ZOOMING IN: Devshirme: The “Gathering” of Christian Boys in the Ottoman Empire

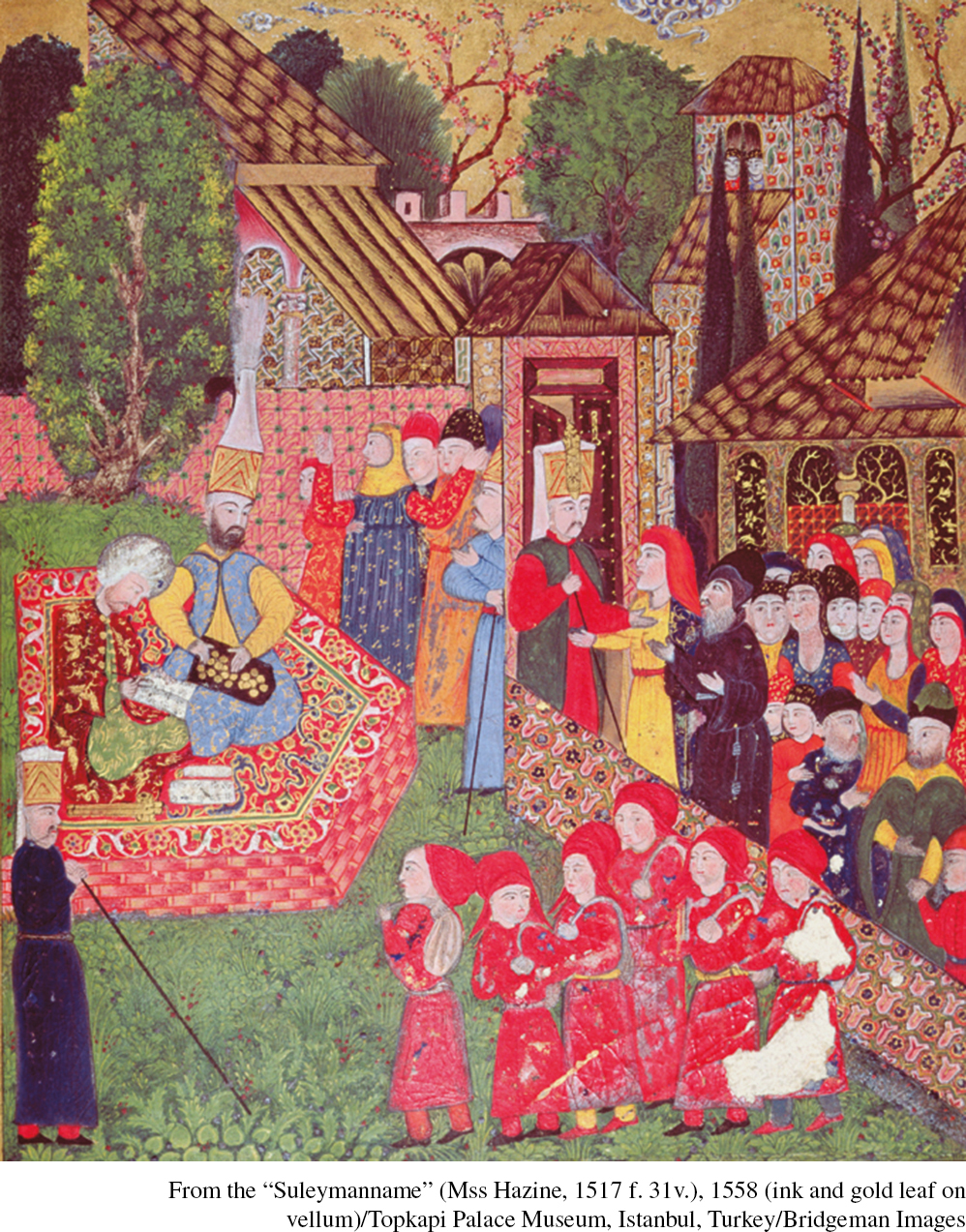

Every few years, Ottoman official recruiters descended on rural Christian villages in the Balkan provinces of the empire, mostly among Serbs, Greeks, and Albanians. There they required the village priest to present the birth records of the village and to assemble boys of about ten to eighteen years of age. Then they selected a certain number of these boys, dressed them in red uniforms, and marched them off to Constantinople. Once the boys arrived, they were circumcised, converted to Islam, given a Muslim name, and enrolled in a long training program to prepare them for administrative or military positions within the Ottoman government.

This was the devshirme, or “gathering,” of Christian boys, a distinctive practice that began in the mid-

Technically, the devshirme recruits were slaves, but they were quite different from ordinary purchased slaves. They were absorbed into Ottoman society in distinctive and privileged roles, and some of them were able to rise to very prominent positions, including that of grand vizier, the chief adviser to the sultan himself. One such official recalled that he was taken “weeping and in distress,” but also reported with some pride that “a shepherd may be [transported] to a sultan’s domain.”34 So prestigious were such positions—

Yet there is little doubt that the devshirme system brought great suffering to the empire’s Christian subjects and was widely hated and resisted. In 1395, an Eastern Orthodox metropolitan, or archbishop, named Isidore Glabas from Thessaloniki in Greece delivered a scathing public sermon denouncing the practice, no doubt reflecting the views of his parishioners. “My eyes are filled with tears and can no longer bear to see my beloved ones,” he began. Then he outlined the various ways that the devshirme brought grief to his people: their children were “forced to change over to alien customs and to become a vessel of barbaric garb, speech, impiety, and other contaminations, all in a moment.” His words reflected the Greeks’ view of Turks as “barbarians” and their fear that their children might be subjected to castration as eunuchs or exposed to the homosexuality widely regarded as a part of Janissary life. Furthermore, according to the archbishop, the devshirme threatened the continuity of family life, for a father “will not have his son to send him to his grave in fitting manner.” And who, he asked, would not “lament his son because a free child becomes a slave?” Worst of all, in the archbishop’s view, was the danger to the immortal soul of a Christian boy who was circumcised and converted to Islam, for “he is shamefully separated from God and has become miserably entangled with the devil, and in the end will be sent to darkness and hell with the demons.”36

It was no wonder then that Ottoman Christians deployed many strategies to avoid the devshirme. Some communities required their boys to formally marry at a very young age; parish priests might conveniently lose names from the parish registries; families sometimes fled to avoid the recruiters; Eastern Orthodox Christians on occasion appealed to the pope or to Catholic military orders for help, “lest we lose our children.” On several occasions, villagers murdered the recruiters and many times sought to bribe them.

By the mid-

Questions: How might you summarize the origins and outcomes of the devshirme system? How does this practice alter your understanding of slavery?