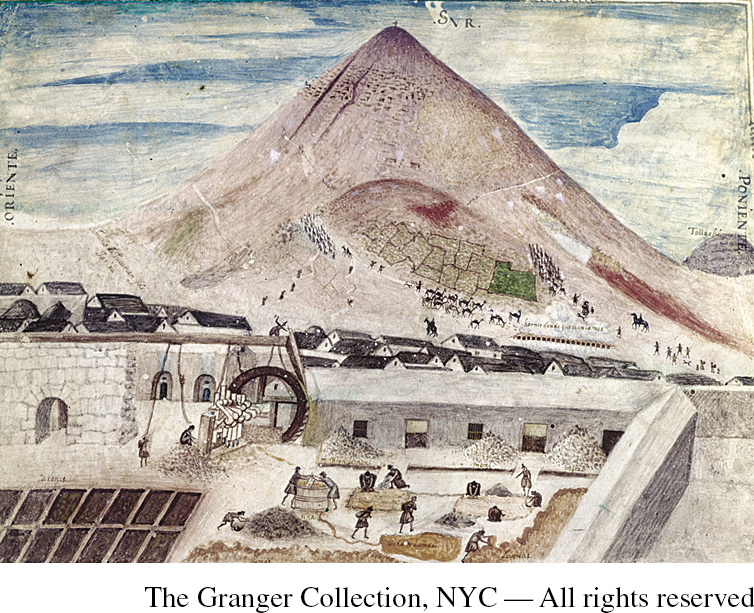

ZOOMING IN: Potosí, a Mountain of Silver

China’s insatiable demand for silver during the early modern period drove global commerce, transforming the economies and societies of far distant lands. Perhaps nowhere did the silver trade have a greater impact than at Cerro de Potosí, a mountain located in a barren and remote stretch of Andean highlands, ten weeks’ travel by mule from Lima, Peru. In 1545, Spanish prospectors discovered the richest deposit of silver in history at Potosí, and within a few decades this single mountain was producing over half of the silver mined in the world each year. At its foot, the city of Potosí grew rapidly. “New people arrive by the hour, attracted by the smell of silver,” commented a Spanish observer in the 1570s. Within just a few decades, Potosí’s population had reached 160,000 people, making it the largest city in the Americas and equivalent in size to London, Amsterdam, or Seville.

The silver was mined and processed at great human and environmental cost. The Spanish authorities forced Native American villages across a wide region of the Andes to supply workers for the mines, with as many as 14,000 to 16,000 at a time laboring in horrendous conditions. A Spanish priest observed, “Once inside, they spend the whole week in there without emerging, working with tallow candles. They are in great danger inside there, for one very small stone that falls injures or kills anyone it strikes. If 20 healthy Indians enter on Monday, half may emerge crippled on Saturday.”15 Work aboveground, often undertaken by slaves of African descent, was also dangerous because extracting silver from the mined ore required mixing it with the toxic metal mercury. Many thousands died. Mortality rates were so high that some families held funeral services for men drafted to work in the mines before they embarked for Potosí. Beyond the human cost, the environment suffered as well when highly intensive mining techniques deforested the region and poisoned and eroded the soil.

Although some indigenous merchants, muleteers, and chiefs were enriched by mining, much of the wealth generated flowed to the Europeans who owned the mines and to the Spanish government, which impounded one-

While the mines caused much suffering, the silver-

But the silver that created Potosí also caused its decline. After a century of intensive mining, all that remained were lower-

Question: What can Potosí tell us about the consequences of global trade in the early modern period?