ZOOMING IN: Galileo and the Telescope: Reflecting on Science and Religion

The Scientific Revolution was predicated on the idea that knowledge of how the universe worked was acquired through a combination of careful observations, controlled experiments, and the formulation of general laws, expressed in mathematical terms. New scientific instruments capable of making precise empirical observations underpinned some of the most important breakthroughs of the period. Perhaps no single invention produced more dramatic discoveries than the telescope, the first of which were produced in the early seventeenth century by Dutch eyeglass makers.

The impact of new instruments depended on how scientists employed them. In the case of the telescope, it was the brilliant Italian mathematician and astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–

Galileo’s empirical evidence transformed the debate over the nature of the cosmos. His dramatic and unexpected discoveries were readily grasped, and with the aid of a telescope anyone could confirm their veracity. His initial findings were heralded by many in the scientific community, including Christoph Clavius, the Church’s leading astronomer in Rome. Galileo’s findings led him to conclude that Copernicus (1473–

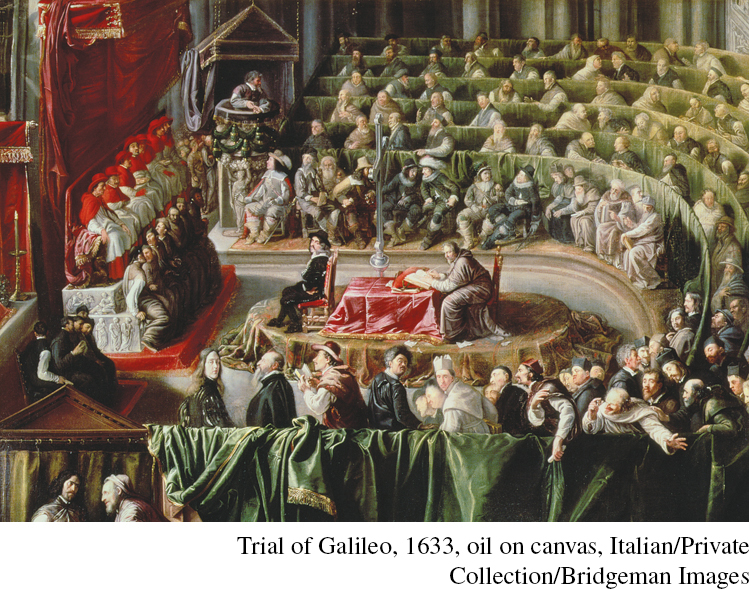

When the Church condemned Copernicus’s theory in 1616, it remained silent on Galileo’s astronomical observations, instead warning him to refrain from teaching or promoting Copernicus’s ideas. Ultimately, though, Galileo came into conflict with church authorities when in 1629 he published, with what he thought was the consent of the Church, the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, a work sympathetic to Copernicus’s sun-

Although Galileo was formally convicted of disobeying the Church’s order to remain silent on the issue of Copernicus’s theory, the question most fundamentally at stake in the trial was “What does it mean, ‘to know something’?”21 This question of the relationship between scientific knowledge, primarily concerned with how the universe works, and other forms of “knowledge,” derived from divine revelation or mystical experience, has persisted in the West. Over 350 years after the trial, Pope John Paul II spoke of Galileo’s conviction in a public speech in 1992, declaring it a “sad misunderstanding” that belongs to the past, but one with ongoing resonance because “the underlying problems of this case concern both the nature of science and the message of faith.” Addressing the central question of what it means to know something, the pope declared scientific and religious knowledge to be compatible: “There exist two realms of knowledge, one which has its source in Revelation and one which reason can discover by its own power…. The distinction between the two realms of knowledge ought not to be understood as opposition…. The methodologies proper to each make it possible to bring out different aspects of reality.”22

Strangely enough, Galileo himself had expressed something similar centuries earlier. “Nor is God,” he wrote, “any less excellently revealed in Nature’s actions than in the sacred statements of the Bible.”23 Finding the place of new scientific knowledge in a constellation of older wisdom traditions proved a fraught but highly significant development in the emergence of the modern world.

Question: What can Galileo’s discoveries with his telescope and his conviction by the Inquisition tell us about the Scientific Revolution?