latest turn of the wheel in the endless rise and fall of empires, dating back to the ancient Assyrians. But something new occurred this time, for the very idea of empire was rendered illegitimate in the twentieth century, much as slavery lost its international acceptance in the nineteenth century. The superpowers of the mid-twentieth century—the Soviet Union and the United States—both claimed an anticolonial ideology, even as both of them constructed their own “empires” of a different kind. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, some 200 nation-states, many of them in the Global South and each claiming sovereignty and legal equality with all the others, provided a distinctly new political order for the planet.

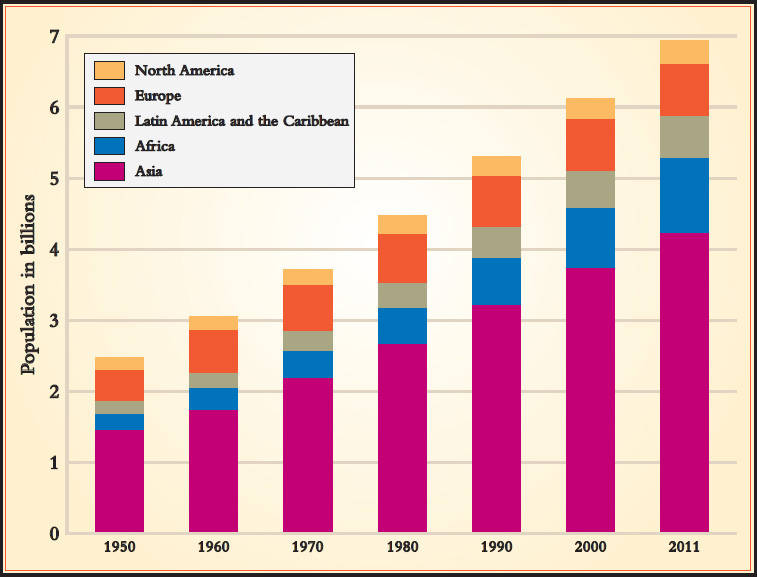

The less visible underlying processes of the twentieth century, just like the more dramatic wars, revolutions, and political upheavals, also had roots in the past as well as new expressions in the new century. Feminism, for example, explored in Chapter 23, had taken root in the West during the nineteenth century but became global in the twentieth, challenging women’s subordination more extensively than ever before. Perhaps the most fundamental process of the past century has been explosive population growth, as human numbers more than quadrupled since 1900, leaving the planet with about 7 billion people by 2011. This was an absolutely unprecedented rate of growth that conditioned practically every other feature of the century’s history. Still, this new element of twentieth-century world history built on earlier achievements, most notably the increased food supply deriving from the global spread of American crops such as corn and potatoes. Improvements in medicine and sanitation, which grew out of the earlier Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, likewise drove down death rates and thus spurred population growth.

Snapshot World Population Growth, 1950–2011

The great bulk of the world’s population growth in the second half of the twentieth century occurred in the developing countries of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

While global population increased fourfold in the twentieth century, industrial output grew fortyfold. Despite large variations over time and place, this unprecedented economic growth was associated with a cascading rate of scientific and technological innovation as well as with the extension of industrial production to many regions of the world. This too was a wholly novel feature of twentieth-century world history and, combined with population growth, resulted in an extraordinary and mounting human impact on the environment. Historian J. R. McNeill wrote that “this is the first time in human history that we have altered ecosystems with such intensity, on such a scale, and with such speed. . . . The human race, without intending anything of the sort, has undertaken a gigantic uncontrolled experiment on the earth.”1 By the late twentieth century, that experiment had taken humankind well into what many scientists have been calling the Anthropocene era, the age of man, in which human activity is leaving an enduring and global mark on the geological, atmospheric, and biological history of the planet itself. From a longer-term perspective, of course, these developments represent a continued unfolding of the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. Both began in Europe, but in the twentieth century they largely lost their unique association with the West as they took hold in many cultures. Furthermore, the human impact on the earth and other living creatures has a history dating back to the extinction of some large mammals at the hands of Paleolithic hunters, although the scope and extent of that impact during the past century is without precedent.

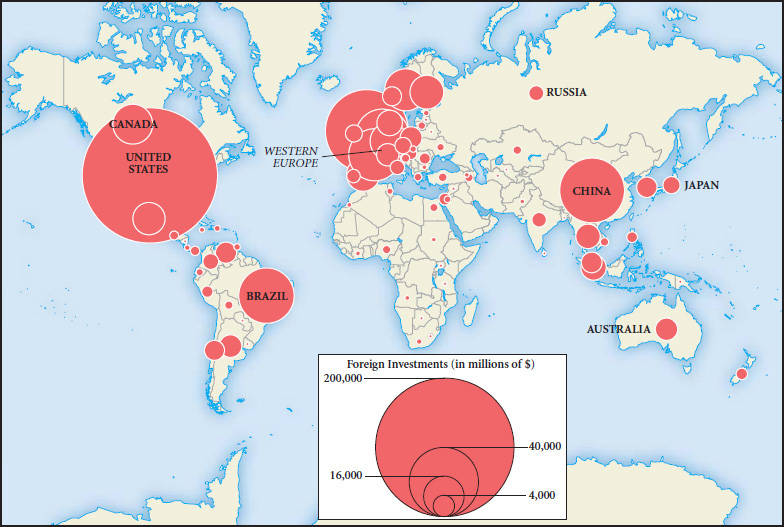

Much the same might be said about that other grand process of contemporary world history—globalization, which is the focus of Chapter 23. It too has a genealogy reaching deep into the past, reflected in the Silk Road trading network; Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan commerce; the spread of Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam; and the Columbian exchange. But the most recent century deepened and extended the connections among the distinct peoples, nations, and regions of the world in ways unparalleled in earlier times. A few strokes on a keyboard can send money racing around the planet; radio, television, and the Internet link the world in an unprecedented network of communication; far more people than ever before produce for and depend on the world market; and global inequalities increasingly surface as sources of international conflict. For good or ill, we live—all of us—in a new phase of an ancient process.

The four chapters of Part Six explore these global themes that have so decisively shaped the history of the past century. Perhaps there is enough that is new about that century to treat it, tentatively, as a distinct era in human history, but only what happens next will determine how this period will be understood by later generations. Will it be regarded as the beginning of the end of the modern age, as human demands on the earth prove unsustainable? Or will it be seen as the midpoint of an ongoing process that extends a full modernity to the entire planet? Will recognition of our common fate as human beings generate shared values, a culture of tolerance, and an easing of international tensions? Or will global inequalities and rivalry over diminishing resources foster even greater and more dangerous conflicts? Like all of our ancestors, every one of them, we too live in a fog when contemplating our futures and see more clearly only in retrospect. In this strange way, our future will shape the telling of the past, even as the past shapes the living of the future.