Science as Cultural Revolution

Before the Scientific Revolution, educated Europeans held a view of the world that derived from Aristotle, perhaps the greatest of the ancient Greek philosophers, and from Ptolemy, a Greco-

Change

What was revolutionary about the Scientific Revolution?

The initial breakthrough in the Scientific Revolution came from the Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, whose famous book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres was published in the year of his death, 1543. Its essential argument was that “at the middle of all things lies the sun” and that the earth, like the other planets, revolved around it. Thus the earth was no longer unique or at the obvious center of God’s attention.

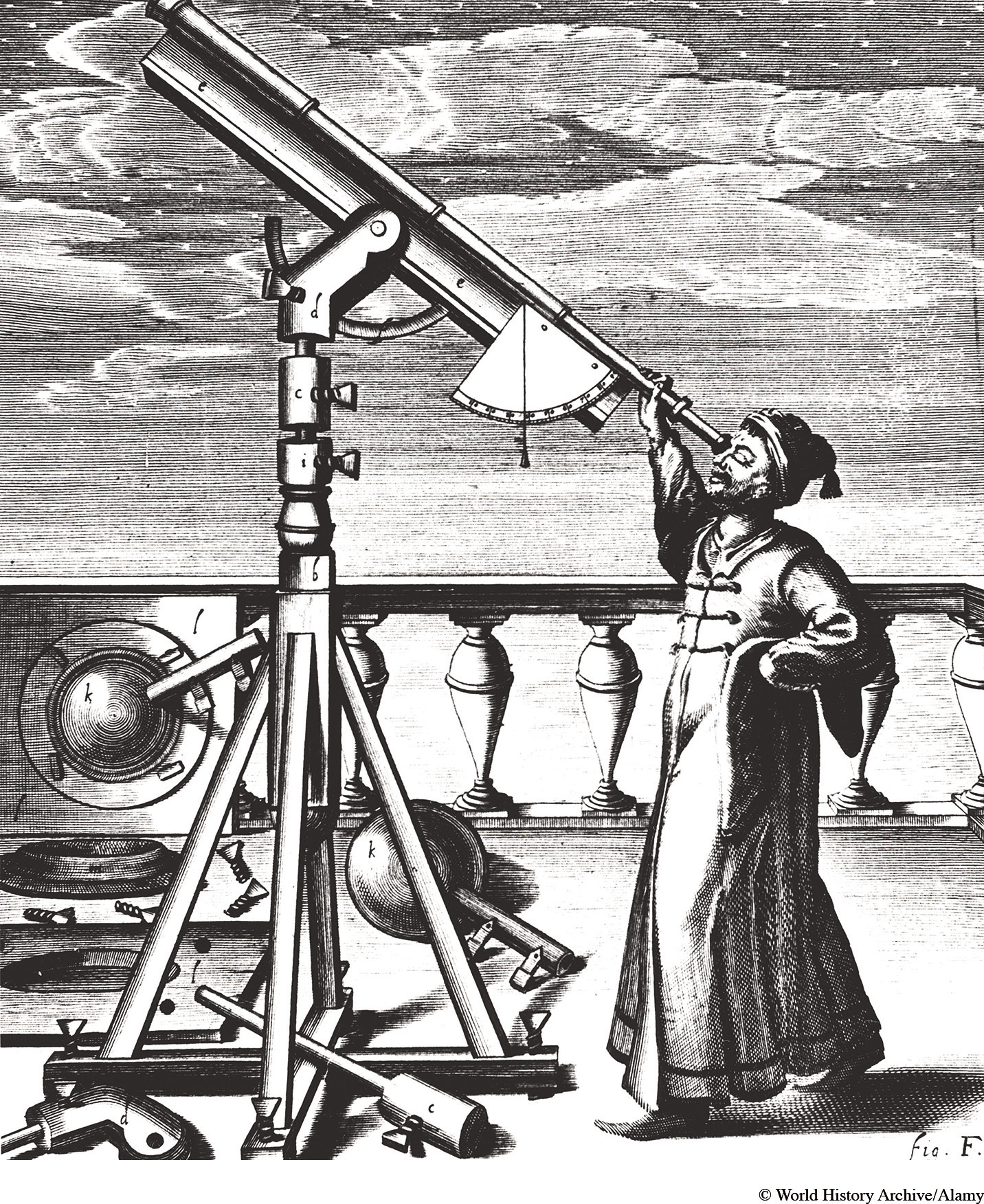

Other European scientists built on Copernicus’s central insight, and some even argued that other inhabited worlds and other kinds of humans existed. Less speculatively, in the early seventeenth century Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician, showed that the planets followed elliptical orbits, undermining the ancient belief that they moved in perfect circles. The Italian Galileo (gal-

The culmination of the Scientific Revolution came in the work of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–

By the time Newton died, a revolutionary new understanding of the physical universe had emerged among educated Europeans: the universe was no longer propelled by supernatural forces but functioned on its own according to scientific principles that could be described mathematically. Articulating this view, Kepler wrote, “The machine of the universe is not similar to a divine animated being but similar to a clock.”20 Furthermore, it was a machine that regulated itself, requiring neither God nor angels to account for its normal operation. Knowledge of that universe could be obtained through human reason alone—

Like the physical universe, the human body also lost some of its mystery. The careful dissections of cadavers and animals enabled doctors and scientists to describe the human body with much greater accuracy and to understand the circulation of the blood throughout the body. The heart was no longer the mysterious center of the body’s heat and the seat of its passions; instead it was just another machine, a complex muscle that functioned as a pump.

The movers and shakers of this enormous cultural transformation were almost entirely male. European women, after all, had been largely excluded from the universities where much of the new science was discussed. A few aristocratic women, however, had the leisure and connections to participate informally in the scientific networks of their male relatives. Through her marriage to the Duke of Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish (1623–

Much of this scientific thinking developed in the face of strenuous opposition from the Catholic Church, for both its teachings and its authority were under attack. The Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, proclaiming an infinite universe and many worlds, was burned at the stake in 1600, and Galileo was compelled by the Church to publicly renounce his belief that the earth moved around an orbit and rotated on its axis.

But scholars have sometimes exaggerated the conflict of science and religion, casting it in military terms as an almost unbroken war. None of the early scientists rejected Christianity. Copernicus in fact published his famous book with the support of several leading Catholic churchmen and dedicated it to the pope. After all, several earlier Catholic writers had proposed the idea of the earth in motion. He more likely feared the criticism of fellow scientists than that of the church hierarchy. Galileo himself proclaimed the compatibility of science and faith, and his lack of diplomacy in dealing with church leaders was at least in part responsible for his quarrel with the Church.25 Newton was a serious biblical scholar and saw no inherent contradiction between his ideas and belief in God. “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets,” he declared, “could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent Being.”26 Thus the Church gradually accommodated as well as resisted the new ideas, largely by compartmentalizing them. Science might prevail in its limited sphere of describing the physical universe, but religion was still the arbiter of truth about those ultimate questions concerning human salvation, righteous behavior, and the larger purposes of life.