Colonies of Sugar

Another and quite different kind of colonial society emerged in the lowland areas of Brazil, ruled by Portugal, and in the Spanish, British, French, and Dutch colonies in the Caribbean. These regions lacked the great civilizations of Mexico and Peru. Nor did they provide much mineral wealth until the Brazilian gold rush of the 1690s and the discovery of diamonds a little later. Still, Europeans found a very profitable substitute in sugar, which was much in demand in Europe, where it was used as a medicine, a spice, a sweetener, a preservative, and in sculptured forms as a decoration that indicated high status. Although commercial agriculture in the Spanish Empire served a domestic market in its towns and mining camps, these sugar-

Comparison

How did the plantation societies of Brazil and the Caribbean differ from those of southern colonies in British North America?

Large-

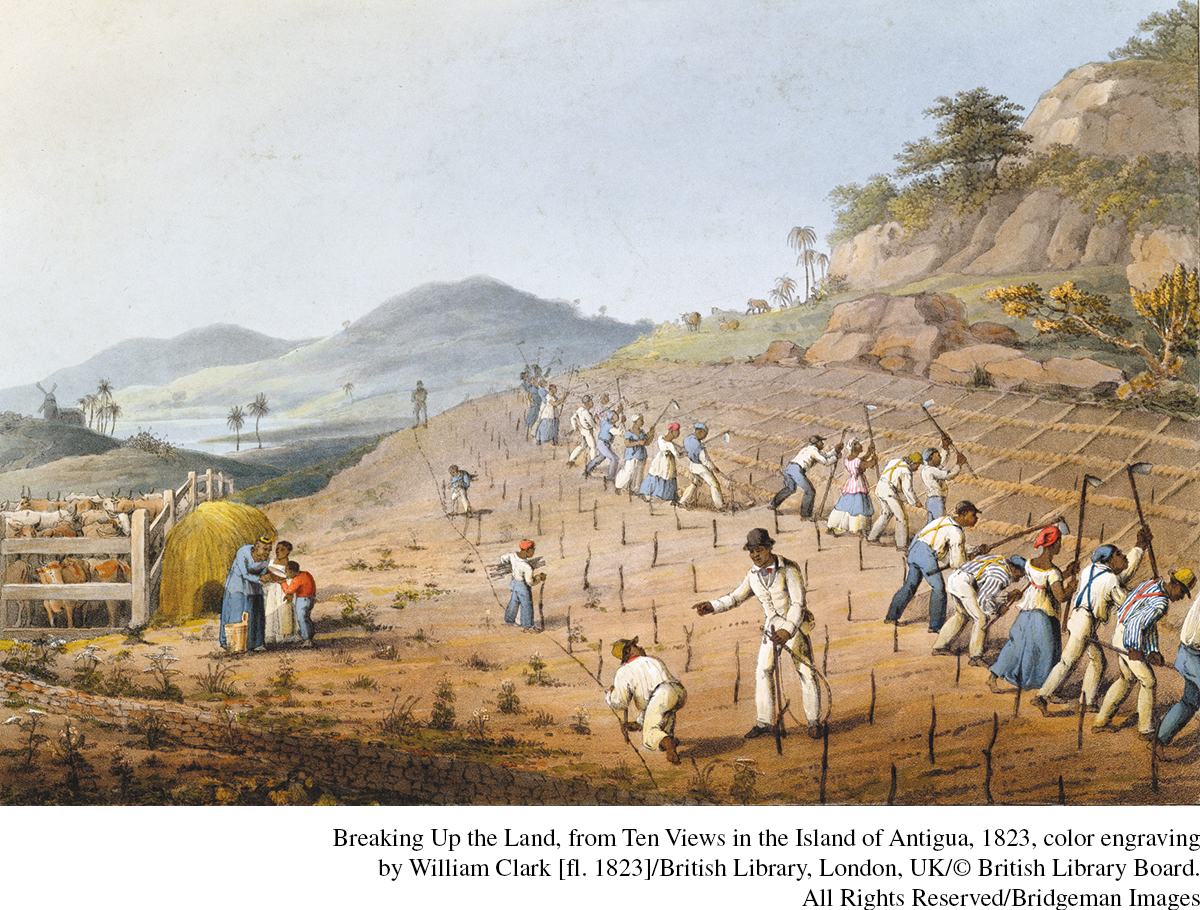

Sugar decisively transformed Brazil and the Caribbean. Its production, which involved both growing the sugarcane and processing it into usable sugar, was very labor-

Slaves worked on sugar-

More male slaves than female slaves were imported from Africa into the sugar economies of the Americas, leading to major and persistent gender imbalances. Nonetheless, female slaves did play distinctive roles in these societies. Women made up about half of the field gangs that did the heavy work of planting and harvesting sugarcane. They were subject to the same brutal punishments and received the same rations as their male counterparts, though they were seldom permitted to undertake the more skilled labor inside the sugar mills. Women who worked in urban areas, mostly for white female owners, did domestic chores and were often hired out as laborers in various homes, shops, laundries, inns, and brothels. Discouraged from establishing stable families, women had to endure, often alone, the wrenching separation from their children that occurred when they were sold. Mary Prince, a Caribbean slave who wrote a brief account of her life, recalled the pain of families torn apart: “The great God above alone knows the thoughts of the poor slave’s heart, and the bitter pains which follow such separations as these. All that we love taken away from us—

The extensive use of African slave labor gave these plantation colonies a very different ethnic and racial makeup than that of highland Spanish America, as the Snapshot indicates. Thus, after three centuries of colonial rule, a substantial majority of Brazil’s population was either partially or wholly of African descent. In the French Caribbean colony of Haiti in 1790, the corresponding figure was 93 percent.

As in Spanish America, a considerable amount of racial mixing took place in Brazil. Cross-

The plantation complex of the Americas, based on African slavery, extended beyond the Caribbean and Brazil to encompass the southern colonies of British North America, where tobacco, cotton, rice, and indigo were major crops, but the social outcomes of these plantation colonies were quite different from those farther south. Because European women had joined the colonial migration to North America at an early date, these colonies experienced less racial mixing and certainly demonstrated less willingness to recognize the offspring of such unions and accord them a place in society. A sharply defined racial system (with black Africans, “red” Native Americans, and white Europeans) evolved in North America, whereas both Portuguese and Spanish colonies acknowledged a wide variety of mixed-

SNAPSHOT: Ethnic Composition of Colonial Societies in Latin America (1825)18

| Highland Spanish America | Portuguese America (Brazil) | |

| Europeans | 18.2 percent | 23.4 percent |

| Mixed- |

28.3 percent | 17.8 percent |

| Africans | 11.9 percent | 49.8 percent |

| Native Americans | 41.7 percent | 9.1 percent |

Slavery too was different in North America than in the sugar colonies. By 1750 or so, slaves in what became the United States proved able to reproduce themselves, and by the time of the Civil War almost all North American slaves had been born in the New World. That was never the case in Latin America, where large-

Does this mean, then, that racism was absent in colonial Brazil? Certainly not, but it was different from racism in North America. For one thing, in North America, any African ancestry, no matter how small or distant, made a person “black”; in Brazil, a person of African and non-