ZOOMING IN: The English Luddites and Machine Breaking

If you do Not Cause those Dressing Machines to be Remov’d Within the Bounds of Seven Days … your factory and all that it Contains Will and Shall Surely Be Set on fire … it is Not our Desire to Do you the Least Injury, But We are fully Determin’d to Destroy Both Dressing Machines and Steam Looms.28

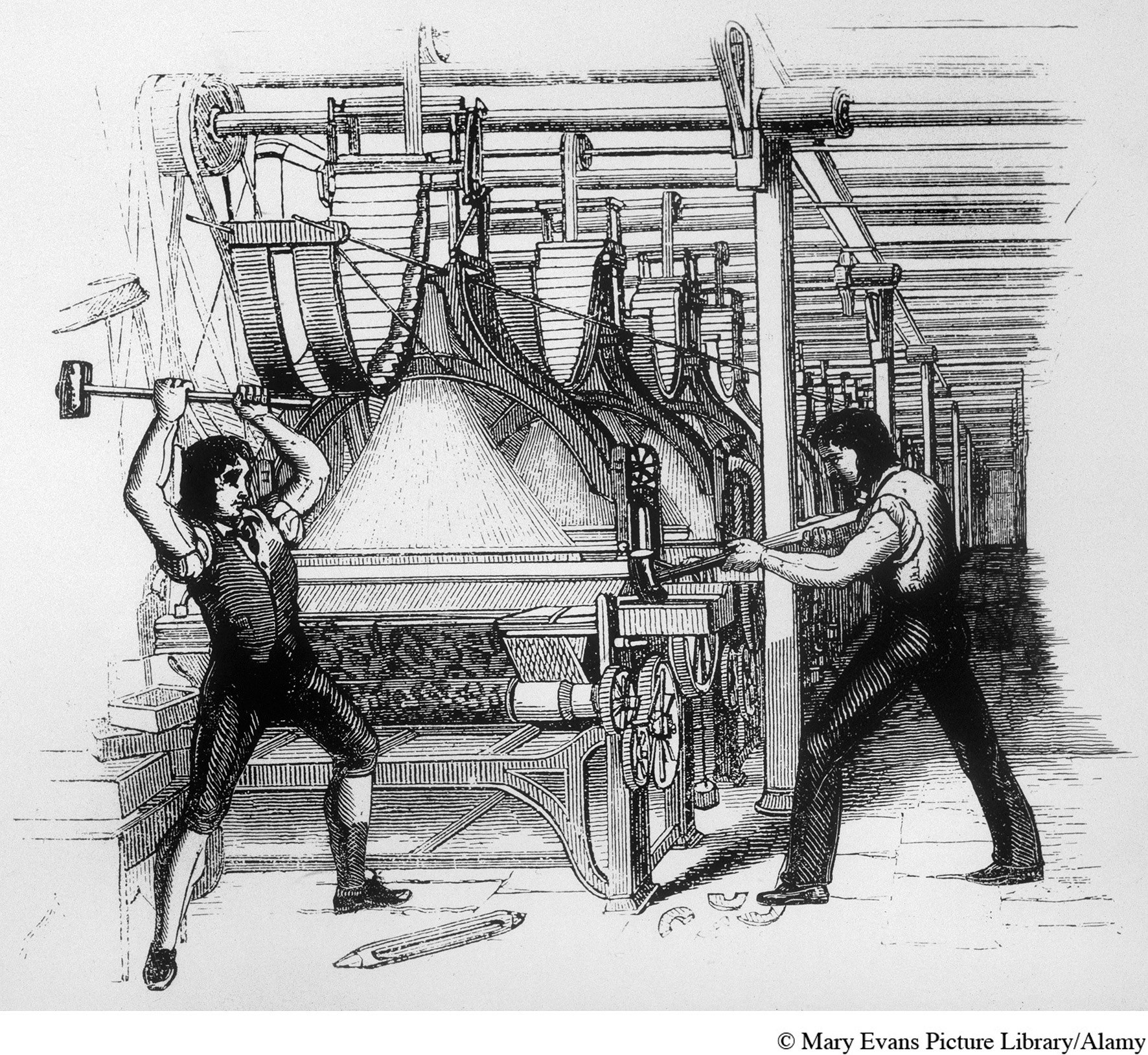

Between 1811 and 1813, this kind of warning was sent to hundreds of English workshops in the woolen and cotton industry, where more efficient machines, some of them steam powered, threatened the jobs and livelihood of workers. Over and over, that threat was carried out as well-

So widespread and serious was this Luddite uprising that the British government sent 12,000 troops to suppress it, more than it was then devoting to the struggle against Napoleon in continental Europe. And a new law, rushed through Parliament as an “emergency measure” in 1812, made those who destroyed mechanized looms subject to the death penalty. Some sixty to seventy alleged Luddites were in fact hanged, and sometimes beheaded as well, for machine breaking.

In the governing circles of England, Luddism was widely regarded as blind protest, an outrageous, unthinking, and futile resistance to progress. It has remained in more recent times a term of insult applied to those who resist or reject technological innovation. And yet, a closer look suggests that we might view that movement with some sympathy as an understandable response to a painful transformation of social life when few alternatives for expressing grievances were available.

At the time of the Luddite uprising, England was involved in an increasingly unpopular war with Napoleon’s France, and mutual blockades substantially reduced trade and hurt the textile industry. The country was also in the early phase of an Industrial Revolution in which mechanized production was replacing skilled artisan labor. All of this, plus some bad weather and poor harvests, combined to generate real economic hardship, unemployment, and hunger. Bread riots and various protests against high prices proliferated.

Furthermore, English elites were embracing new laissez-

At one level, the Luddite machine-

And yet in other ways, the rebels anticipated the future with their demands for minimum wage and an end to child labor, their concern about inferior-

After 1813, the organized Luddite movement faded away. But it serves as a cautionary reminder that what is hailed as progress claims victims as well as beneficiaries.

Questions: To what extent did the concerns of the Luddites come to pass as the Industrial Revolution unfolded? How does your understanding of the Luddites affect your posture toward technological change in our time?